NORTHEASTERN ALBERTA – It was the second last stop of the day, but the

farmhouse was still a shock for Blair Rogers, a veteran special

constable for the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

“People live here? They can’t possibly live here,” Rogers said, looking

at the faded pink house.

Part of a scaffold covered the front step, and ripped garbage bags and

weathered papers were tossed beside the step. Old oil jugs were hidden

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

in the long grass and abandoned vehicles circled the yard like a rural

Stonehenge.

“That’s a 2002 tag on the licence plate,” said Rogers, confirming the

vehicle parked in front of the house wasn’t abandoned.

Then he saw a shadowy figure in a window and Rogers knew he’d come to

the right farmyard.

A day earlier, someone had phoned the

Alberta SPCA office in Edmonton about 10 to 15 skinny horses in a

pasture with little feed.

On his way to the house, Rogers saw the near skeleton-thin horses

grazing at the foot of a hill trying to find feed in a sheltered area.

“There is absolutely no grass, it’s right down to nothing.”

During a first visit like this, Rogers gives the owners a chance to fix

the problem before seizing the animals. He assesses the situation and

tells the owners how he expects the problem to be fixed and gives them

a deadline.

“This one is going to be faster than others because there’s some fairly

skinny horses.”

After six years on the job Rogers is still amazed by some farmers’ lack

of logic.

“People are under the impression if there’s snow there’s got to be some

food underneath. But if there’s no food in the fall, it’s not going to

appear in the winter.”

Alberta’s Animal Protection Act gives SPCA officers the authority to

enter farmland and premises, except the home, if it is believed animals

are in distress. Animals must have adequate food, water and shelter.

Even the SPCA constable can’t agree on what is adequate shelter. Does a

good bluff of trees offer the same protection as a three-sided pole

barn or a rusty Massey Harris combine?

“There’s all kinds of junk to hide behind,” Rogers said, looking around

one yard full of old trucks and tractors on blocks.

Skinny animals and junky yards seem to go together.

“There is a general lack of respect. They don’t take care of the yard

or themselves and the animals.”

At the second stop, a farm woman met Rogers in the yard in her stained

sweat pants, rubber boots and a dirty quilted work shirt hanging like

ribbons from crawling through too many barbed wire fences.

It’s about the eighth time Rogers has been at her farm since January.

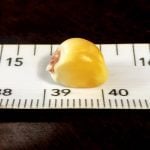

He already confiscated the 40 horses once, but returned them when he

was assured they would be fed. Under the agreement, she must feed the

horses one tote bag of alfalfa pellets, about one tonne, every five

days, plus hay. Each tote costs about $200.

He tells the woman when he comes back next week he wants to see

receipts for the pellets. He doesn’t believe she is feeding enough. He

knows it’s only his pressure that keeps her on track.

“You get lied to enough that you have to do it to be sure the animals

are cared for,” said Rogers, a graduate of the Northern Alberta

Institute of Technology’s animal health technology program.

At another farm, Rogers stopped to recheck a group of animals. On the

previous visit Rogers had told the man he needed to get his dog’s ears

cleaned, trim a donkey’s hoofs and look after an old injury on an

Appaloosa stallion’s leg.

The dog and donkey had been treated, but it didn’t look like the

stallion’s leg had been looked after. Just above the hoof the back leg

was dirty and swollen from what looked like an old wire injury.

Originally, there must have been small wire paddocks, but the fence

posts had fallen over years ago and the wire was spread across the yard

like old twine.

Looking for more animals, Rogers walked into a long pole shed that at

one time must have had a 3.6-metre ceiling. Now he walked up a manure

ramp and had to bend over to stop his head from hitting the rafters

because of years of manure buildup.

At the end of the dark barn a mare and foal, a miniature horse and a

mule with a broken leg stood in a makeshift corner corral.

“There’s no reason to keep a mule with a broken leg. It’s not like a

high price Thoroughbred you want to save,” Rogers said while writing up

a notice that orders the farmer to put the mule out of its pain within

24 hours.

He will also recommend the farmer receive peer help from Alberta

Foundation for Animal Care members.

Other farmers will try and teach the man he can’t have stallion and

mare draft horses, light horses, donkeys, miniature horses and donkeys

in the same area.

In 2000, the last year for statistics, Alberta’s seven special

constables investigated more than 1,790 complaints, driving more than

400,000 kilometres. There were 80 animal seizures, 42 surrenders and 20

court cases.

While there are success stories, it’s the never-ending complaints that

wear Rogers down.

“I could probably deal with animals in distress. It’s the people and

the driving that get to me,” he said, driving 670 kilometres that day.

“It’s not difficult to do it right. It just takes a little bit of time

and a little bit of desire.”