Cattle producers might raise their eyebrows at the thought of spending money this coming year to improve their pastures, especially after dealing with the effects of BSE.

However, with producers holding more cattle on their farms and with improved moisture conditions, rejuvenating pastures to gain greater production could make sense, says Glenn Friesen, provincial forage specialist for Manitoba Agriculture.

During the Manitoba Grazing School in Brandon earlier this month, Friesen covered the gamut of options available to producers. Those ranged from better grazing management through to fertilization, sod seeding and brush control.

Read Also

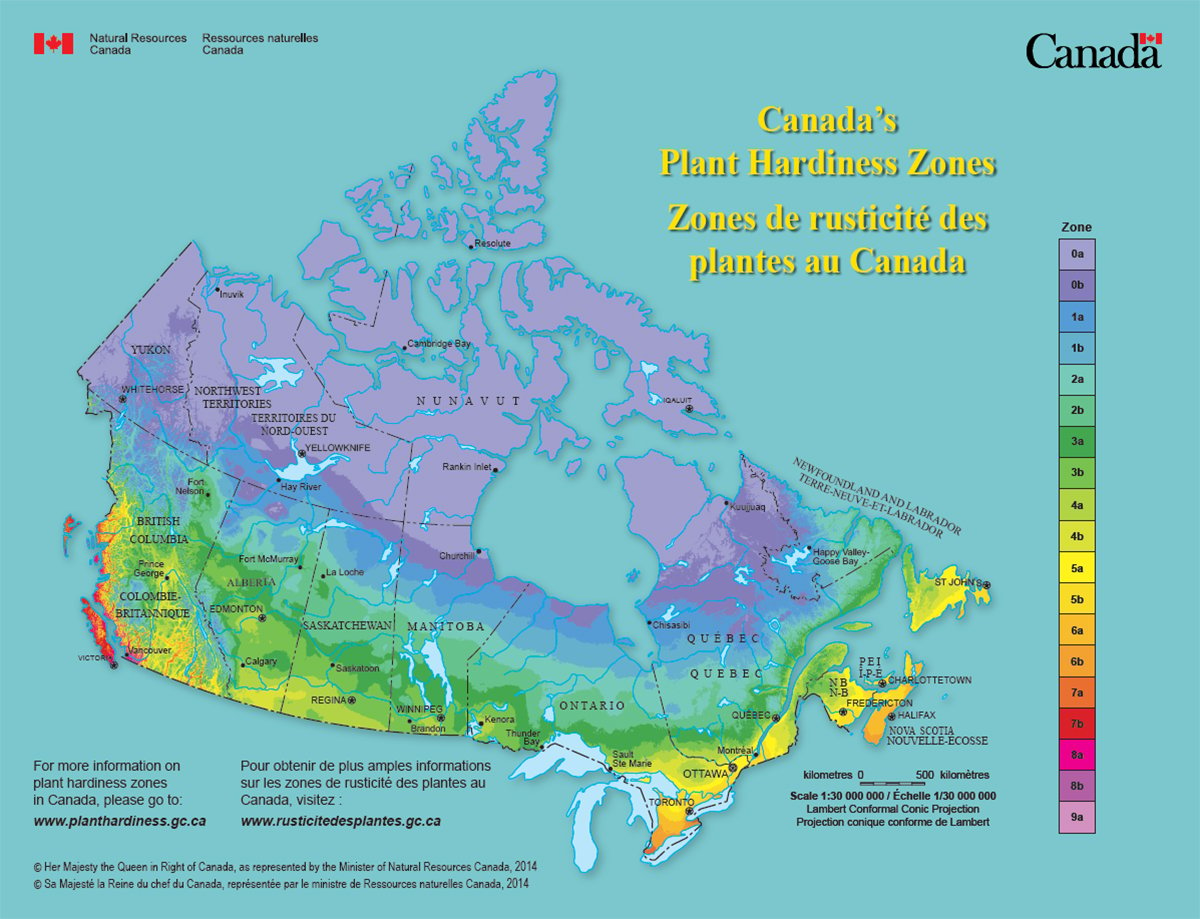

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Some of the possibilities, such as rotational grazing instead of continuous grazing, have had a lot of attention in the past decade. However, a topic that hasn’t caught much attention in the farm press is fertilization, particularly when it comes to putting new life into tired grass pastures.

Improved grazing systems generally give producers the biggest bang for the buck, according to Friesen, but fertilization could be worth some thought. That’s especially the case if one considers that the nutrients in grass pastures in Manitoba have gradually been depleted to the point where many are deficient in important nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

When cattle eat grass, a portion of the nutrients is returned to the pasture in the form of manure and urine, but another portion is converted into beef.

“Over a period of time, the amount of nutrients removed can be quite significant,” Friesen said. “Over the years, you’ve removed so much nitrogen that you’re deficient in it.”

A survey of pasture fertility in Manitoba in 1999 found that almost all were deficient in nitrogen and more than half were deficient in phosphorus, both critical for plant growth.

The question then is what to do about it.

While improved grazing management will probably provide a better return on the dollar over the long term, not everyone has the time to do that. Fertilization, as Friesen puts it, is “a quick and dirty way” to improve pasture performance.

“The grazing treatments always pay off more in yield than the fertilizer.”

Soil tests are the first step.

Friesen recommended taking at least one soil sample for every 10 acres. On pastures where there is a lot of rolling terrain, sample from the mid-slope area rather than from the top of knolls or from low-lying land.

Although it’s preferable to have all the nutrients at optimum levels, Friesen suggested focusing on the main nutrients supporting plant growth and healthy root development.

“If you really had a tight pocketbook and you didn’t want to spend a lot of money, I would say the two most important are nitrogen and phosphorus.”

Manure already is a common option for helping to replenish nutrients on pasture. When it comes to commercial fertilizer, broadcasting urea is one of the better options for Manitoba, Friesen said. Ammonium nitrate, which is less prone to losses through volatilization, could be another, although supplies are limited in the province, he said.

A typical cost range to apply commercial fertilizer is $20-$50 per acre, including the cost of fertilizer and its application. By comparison, changing the grazing system, which usually means erecting fences, has a lower cost at $10-$20, and the increased yields from a good grazing system tend to endure longer.

A spring application of fertilizer is best, since there usually is adequate moisture to get the nutrients to the plants.

In areas where it is dry during the summer, a split application likely isn’t a good option. That might fit better in regions such as southeastern Manitoba, where summer rainfall is more common.

Most of the fertilizer likely will be taken up in the first year if there is adequate moisture in the soil and decent root health in the pasture. On the other hand, fertilizer uptake could be limited in that first year if conditions are dry or if roots were in poor condition as a result of overgrazing in previous years.

Phosphorus supports a healthy rooting system. That enables plants to reach farther into the soil to tap moisture and nutrients that were already there, but beyond reach previously.

“Better roots essentially mean more grass,” Friesen said. “This (commercial fertilizer) is sort of a quick fix but you’ll have to keep doing it unless you change your grazing system. Changing grazing systems is a longer term fix for root health than fertilizer.”

A soil test of the pasture a year or two after fertilizing helps gauge how much it has addressed a serious nutrient deficiency.

Friesen offered some general rules to consider about pasture fertilizer. Bear in mind that numbers will vary depending on factors such as the kinds of grasses in the pasture, their stage of growth and how well the cattle convert feed, not to mention the age and size of cattle.

- It takes 10 pounds of forage to produce one lb. of beef.

- Those 10 lb. of forage will contain, on average, 0.2 lb. of protein, assuming it’s a forage with 12 percent crude protein.

- Assuming the grazing season is 120 days long, and the cattle are consuming the forage at a rate of three percent of their body mass per day, it will take 64 lb. of nitrogen to produce the forage needed by one animal during that season.

- Since an average of 70 percent of the nitrogen consumed by cattle while grazing is returned to the pasture as manure and urine, there still would be 20 lb. of nitrogen removed per animal per year through grazing. An exception would be if an animal died and the decomposition of its bones and flesh allowed at least a portion of that N to be returned to the soil.

By comparison, 70-80 percent of the phosphorus consumed by cattle grazing a grass pasture will be returned to the soil and 75-85 percent of the potassium typically is returned.

Although nitrogen and phosphorus are important nutrients, Friesen said deficiencies in other nutrients, such as potassium, may need attention as well.

For example, if pasture grasses appear to have a hard time withstanding winters, it could be sign of a potassium deficiency. Again, a soil test would reveal the situation.

When talking about tired pastures, Friesen was referring to the ones that either were never broken for grain and hay production or were broken and returned to pasture decades ago.

People often assume that older grass pastures in Manitoba are populated with native grasses, but that often isn’t the case, he said. In pastures weakened through overgrazing, native species often were edged out by the encroachment of Kentucky bluegrass or smooth brome.

Those grasses are not native and although they can be good forage producers earlier in the growing season, their production will taper off going into the warmer summer months.

Choosing to improve grazing practices rather than fertilizing often results in the return of native species to a pasture, said Friesen. The odds that native species will return to a tired pasture are poorer if a producer chooses only to fertilize.