WINNIPEG — In the last five years, the governments of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Canada have committed more than $2 billion to expand the acreage of irrigated cropland in Western Canada.

That’s positive, but Stephen Johnston is urging governments and private investors to do much, much more.

Johnston, director of the Omnigence Asset Management investment fund, says irrigated farmland is a significant opportunity for Canada to boost productivity and gross domestic product.

Read Also

Saskatchewan project sees intercrop, cover crop benefit

An Indigenous-led Living Lab has been researching regenerative techniques is encouraging producers to consider incorporating intercrops and cover crops with their rotations.

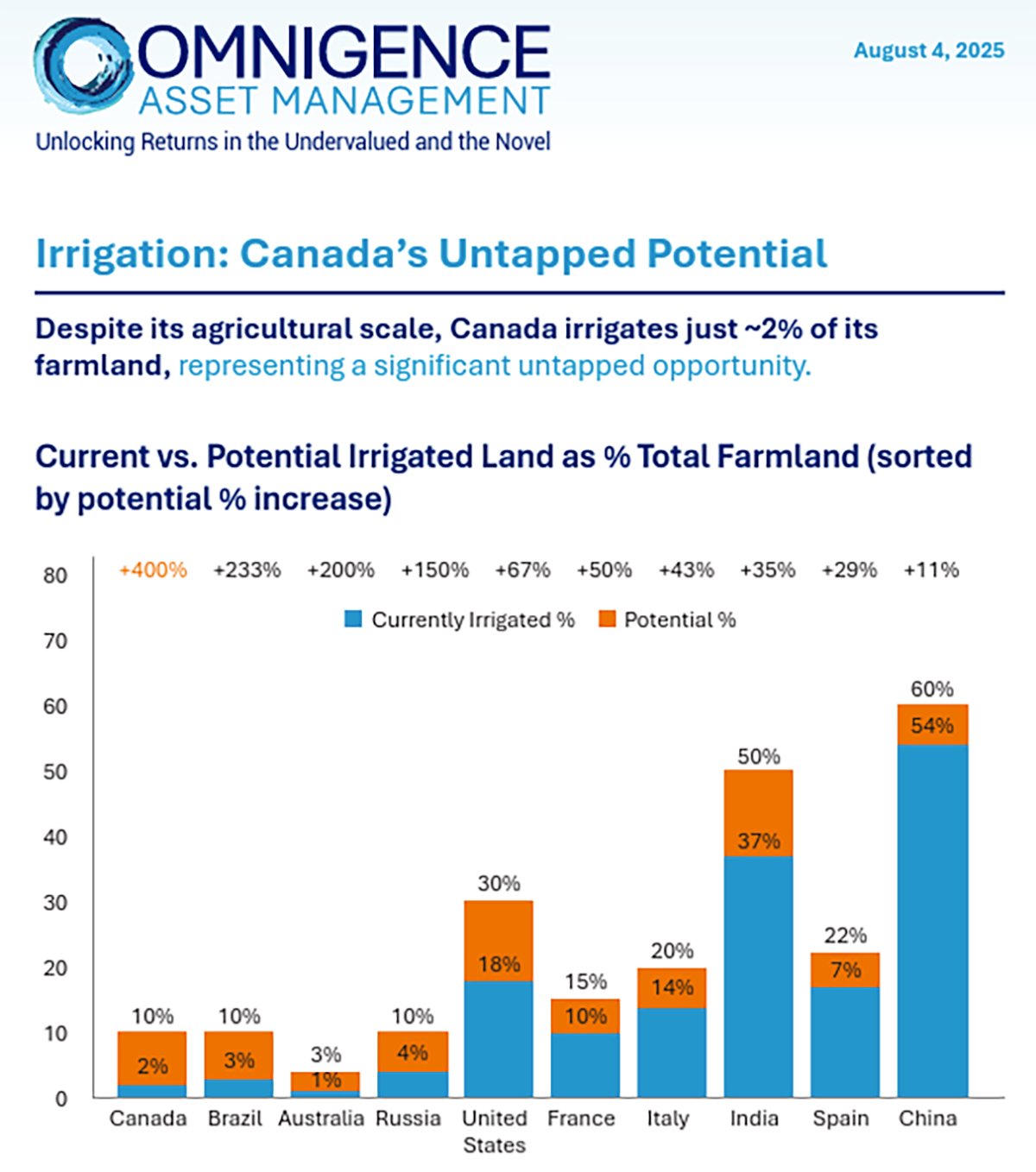

“Despite Canada’s large agricultural footprint, its irrigation (of farmland) lags far behind global peers,” Omingence said.

“Canada has the potential to increase its irrigated acreage by up to 400 per cent… Irrigation is … a catalyst for improving farmland productivity, enabling access to higher-value crops and driving land value appreciation.”

Omnigence, which owns about 140,000 acres of farmland in Western Canada and controls other assets, published a brief report on the potential of irrigating more farmland last month.

Only two per cent of Canada’s farmland is irrigated, much lower than countries such as France and the United States, where 10 and 18 per cent of farmland is irrigated, the report says.

According to Statistics Canada:

- In 2022, Canada had 1.87 million acres of irrigated farmland.

- Most of that, 1.36 million acres was in Alberta.

Omnigence says Canada has the potential to irrigate 10 per cent of its arable land. Johnston and his team looked at provincial reports and other studies to arrive at the 10 per cent estimate.

“(It) is based on water availability and land that would be receptive to irrigation,” he said.

“It’s a collection of data that’s aggregated together. There’s no specific report that says the potential is 10 per cent.”

Canada is nowhere near that number, but Alberta has recently added to its irrigated acres.

In 2020, the province, the federal government and a loan financed by the Canada Infrastructure Bank came together on an $815 million project to irrigate an additional 200,000 acres in the province.

Saskatchewan also wants to scale up irrigated land, which was only 133,000 acres in 2022.

The province is moving forward with the Westside Irrigation Rehabilitation project, which would add 100,000 acres near Lake Diefenbaker.

“The total cost is estimated at $1.15 billion, which will be shared between the provincial government and producers who participate in the project,” says a provincial report summarizing the results of a public meeting held in April.

“The economic analysis for the (project) shows an increase in gross domestic product of $5.9 billion.”

Irrigated land can boost economic growth because it increases crop yields and lowers yield volatility. It also allows farmers to grow high value crops.

“The returns (from) non-irrigated land to irrigated are very high,” Johnston said.

Ideally, an investment in irrigation infrastructure would come from private capital, Johnston added.

It’s a matter of setting up the right structures and incentives to encourage that investment.

Private money would be helpful, but a combination of public and private investment will likely be needed.

Which leads to a question: would taxpayers be willing to spend tens of billions to build dams, reservoirs and irrigate more farmland on the Prairies?

“Unfortunately, making big capital (investment) decisions is very political in Canada,” Johnston said.

“The Liberals will agree to fund battery plants and solar panel manufacturing. Conservatives will typically endorse funding in the natural resource (sector).”

Producing more food by irrigating land could be something that progressives and conservatives both support, Johnston added.

All of Canada could use more irrigated land, but the largest opportunity for more irrigation is in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Johnston said.

Johnston said Omnigence published its report on irrigated farmland because Canada desperately needs more capital investment and economic growth.

“Otherwise, our standard of living is going to fall,” Johnston said.

“We (are) just trying to bring something to public attention that … nobody thinks about in Canada.”