The end of 2024 can only mean one thing: our annual look at big weather stories from across Canada, with a definite bias toward western Canadian stories. These are based on Environment Canada’s list of the top 10 weather stories of 2024.

First has to be the wildfires in and around Jasper and the weather that led up to that event. With insured losses from the fire reaching $880 million, this was the second costliest wildfire disaster in Canadian history, only surpassed by the $4.8 billion Fort McMurray fire in 2016.

After a cooler than average June, temperatures soared in July across Jasper National Park, with temperatures peaking at 38 C on July 21. Along with the heat, there was little rainfall, which created tinder dry conditions. Lightning from a thunderstorm complex, which moved through the region early on July 22, set off two forest fires that quickly grew.

Read Also

Russian wheat exports start to pick up the pace

Russia has had a slow start for its 2025-26 wheat export program, but the pace is starting to pick up and that is a bearish factor for prices.

By that evening, much of the region was under an evacuation order and within two days the fire, propelled by strong winds, was at the town of Jasper’s border.

Many of us followed what happened next on the news or social media. I was camping on Lake Superior as this unfolded and struggled to find news and wondered if anything would be left of the town. As with most forest fires, it moved rapidly through the town while fire fighters, equipped with special breathing apparatus, did their best to save critical infrastructure.

It was a near-impossible task. The fire was so powerful that it created its own weather. Thunderstorms and winds were powerful enough to throw shipping containers over 100 metres.

When all was said and done, 358 of the town’s 1,113 structures where either damaged or destroyed. It wasn’t until Sept. 7 that the fire was declared under control.

Next up, in my opinion, is the hailstorm that hit Calgary and became the costliest hailstorm in Canada’s history and the second most costly weather disaster behind the Fort McMurray fire.

The final tally from this storm was an astronomical $2.8 billion. The storm formed early in the evening of June 13 along the foothills and moved toward the Calgary region. Two main storms cells developed. The northern-most cell tracked across the northern half of Calgary.

While this region is known as Canada’s hail alley, this storm set itself apart from all others. Hailstones the size of chicken eggs were reported and it just wasn’t the size, but the quantity. It looked as if a winter storm had moved through. In fact, the impact of this storm was visible from space as it tore through Calgary and agricultural land to the east.

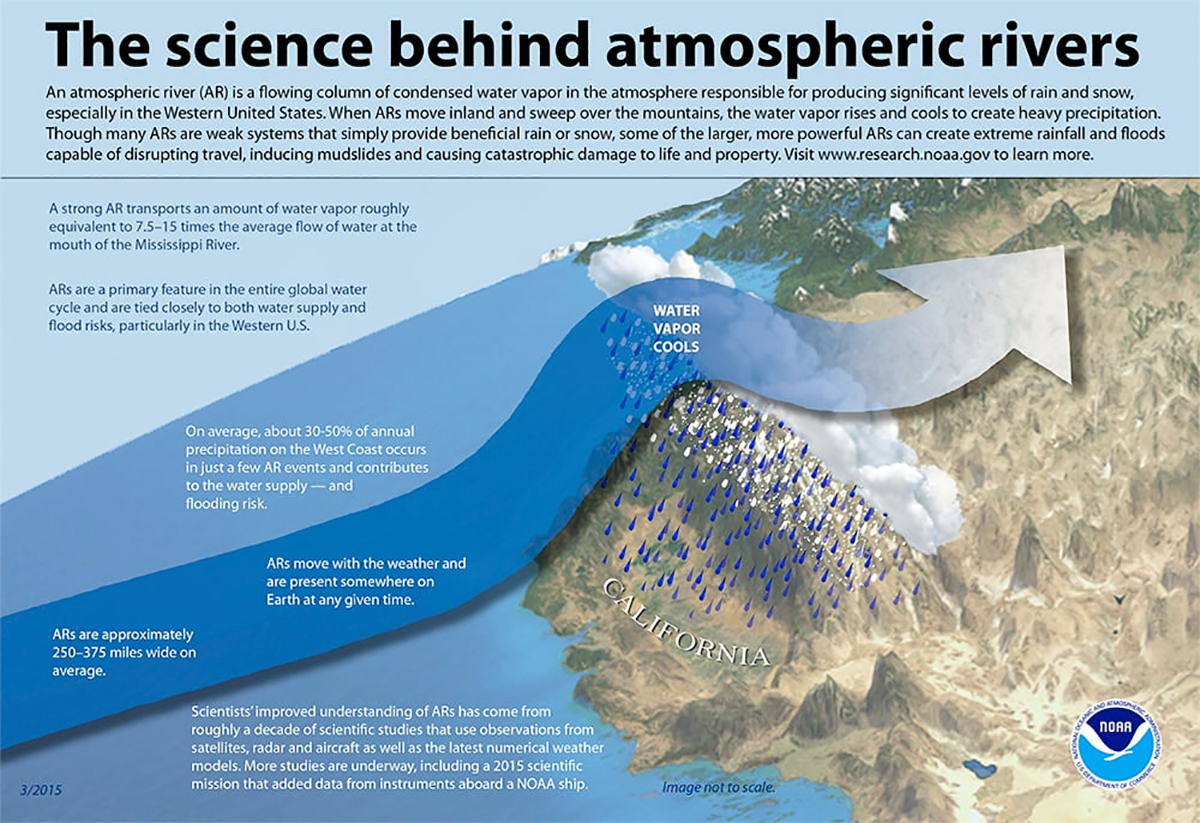

Third on my list of Environment Canada’s top 10 is the double whammy of atmospheric rivers that hit British Columbia. An atmospheric river is a relatively long and narrow flow in the atmosphere, like a river, that transports high quantities of water vapour from tropical regions to other parts of the world.

The amount of water carried by these atmospheric rivers varies, but on average they transport the same amount of water that typically flows out of the Mississippi River at its mouth. Really strong atmospheric rivers can be several times this amount.

Needless to say, they can bring a lot of moisture to a region. While two specific atmospheric rivers brought flooding rains to B.C., these events are not unusual. Typically, 30 to 40 rivers hit B.C. every year, bringing a large portion of the region’s rain and snow.

The first major atmospheric river hit in late January, bringing several rounds of heavy rain. Higher elevations reported more than 200 millimetres, bringing widespread flooding. The tropical origin of this moisture will also bring in warm air, which often makes things worse. This air raises the snow line and rain falls on snowpacks, which promotes melting that contributes to more runoff.

An interesting byproduct of this was near record-breaking warm temperatures across the Prairies. The warm, moist air rose over the mountains, then condensed and fell as rain. This warm air continued eastward, bringing temperatures as warm as the upper teens to southern Alberta. Saskatchewan saw highs in early February in the 4 to 8 C range and Manitoba had a stretch of eight days with above freezing temperatures.

The second major atmospheric river hit this region on Oct. 18 to 20. This river was particularly wet. I quote Environment Canada: “Daily rainfall records fell across the region, with many weather stations around Metro Vancouver recording over 100 mm on the Sunday, Oct. 20 alone.

“By the weekend’s end, West Vancouver had received 203 mm, while Coquitlam recorded a staggering 256 mm. But it was Kennedy Lake on Vancouver Island that recorded the highest multi-day total, with a soggy 318 mm.”

To put this into perspective, average yearly precipitation across the Prairies is 350 to 550 mm. While this atmospheric river caused plenty of damage, truly tragic was the loss of five lives.

Last on the list is the brutally cold snap that hit a large portion of B.C., Alberta and parts of Saskatchewan last winter. The heart of the cold weather was in Alberta, where Edmonton, as an example, had six days in a row where overnight lows fell below -40 C, with the coldest temperature coming in at -46.6 C.

According to Environment Canada, between Jan. 11 and 15, more than 60 daily minimum temperature records were broken across British Columbia. Alberta broke about 125 daily minimum temperature records, including eight all-time cold records between Jan. 10 and 17. Saskatchewan broke nearly 25 daily minimum records and one all-time cold record.

While the coldest absolute temperatures were recorded in Alberta, temperatures across central B.C. also plunged to some of the coldest ever recorded. With temperatures in Kelowna dropping to around -30 C, most of the fruit trees didn’t stand a chance. The cold snap resulted in failures or near failures in most stone fruits and grape crops.

The cold also resulted in extreme pressure on power grids across Alberta and B.C. where daily power consumption records where recorded. In Alberta, warnings were issued to conserve power to avoid rotating power outages.

It makes one wonder what Mother Nature has in store for us in 2025.

Daniel Bezte is a teacher by profession with a BA in geography, specializing in climatology, from the University of Winnipeg. He operates a computerized weather station near Birds Hill Park, Man. Contact him at dmgbezte@gmail.com.