In our last issue, we looked at how a weak La Niña might influence this winter’s weather. This time, we’ll explore two more key players: early snowpack development across Siberia and a warmer-than-normal northern Pacific Ocean.

When snow piles up early over Siberia in September or October, it increases surface reflectivity (albedo), sending more sunlight back into space and cooling the lower atmosphere. This rapid cooling strengthens the Siberian High.

The resulting temperature contrast between the frozen north and the still-mild south sharpens the baroclinic zone, which is the boundary where large-scale weather systems form.

Read Also

Canadian Food Inspection Agency red tape changes a first step: agriculture

Farm groups say they’re happy to see action on Canada’s federal regulatory red tape, but there’s still a lot of streamlining left to be done

As this pattern intensifies, atmospheric energy ripples upward as Rossby waves, giant undulations in the jet stream. These waves can reach into the stratosphere, disturbing the polar vortex.

When strong waves weaken or displace the vortex, it leads to higher pressure over the pole and weaker westerly winds at mid-latitudes, a pattern known as a negative Arctic Oscillation (AO) or North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO).

When the AO turns negative, the jet stream becomes wavier, allowing Arctic air to plunge southward. This typically means colder, snowier conditions across central and eastern North America, while western regions experience milder, drier weather.

The timeline is often predictable: early snow in October, wave amplification in November, stratospheric disruption in December and surface impacts by January or February. In short, Siberian snow can help set the stage for North American cold snaps months later.

However, like La Niña, this connection is probabilistic rather than guaranteed. Other global patterns can strengthen or override the snow signal.

This year, Siberian snow cover advanced early but slowed in recent weeks, leaving its ultimate influence uncertain.

The second factor shaping our winter is the warmer-than-normal northern Pacific Ocean.

When this region runs hot, the ocean releases extra heat and moisture, building a dome of high pressure that alters normal circulation patterns. The Aleutian Low, a semi-permanent low near Alaska, often weakens or shifts northward, reshaping the path of the Pacific jet stream.

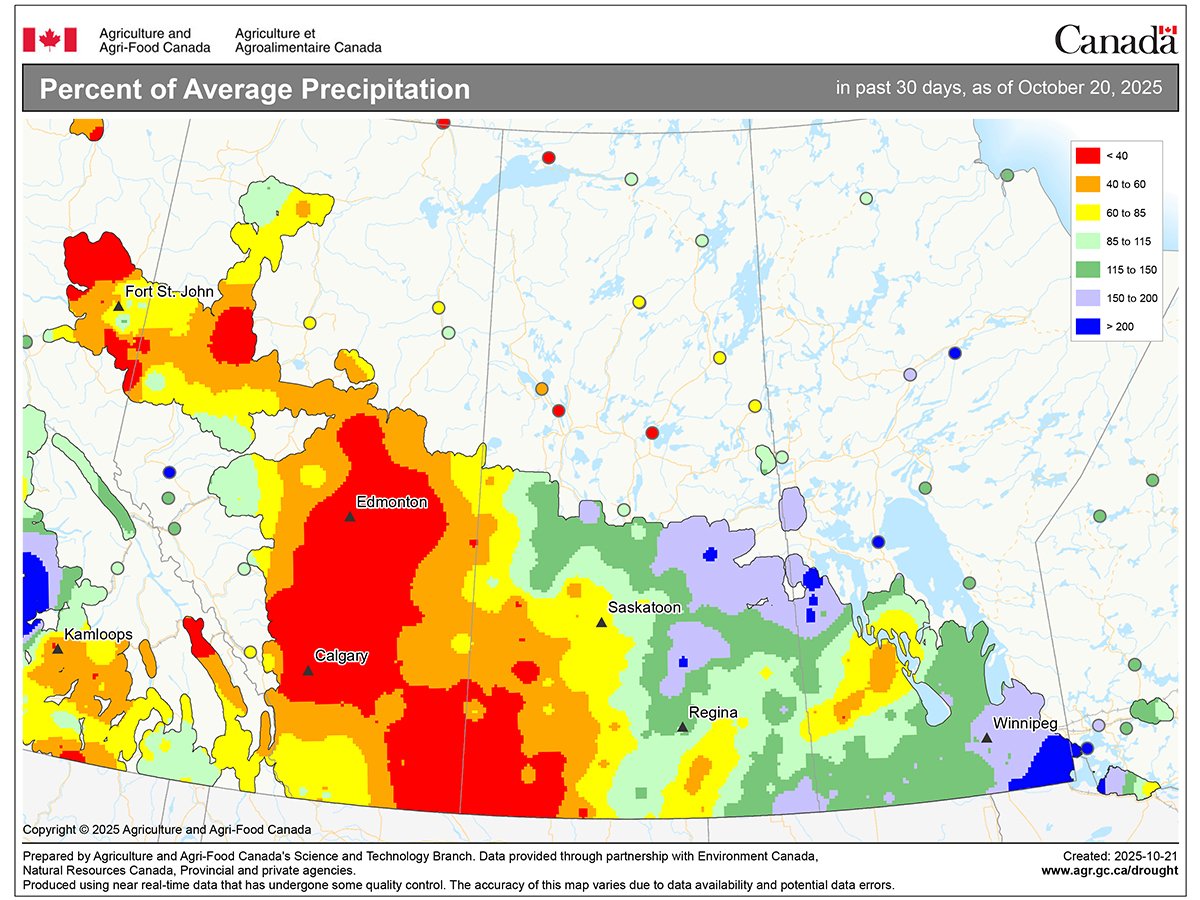

A persistent warm zone in the North Pacific tends to produce a ridge of high pressure over western North America. This ridge deflects storms northward, leaving the West mild and dry, while a downstream trough deepens over central and eastern North America.

For the Prairies, that means western areas often experience milder, drier winters, while eastern regions see alternating warm and cold spells, leading to more storm systems and above-average snowfall.

When we combine these factors, a weak La Niña, early Siberian snow, and a warm northern Pacific, it’s easy to see why long-range winter forecasting is so complex. Each influence pushes the atmosphere in a slightly different direction.

In our next issue, we’ll try to make sense of how these forces may align in the latest winter weather outlooks.