Glacier FarmMedia – It’s about 6,700 kilometres from a farm near Wilcox, Sask., to Canada House on London’s historic Trafalgar Square.

But the road that took a long-serving Canadian politician from that village, population 322, to heading Canada’s second-largest diplomatic mission is even longer.

Related story: Goodale brings ag trade experience to British posting

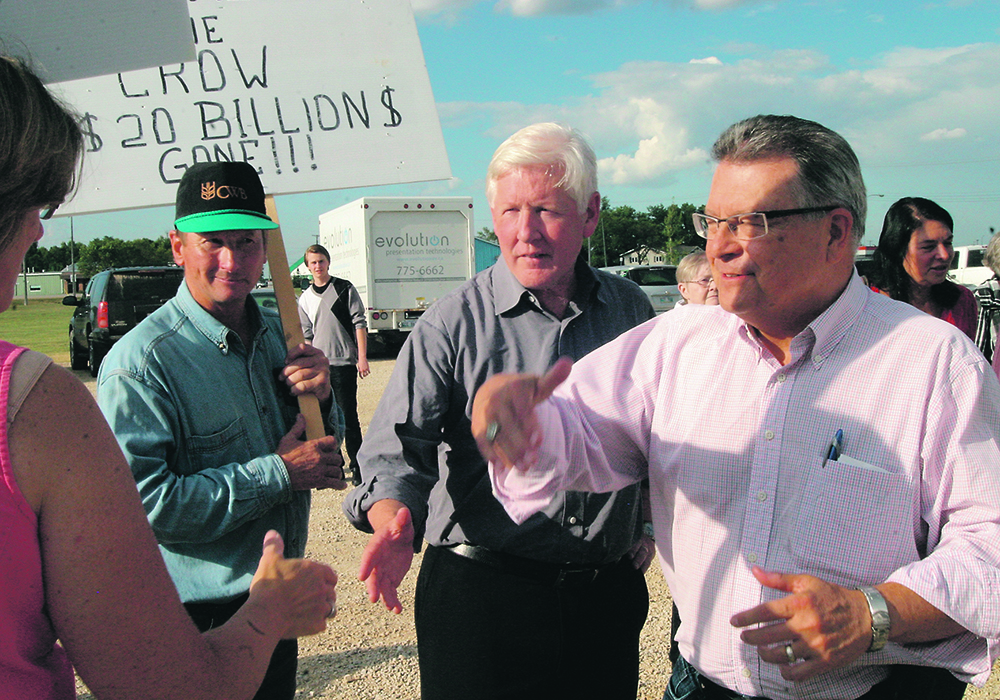

Ralph Goodale is a familiar name to Prairie farmers. He served as member of Parliament for Saskatchewan’s Wascana riding, which includes part of Regina, for 26 years, from 1993 to 2019. Before that, he was MP for the now-defunct riding of Assiniboia from 1974 to 1979, then served as leader of the Saskatchewan Liberal Party from 1981 to 1988.

He has held numerous cabinet posts, including a stint as federal agriculture minister from 1993 to 1997 and minister responsible for the Canadian Wheat Board.

Despite the enmity that many Prairie farmers feel toward the federal Liberal party, they lost one of their most effective advocates in Ottawa when Goodale lost the 2019 election, says one Liberal Party insider.

David Herle is a fellow Saskatchewanian, long-time Liberal, former senior adviser to former Prime Minister Paul Martin, a pollster and host of the Herle Burly and Curse of Politics podcasts.

“I think there’d be a pretty strong consensus on all sides of the House (of Commons) that his defeat in 2019 was a real loss for Saskatchewan, a real loss for the Government of Canada, real loss for farmers because no matter what portfolio he had, he was always representing farmers,” Herle says.

Goodale has fond memories of his career in politics. It had its ups and downs, but ultimately he says he enjoyed his time as an elected representative and the work he did in government and opposition.

“When you think about the whole extent of the experience, it’s been a very positive thing, and I have been privileged to be part of it,” says Goodale.

Asked about location of the farm where he grew up, he has a ready and proud answer.

“Five miles east of Ruby’s Diner,” he says.

That’s the fictional restaurant in the folksy and popular TV sitcom Corner Gas, still on the air in reruns, and set in the nonexistent town of Dog River. In real life, the filming location was Rouleau.

“The grid road that runs out of Rouleau heading toward No. 6 highway goes right by the farm,” Goodale, 74, says in a video chat from his Canada House office last November.

He isn’t sure when he realized he wouldn’t be a farmer. But then again, high commissioner to the United Kingdom never occurred to him either. Perhaps innate curiousity played a role in his journey from Wilcox to London via Ottawa.

“I was really interested in radio and television and broadcasting,” as a youth, Goodale says. “I was interested in the law, interested in medicine.”

As a university student, he worked for CBC Radio.

The 1960s were turbulent. Goodale, who turned 18 in Canada’s centennial year of 1967, recalls the political stalemate between federal party leaders John Diefenbaker and Lester Pearson, and the Kennedy and King assassinations and controversial Vietnam War in the United States.

“All of those things tended to make that generation of the 1960s quite a political generation,” Goodale says. “I was interested in the political process, watched a lot of it on television, read about it in the newspapers and so on. I really didn’t have any early thoughts that I would go into politics myself, but I did have the feeling that that’s a process in which I would like to be involved.

“Now, that didn’t rule out also being involved in agriculture, but … there were … competing streams of interest…”

At the age when Goodale might have taken over the farm, interest rates of more than 20 per cent made it “a practical impossibility,” he says. “And I don’t think in that era I was alone.”

In 1971, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree with Great Distinction from the University of Saskatchewan, followed a year later with Bachelor of Laws degree with Distinction. He earned the Brown Prize as the leading graduate in his class.

Initially, politics was an academic interest.

“It never occurred to me in those days that I would actually get involved. Just really by coincidence, I met people who were involved in political activity.”

One early influence was his local MLA, Cy MacDonald, who invited Goodale to his first political meeting. In fall 1967, Goodale started university and took part in his first election campaign to re-elect MacDonald.

“One thing leads to another … and suddenly the involvement was all consuming. It’s something that I had not intended to do, but ended up doing and really enjoyed every minute of it.”

Another Saskatchewan Liberal, MP Otto Lang, was one of Goodale’s mentors. Lang, a lawyer known for his sharp mind and intellect, served as federal minister of transport and minister responsible for the wheat board. Goodale worked for Lang in Ottawa before running, with Lang’s encouragement, in the 1974 federal election.

“Otto was just so hardworking and so thoughtful and so progressive in his thinking,” Goodale says. “He was always about five moves ahead.”

Herle says Goodale is a lot like Lang.

“Otto was unquestionably his political hero when I met Ralph,” Herle says. “What people of course don’t know about Ralph is that he’s got an incredibly fine legal mind. If he’d not gone into politics, he could easily have been one of Canada’s most accomplished lawyers.”

In the 2011 election, Stephen Harper won a majority, reducing the Liberals to a record low number of seats, but Goodale was reelected.

“In that election there are 14 federal ridings in Saskatchewan,” Herle says. “Half of all of the votes that were cast for the Liberal party in Saskatchewan were cast for Ralph Goodale.

“He is a candidate that people have wanted to vote for despite the fact that he’s been with an incredibly unpopular political party his whole life. He’s been dragging the Liberal party around on his back his whole life. If he’d been in another party, my God …”

In 2006, Goodale was selected by his House of Commons peers as Canada’s first-ever Parliamentarian of the Year, sponsored in part by Maclean’s magazine.

“He perfectly represents the values that we wish to honour with this award …” Macleans wrote of Goodale. “He has earned a long list of admirers on both sides of the House, largely because of the personal integrity he has brought to the job …”

Based on an Ipsos survey for Maclean’s, Goodale won top marks from fellow MPs for being the hardest working, best orator and most knowledgeable.

Herle describes two budgets Goodale tabled as finance minister as “exceptional,” including the one in 2005.

“They fall within the fiscal constraints of the time, but they fund all kinds of innovative ideas,” Herle says. “Elizabeth May (of the Green Party) will tell you to this day that if the 2005 budget had been implemented, we would be hitting our (carbon) emissions targets. Elizabeth May says the 2005 budget is the most substantial climate plan ever presented by a government in Canada.”

It wasn’t all clear sailing. In November 2005, Goodale announced that income trusts would not be subjected to new taxes. But just before that, some speculators earned quick profits investing in trusts, raising the spectre of a leak. That sparked an RCMP investigation half way through the December-January election campaign.

“It was a body blow, the lowest moment in his career,” Maclean’s reported. “Prime Minister Paul Martin stuck by him, and (Conservative opposition leader) Stephen Harper pointedly avoided questioning Goodale’s personal culpability, casting the blame more broadly on Liberals.”

“Challenging Ralph Goodale’s credibility was a losing strategy,” Liberal MP Bill Graham told the magazine.

The Liberals lost and Harper’s Conservative Party of Canada formed a minority government. Goodale was re-elected and eventually vindicated in the investigation, which resulted in charges against an official in the finance department who later pled guilty.

“I was re-elected in Wascana with one of the largest margins I’ve ever had,” Goodale says. “The RCMP investigated it for 15 months and then concluded that there was absolutely no basis upon which to sustain any allegations.

“The conclusion was that there was in fact no wrong-doing on my part or on the part of any political actors.”

These days Goodale is putting his political prowess to work representing Canada in the United Kingdom, which he deems “a great honour.”

“It’s like being able to play on your national team.”

Lots has happened since Goodale took the job, including the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, her death, her state funeral and King Charles’ coronation. The U.K. is also on its third prime minister, Rishi Sunak, following the resignations of Liz Truss and Boris Johnson.

“We’re working on these two trade deals that involve an intensive level of activity,” Goodale says. “We’ve had to deal with the war in Ukraine and now the war in the Middle East. It’s been just an incredible period of very dynamic activity and sometimes kinetic activity.”

Presumably a diplomat will be, well, diplomatic. How long a leash has Ottawa given him?

“I have not seen a leash. I make the points that I think need to be made. I try to keep my former colleagues in government well informed so nobody is taken by surprise. Nobody so far has come to me and said, ‘you said what?’ So far, so good.”

A positive attitude helps too, says Goodale, whether it’s in the hurly-burly of electoral politics or tense trade negotiations. An attitude of fairness and respect is required.

“I think that makes a huge difference. If you go into a confrontational situation expecting the worst … no question, it’ll be messy. But if you go in with a positive attitude … assuming the other side is going to be decent and fair minded too, then you can actually have a fairly positive demeanour.”

One of Goodale’s most famous former political staffers is Jason Kenney, Alberta’s former premier and a former high-profile Harper government cabinet minister. Kenney attended Notre Dame College, a private Catholic school in Wilcox, and worked one summer for Goodale when he was a member of the Saskatchewan Legislative Assembly.

“He was a bright young kid,” says Goodale. “He was clever. He, at that stage, I don’t think was necessarily destined for a political career. In fact, after he worked for me, he went off to study at a Jesuit school in San Francisco, so many people thought he was headed to a career in the priesthood. But that didn’t materialize and he got drawn into politics.

“But you could tell he had much of the skill set to do well. And he obviously did very well for a great many years.”

Now and again there was speculation that Goodale might run to lead the Liberal Party of Canada.

“But it’s something that I never really aspired to be,” he says. “I was very happy playing the roles I was given.

“Those were all roles that were very fulfilling. I got to work with a lot of terrific colleagues … on both sides of the House. There are great people elected in all parties that try to do their very best for their constituents and their country.”

Politics has always been a tough gig, but the hyper-partisan, winner-take-all ethos is making it tougher. Goodale understands why people are put off by politics.

“It’s not very pretty but we can’t give up on it. Democracy is just too important. And just imagine what those people are fighting for in Ukraine.

“We need to do a lot of things to improve the quality and the character of our political process and our democratic systems, but they are fundamental to what we stand for in the world and we can never give up on them.”