John Pomeroy hinted during a beef conference in March that there could be a possible water shortage in parts of Saskatchewan and Alberta this year.

Those murmurs are now full-blown alarm bells as we head into summer.

“Things have changed, they’ve become worse,” Pomeroy, a director with Global Water Futures, said a few months after he released his snowpack forecast.

Read Also

Farmland advisory committee created in Saskatchewan

The Saskatchewan government has created the Farm Land Ownership Advisory Committee to address farmer concerns and gain feedback about the issues.

“The monitoring is done because the snow has melted early. Depending on where you were, it varied a bit, but on average, it was roughly two-thirds of normal levels for snowpack in the mountains.”

The snow in crucial areas has melted two to three weeks early, mirroring 2023, which Pomeroy noted was a “disastrous” year. Water restrictions were issued in Calgary and surrounding communities such as Claresholm and Cardston, and the Alberta Energy Regulator issued a bulletin requesting water licences be proactive in planning for water shortages and implementing conservation techniques, which irrigation districts did in 2024.

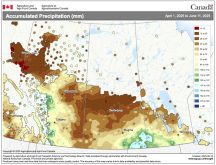

That period has been followed by little help from Mother Nature, with below normal rainfall and precipitation in the southern Rocky Mountains, from Lake Louise south.

“It puts us in a very, very bad situation. All the sites I’ve monitored, the snow is gone,” said Pomeroy.

Some of his monitoring in previous years has extended to the end of July.

“We were hoping for some big storms, but we didn’t get them.”

Pomeroy monitors 35 stations in the Rocky Mountains, from Jasper to Kananaskis, including the mountain headwaters of the Bow, Oldman, Red Deer and North Saskatchewan rivers, which have had some of the lowest levels he has ever seen.

Alberta Environment’s snow surveys since Pomeroy’s presentation in March showed some in the lowest 10th percentile of decades of measurements. Jasper’s past winter was the driest on record with 138 years of data from Environment Canada.

Depending on the sub-basin, some of the snow surveys have been in the lowest three years of the last 40.

The province has low-flow predictions in many of the tributaries for the Bow and Old Man rivers, but Pomeroy said even more attention is needed.

“I’m surprised there isn’t a greater sense of urgency this year.”

Wildfires have been raging in northwestern Alberta, claiming more than 1.2 million acres as of early June, according to the National Post. Low snowpacks help provide the tinder for big fire years such as what is currently sweeping across Western Canada.

Pomeroy, chair for Canada Water Resources and Climate Change at the Global Institute for Water Security at the University of Saskatchewan, has travelled the globe trying to rally international leaders to invest more resources in building better weather-predictive technology for the future.

Recent travels took him to Tajikistan, which is having the same issue with lower snowpacks, melting glaciers and less water for irrigated farming.

“We want to forecast to farmers months in advance what they can expect,” Pomeroy said.

“I’m not a predictions service agency — provincial and federal governments do that — but I could see this coming in January.”

He said the meeting in Tajikstan was attended by 2,000 people from around the world and resulted in the Dushanbe Declaration, which called for better monitoring and weather warning systems.

“It’s a new reality we are facing, and Alberta is not alone.”

With better information, farmers can decide what seeds to buy with more water-efficient crops that flourish in warmer conditions along with long-range water storage options.

“We need to move further in better predictive systems,” he said.

“Farmers can make better decisions in what seed to buy to get bang for their buck, operate reservoirs to store more earlier water and catch it earlier in the season.”

He said Mother Nature is forcing people to become more efficient in a wide variety of water-retention practices.

“We can use nature, we can use mountain wetlands, use groundwater where we can,” he said.

“It’s as expensive as can be, but (also) looking at the operation of our reservoirs or increasing their capacity or number.”