University scientists seek growers from Manitoba and Saskatchewan to provide samples as part of their pest research

Glacier FarmMedia – Researchers from the University of Manitoba want to know about bug problems in stored grain.

It’s the fourth year of a Canadian Centre for Grain Storage Research project on grain pests. The centre is located at the university and the insect research project is part of the Prairie Bio Vigilance network.

The network hopes to proactively identify invasive species of pests, disease and weeds across the Prairies, facilitating quicker response. Research is wholly based on farm volunteer samples.

Read Also

Using artificial intelligence in agriculture starts with the right data

Good data is critical as the agriculture sector increasingly adopts new AI technology to drive efficiency, sustainability and trust across all levels of the value chain.

Researchers in Lacombe, Alta., and Lethbridge have been studying wheat diseases and invasive wheat weeds. Vincent Hervet, a stored product entomologist with Agriculture Canada and adjunct professor at the U of M, has been addressing the pest side.

“My mandate is to study the detection, prevention and control of insects in stored products,” he said. “Stored product is any stored food, from the beginning when the grain is stored into bins, all the way down to retail.”

Identifying pests before they spread is critical to farm production and market maintenance.

Hervet’s survey is the first such interprovincial effort in Canada. Since 2020, the team has surveyed 27 farms across Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The work has been complicated by pandemic travel restrictions, time constraints and participants dropping out.

“Last year, because of the drought, many people we contacted told us, ‘you can come if I have grain, (but) chances are that I won’t have grain.’ And sure enough, many people told us, ‘I just don’t have enough grain,’ or ‘the elevator called me immediately after harvest. I couldn’t keep the grain for one month. It’s already gone.’”

International market factors also greased the wheels of the value chain. The war in Ukraine has limited global supply, so much of the grain Hervet hoped to tap was sold before researchers obtained samples. They resorted to sampling some of the same farms as in previous years, though new sites would have been preferred.

This year, the survey is taking place in Saskatchewan and Manitoba and Hervet is looking for new participants.

“We identify the insects and then we tell the farmers what we found and if there is a need to be concerned,” said Hervet. “So that could be interesting for the farmers to know what there is in their bins. And we also provide a number of recommendations on what to do to prevent those problems.”

Final study results will indicate the area of a municipality where bugs are found, but will not mention specific farms or farmer names, he said.

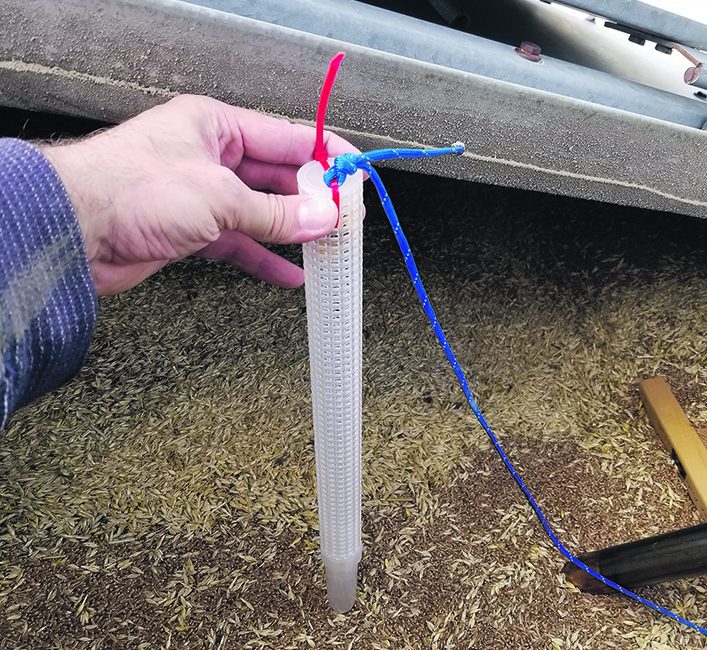

Sampling is done after grain has been in the bin for at least a month, but before weather gets so cold that insects stop moving. Hervet’s team places insect traps in the bin and in the bin yard and leaves them for two weeks. Samples are collected from multiple bins in the same yard.

Bin traps use a pitfall design. Holes are small enough for insects to fall through, but not grain. Bin yards are set with multi-funnel traps to measure populations of flying beetles, and bucket traps are used for moths. Both styles are fitted with pheromone bait.

Researchers also measure grain and grain bin temperature and moisture.

“Overall, we didn’t find anything new,” Hervet said of results so far. “We only found known species, but also the most common species. We didn’t find anything rare either.”

Rusty grain beetles have been the primary finding, researchers noted. The insect is common on the Prairies, but hard to spot without traps or grain tests.

This is the last year the team will go to farms, but Hervet hopes to keep the surveys alive. He’s pondering an exchange program in which farmers would be provided with traps and would submit samples.