WINNIPEG — Western Canada is now warmer than it was in the 1950s, and that trend is expected to continue, says a researcher with Environment and Climate Change Canada.

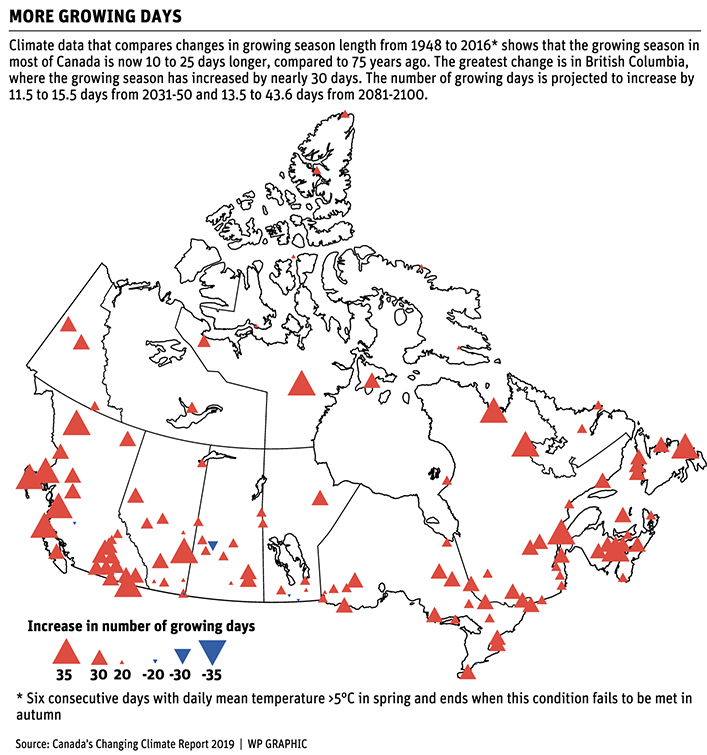

Since the late 1940s, the growing season on the Prairies and British Columbia has lengthened by 15 to 30 days. A lot depends on location, but it seems like British Columbia and Alberta are getting warmer — and faster — than Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

“On the Prairies, it’s looking like 15 to 20 days (longer),” said Barrie Bonsal, who studies climate impacts on water availability.

Read Also

Russian wheat exports start to pick up the pace

Russia has had a slow start for its 2025-26 wheat export program, but the pace is starting to pick up and that is a bearish factor for prices.

“In B.C., it’s showing 30 to 35 days longer.”

Those figures come from the federal government’s Canada’s Changing Climate Report from 2019.

Projections show that this warming trend will continue in the coming decades. It’s possible that by 2050, the Prairies will add 11 to 15 days to the growing season.

Bonsal shared a graphic from the report that illustrates changes in the growing season from 1948 to 2016.

In many regions of B.C., the length of the growing season has jumped by 30 to 35 days. In southern Manitoba and parts of Saskatchewan, it’s more like 10 to 20 days.

It’s difficult to know for certain if this trend will continue, but government predictions say that Western Canada will soon have more days for crops to mature. That climatic change should benefit crop yields and production.

“Yes, that’s generally the message we’re giving across Canada…. We’re going to be warmer and wetter,” Bonsal said from his office in Saskatoon.

Some of the evidence in the 2019 federal report is similar to the findings of Al Mussell, an agricultural economist from Ontario.

In June, Mussell published a paper on climate change in Canadian agriculture.

He argued that a longer growing season and more warmth should help Canadian farmers.

However, Mussell differs from the government on how to respond to the changing conditions. Reducing emissions from agriculture is important, he said, but it shouldn’t be the priority.

Instead, public policy should focus on adaptation.

“Being at the northern fringe of viable agriculture globally, a subtly warmer and wetter situation is surely a benefit for Canada”, said Mussell, the research lead with Agri-Food Economic Systems, a group in Rockwood, Ont.

“But there are many layers to climate change in agriculture.”

In his paper, Mussell points out that Canada is one of the few regions of the world where crop production could increase because of the changing climate.

Farmers in other parts of the globe, closer to the equator, will suffer because of a warmer world.

Therefore, Canada has an opportunity or a responsibility to produce additional food.

“Canada is a significant net agri-food exporter with capacity to help offset reductions in food production elsewhere in the world, due to the detrimental effects of climate change,” wrote Mussell, who is also the senior research fellow with the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute.

A longer growing season with warmer temperatures does come with risks, such as the spread of fungal diseases and the introduction of new crop pests, Mussell wrote in his paper.

Another federal government document, from Agriculture Canada, supports Mussell’s analysis that there are both opportunities and challenges from a changing climate.

The report, which can be found here, says Prairie farmers will have to cope with more frequent spring flooding, droughts and extreme weather.

On the other side of the coin, there will more days in the growing season.

“Increased frost-free periods may provide opportunities for the expansion of crops … such as corn and soybeans, as well as a potential northwards expansion of agricultural production where soils permit,” the report says.

“Higher CO2 levels may result in greater productivity from crops such as wheat, barley, canola, soybeans and potatoes.”

Mussell makes the same point about carbon dioxide in his report, saying research and common sense indicate that plants benefit from additional carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“Some of these papers he (Mussell) refers to from Ag Canada, looking at CO2 fertilization and more crop production…. I know the author very well,” Bonsal said.

“That’s essentially it. (The crop) likes more CO2.”

The climate models suggest that a longer season for crops is likely, but a large unknown is water.

If air temperatures are warmer in the future, more rain and snow are likely. However, when and how that precipitation falls to the ground could become problematic.

“There’s some equation that says with every degree of warming, the atmosphere can hold seven per cent more water,” Bonsal said, meaning the future climate in Canada should be wetter than the present.

“How this ‘wetter’ is going to be distributed in the future is really the question. The delivery is going to be more in the extremes.”

If 100 millimetres of rain over two days in May becomes commonplace, then water management will be even more critical for western Canadian agriculture over the next 100 years.

“We’re probably going to have longer growing seasons, more heat units,” Bonsal said.

“But it all depends on water…. If you have enough water, I think they (farmers) will do really great in the future.”