Shifting energy production from hydrocarbons to renewables is an on-the-ground reality in southern Alberta.

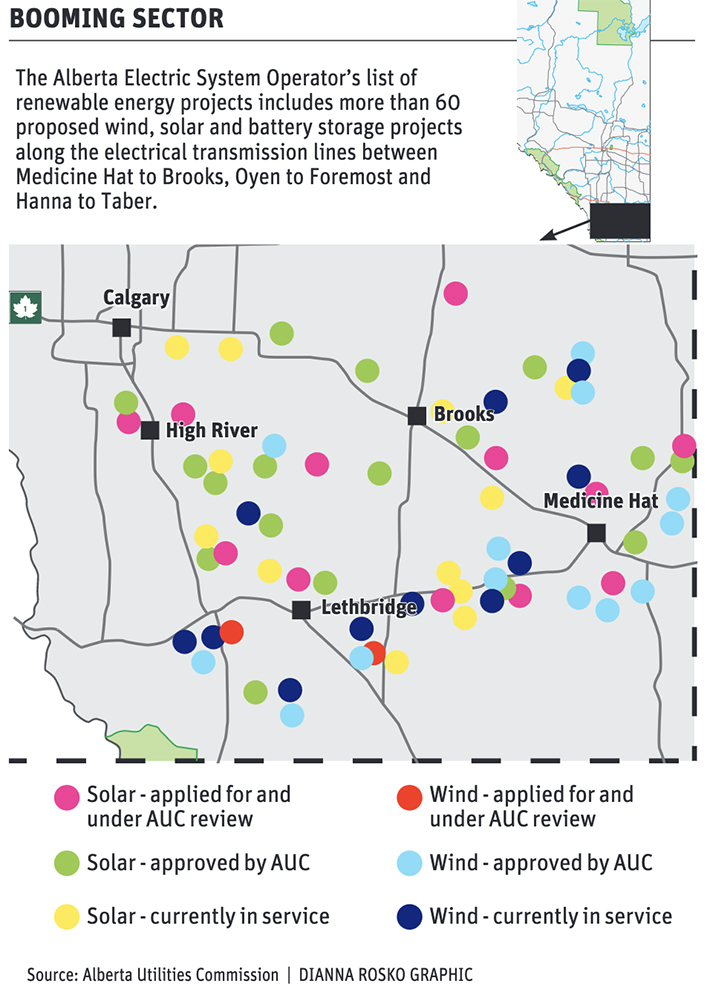

Along the electrical transmission lines between Medicine Hat to Brooks, Oyen to Foremost and Hanna to Taber, there are more than 60 proposed wind, solar and battery storage projects on the Alberta Electric System Operator’s list.

Those projects carry with them an expected capacity of close to 10,000 megawatts of electricity production, while more than 800 megawatts of solar and wind farms with a capacity of 800 megawatts were energized along these corridors in October and November 2022.

The job board at Medicine Hat’s Crescent Heights High School has postings for solar installers and wind techs with nothing connected to the oil and gas sector.

Casual observers across communities in southeastern Alberta are as likely to see service vehicles attached to renewable energy construction firms like Borea and MasTec as those connected to the oil and gas sector.

The growth of renewable sources of energy comes as conventional oil production outside of the oilsands has dropped to a little more than 16 percent in Alberta and no new exploratory gas wells being drilled in the province in 2022, according to the Alberta government’s economic dashboard.

Millions in private sector investment are being poured into southern Alberta through the province’s deregulated energy market, which allows any company that can navigate the regulatory regime to build power production facilities.

But all that renewable energy development comes with a cost to agriculture, as well as social and environmental well-being.

“I don’t think anybody anticipated just how many projects are going to be happening in southern Alberta,” said Phil Horch, president of the Grasslands Naturalists based in Medicine Hat.

Horch said landowners are growing concerned about the footprint these projects leave on the landscape and, while the Grasslands Naturalists support renewables, they fear the impacts if they are built on native grasslands.

Aira Solar’s proposed 450 megawatt project near Seven Persons, Alta., is one such development.

“The project is so large that it will interrupt the movement of antelope, it might have impacts on water and drainage,” said Horch. “There is more and more controversy developing over just the huge number of projects that are being considered for southern Alberta.”

Even when a suitable site like that of the old Medicine Hat Co-op Fertilizer plant is identified, where a 325 megawatt project called the Saamis Solar Park is being proposed, Horch said there are concerns about the scale of the proposals.

“When (development planning) was initially approved, it was going to be on former industrial land, which was fine with us. That’s where it should go,” Horch said. “But then subsequently to getting approval, the developers of that project decided to expand it massively onto native grasslands.”

That could put at risk the already endangered tiny cryptantha, a small native prairie plant with only a few known locations in Alberta, including near the proposed Saamis Solar Park.

That’s just one of many endangered species that live on one of the largest unbroken tracts of native range in the country.

On the other side of southern Alberta, along the Eastern Slopes of the Rocky Mountains, the Municipal District of Pincher Creek hosted Canada’s first commercial wind farm.

Built in the early 1990s, Cowley Ridge was a 57-turbine project with a generating capacity of 17 megawatts. It also became one of the first renewable sites to be decommissioned.

Reeve Rick Lemire said he doesn’t believe there were any hitches in the decommissioning and the technology is changing by reducing the footprint, highlighting Cowley Ridge now supports 15 turbines that can produce 20 megawatts.

The turbines have been a good source of revenue for the rural municipality, he added, bringing in up to $4 million in taxes and creating around three dozen permanent jobs directly attached to wind power in the community of 3,000.

“For years, they just kept coming in and coming in,” said Lemire. “And people saw their tax rate kept low because of the revenue from the taxes on the windmills.”

While initial surveys conducted by the MD of Pincher Creek showed support for continuation of wind power development, Lemire said that’s beginning to change along with a willingness to pay more in taxes to see less renewable projects.

“We did our municipal development plan and one of the things we did was put a halt on (turbines) for two years to see if we could get a study to see if we do allow them, where should they go,” he said. “People want some viewscapes left untouched.”

Meanwhile, work continues in neighbouring municipalities, causing more transmission line development crossing through the Pincher Creek district, said Lemire.

As well, a solar project is being proposed in the municipality.

“I think our council is pretty wary of the fact that good farmland should be kept farmland. We’re having trouble feeding the world right now with crops and you are taking good farmland away and putting them there,” he said.

In the County of Forty Mile in southeastern Alberta, Reeve Craig Widmer also said the revenue generated from renewables has proven a boon for the municipality. But unlike in Pincher Creek, it’s helped replace revenue lost from oil and gas rather than create a new source of tax dollars.

“It used to be oil and gas paid about 80 percent of our taxes and now they are down to 20 percent,” said Widmer. “Renewables have picked up 60 percent.”

However, that applies only when oil and gas companies actually pay the taxes they owe, said Widmer, adding that some haven’t, leaving a $3 million shortfall.

Like Pincher Creek, renewables produce around $4 million in taxes for the municipality of 3,500.

Some welcome the additional revenue, while others fear the developments are taking agricultural land out of production.

“So, it’s a tough situation for us to make a decision whether to change the land-use bylaw to let some of them on there,” he said. “But we don’t have much choice there because the AUC (Alberta Utilities Commission) approves all these projects.”

What’s likely to slow development will be the lack of transmission line capacity, which is nearing its limit, said Widmer.

Overall, it’s a bit of a conundrum with residents not wanting cuts in services or a near doubling of the mill rate to replace tax revenue lost but also not necessarily supportive of more projects being built.

Site remediation is also a concern.

“There are a lot of people against renewables because they don’t think they work. They think they’re just collecting carbon credits and when that program leaves, they are just going to up and leave these things. Kind of like oil and gas,” said Widmer.

For Horch, he said there must be more study on the cumulative effects of so many projects being built so quickly.

“We’re maybe caught a little off guard by the speed and the size and the number of all these projects in a very short time,” he said. “I don’t think we’ve done a lot of assessment of what the impacts will be long term, through this happening as quickly, as largely as it’s happening.”