Prairie vegetable growers are finding it difficult to control damage by root maggots using registered pesticides or accepted production practices, says Doug Waterer, a vegetable crops specialist with the department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan.

Waterer has attempted to develop an integrated control strategy using innovative chemical and cultural control methods.

“Although we found some hints as to future directions in research, we didn’t find any shining answer to control this insect pest,” said Waterer.

“Our research did demonstrate the depth of the problem, however. In fact, we confirmed reports that it is worse than previously suspected.”

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

He also confirmed that many recommended chemicals are not effective.

Waterer said root maggots attack the root system of a range of crops, including canola and vegetables such as cabbage, radish and rutabaga.

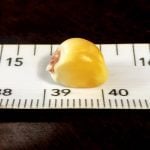

He used rutabagas as his test crop because they are highly susceptible to maggot damage throughout the cropping cycle.

“In trials conducted from 1994 to 1997, the impact of cultivar growth habit, planting date, irrigation practices, alternative tillage practices and biocontrol agents were evaluated as means for controlling root maggots.” All registered insecticides, as well as several experimental products, were evaluated, along with alternative methods of insecticide application.

He found resistance to root maggot damage uniformly low in all commercially available rutabaga cultivars. In some trials, the cultivar Golden Ball had less damage than other types, but Waterer said the variety is not valuable in commercial production. However, it might prove useful in a breeding program.

The impact of planting date differed between sites and years. When planted after late May, there was an unacceptable reduction in yield potential. Early planting increased the duration of exposure to the maggot, which increased the damage.

Because of the egg-laying habit of the female maggot fly, it was thought that a one-metre barrier might prevent females from accessing the crop. The subsequent fencing trials were ineffective, however.

Rutabagas benefit from abundant, uniform soil moisture, but these conditions encourage egg laying and development of the root maggot. Irrigation had no impact on yield or maggot damage, and the dryland crop was clearly drought stressed.

Drip irrigation to apply insecticides was also tried. It delivered the chemicals more efficiently than other systems, but the economics of drip irrigating a low-value crop such as rutabagas is questionable, said Waterer.

So-called chemigation via drip lines may be more attractive in higher-value crops such as broccoli.

A form of biocontrol, predatory nematodes, were tried, but there were no significant differences in yield or degree of maggot damage for any of the nematode treatments.

“Insecticides that are currently registered were also evaluated, but few provided any significant degree of control relative to the non-treated controls,” he said. “This suggests their application represents an ineffective and costly procedure that is potentially harmful to the environment, the customer and the applicator.”

Transparent crop covers are commonly used to protect high-value warm-season crops from cold and insects. Their use provided a consistent and significant degree of crop protection from maggot damage, but it came at the expense of total yields.

“In conclusion, we found the most effective treatments – drip irrigation, crop covers or multiple applications of insecticides – were also labor intensive, costly, or of questionable safety to the consumer. In short, more research into maggot control is required,” says Waterer.

Research is continuing in collaboration with Julia Soroka of Agriculture Canada in Saskatoon. Soroka is studying the problem of root maggot in canola.