After a couple of July heat waves, the Prairies have seen a bit of a cool down.

Although a heat wave is a weather event, its impact on people is key. This is why we can have heat waves in winter, but they don’t get as much attention due to their more limited impact on people.

I looked around to see if there was an agricultural definition of a heat wave but didn’t find anything specific. The impact of a heat wave on agriculture depends on pre-existing conditions and the type of agricultural involved.

Read Also

Huge Black Sea flax crop to provide stiff competition

Russia and Kazakhstan harvested huge flax crops and will be providing stiff competition in China and the EU.

If you check Environment Canada’s website for a list of criteria for public weather alerts, you will find the following heat-related alerts for the Prairie provinces.

In southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, a heat warning or advisory is issued when two or more consecutive daytime maximum temperatures are expected to reach 32 C or warmer, and nighttime minimum temperatures are expected to remain at or above 16 C. An alert can also be issued when two or more consecutive days of humidex values are expected to reach 38 C or higher.

In southern Alberta it is the same criteria as southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, but without the mention of humidex values because this region rarely sees high humidity.

We now know the criteria, but what conditions come together to give as a heat wave?

To get the long-lasting, intense, record-breaking heat waves, a couple of meteorological events must come together. We usually need a blocking pattern, and the most typical pattern is the Omega block. It has upper-level lows sitting to our west and east, with a ridge of high pressure in the middle.

This is important because this pattern can become fairly stable and sit in one place for days. So far this year, we have not seen any strong blocking patterns develop.

The ridge of high pressure allows for a couple of things to happen. First, the descending air inhibits growth of clouds, which means plenty of sunshine, and in summer, sunshine means heat. On their own, sunny skies do not mean a heat wave. We see plenty of sunny days in a row without experiencing a heat wave.

The next part involves the strength of the high. When the high is strong, we get very strong subsidence (or sinking) of air. As this air is pushed downward, it hits the ground and is compressed, which heats it.

So, when there is a strong ridge of high pressure over us, the compression of sinking air can dramatically heat the air and give us some truly warm days. If the upper high is not that warm, then all this compressing and heating of the air won’t do much to give us record-breaking temperatures.

If the upper high is warm to begin with, then this compression of air, combined with the additional heating of the sun, can really push up the temperatures.

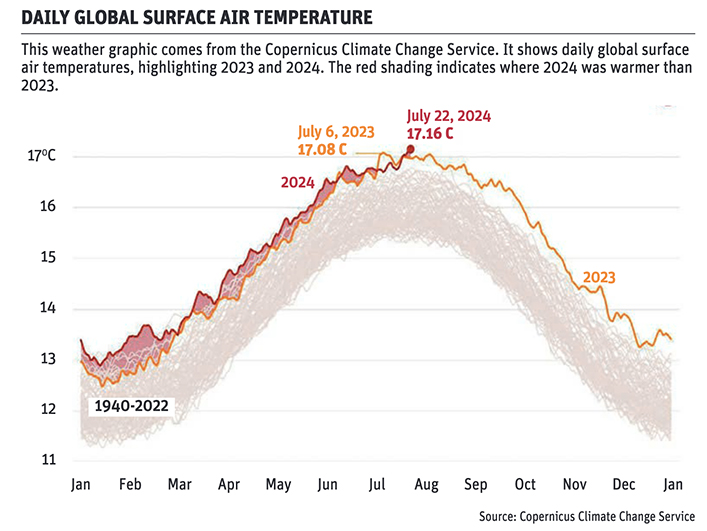

Add to this a steadily warming planet and the chance for extreme heat waves goes up. For example, while the July heat wave was not that extreme, the conditions that brought it were not favourable to the types of temperatures we saw.

Looking at the latest mid-range forecasts, there are signs of a building heat wave around the middle of August. That is a long way off and plenty can and will happen between now and then.

Daniel Bezte is a teacher by profession with a BA in geography, specializing in climatology, from the University of Winnipeg. He operates a computerized weather station near Birds Hill Park, Man. Contact him at dmgbezte@gmail.com.