GUELPH, Ont. – For almost two hours last Friday evening, Camrose, Alta., organic grain farmer Steve Snider listened to organic ideologues complain about government and corporate plots.

It did not sound like the view of the world he has on his export-oriented, large-scale grain operation.

The public forum at a national organic conference Jan. 29 was dominated by smaller producers or advocates who see organic farming more as a movement, an ideology and a lifestyle choice than a commercial enterprise.

They also see themselves as the

Read Also

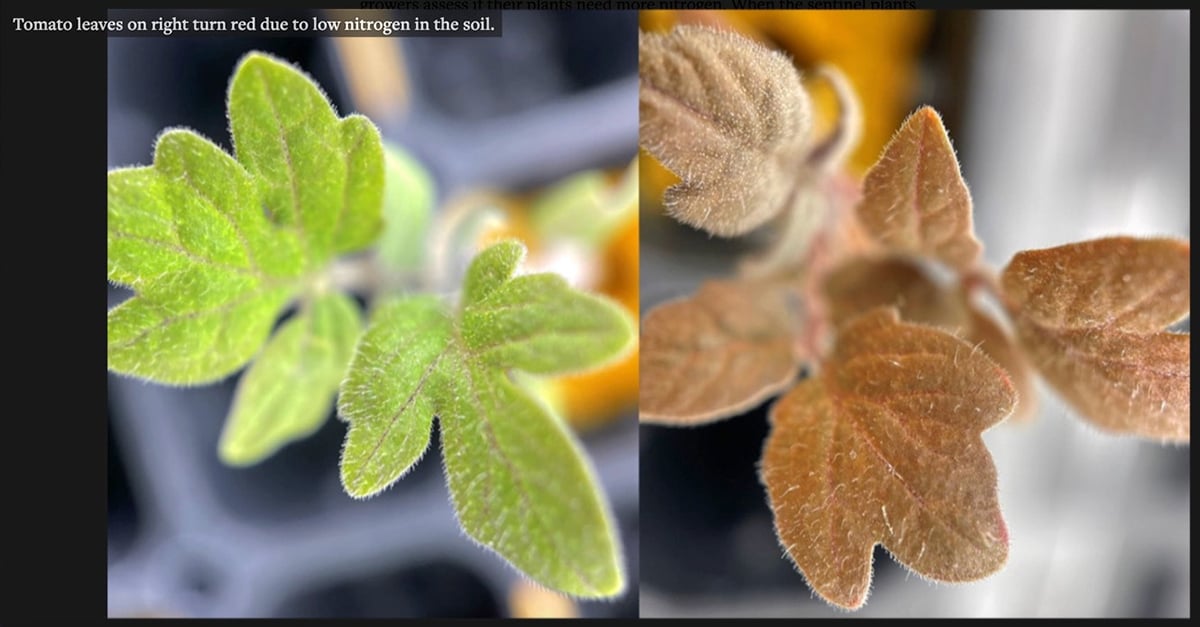

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

future saviors of the food supply as they see the now-dominant corporate and chemically dependent food production system breaking down.

There were complaints from a number of speakers that efforts to create and enforce a national certification program is a corporate or government way to control organic farmers.

Joel Salatin, a Virginia organic farmer, keynote speaker and apostle of getting government out of agriculture, argued that government-enforced standards are not required.

In fact, government is the enemy, supporting the “existing satanic paradigm” of agriculture, he said.

A lineup of producers from across Canada talked about organic agriculture being properly aimed at local self-sufficiency, rather than large commercial or export operations.

Then, it was Snider’s turn at the microphone. He grows 1,600 acres of organic grain, he told the forum. He cannot depend just on local markets for sales.

The group seemed surprised at the scale. Many producers at the forum raise crops on a few acres.

“Are you making money?” asked moderator Tomas Nimmo.

“I didn’t walk here,” replied 30-year-old Snider. There was some applause at this example of organic competing in the big leagues.

Still, Snider said he understands his operation and his farming attitude do not match the reigning ideology of the organic sector.

While he has been involved in the struggle to take organic grain exports away from the Canadian Wheat Board, many at the Guelph meeting argued that the proper marketing strategy is a one-on-one relationship with a local customer.

At times, the public forum became an attack on free trade deals or a debate on whether organic agriculture and vegetarians are natural allies.

Snider said it is encouraging that more people are taking interest in organic production to attend such a forum. But much of the debate left him cold. As an exporter, he supports a national certification program as both a marketing tool and for consumer protection. But he does not think organic can confine itself to local markets.

And Snider said government is needed to monitor and enforce standards.

“The ideology of my business clearly does not always fit with the ideology of the business as shown here,” he said in an interview after the forum. “People seem to see this business in idealistic terms but there are some grim realities out there. There is a market to compete in.”