WINNIPEG — British scientists have created a pig that’s resistant to classical swine fever, using gene editing technology.

The discovery could have benefits for other livestock because the virus that causes classical swine fever is similar to the pathogen responsible for bovine viral diarrhea in cattle.

“The same genetic edit could theoretically be applied to other livestock species, offering broader protection against disease,” says the University of Edinburgh release that promoted the discovery.

Read Also

Organic farmers urged to make better use of trade deals

Organic growers should be singing CUSMA’s praises, according to the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

The Edinburgh scientists, who collaborated with the animal genetics company Genus and other European researchers, made their discovery by focusing on a group of viruses called pestiviruses and how they interact with pig cells.

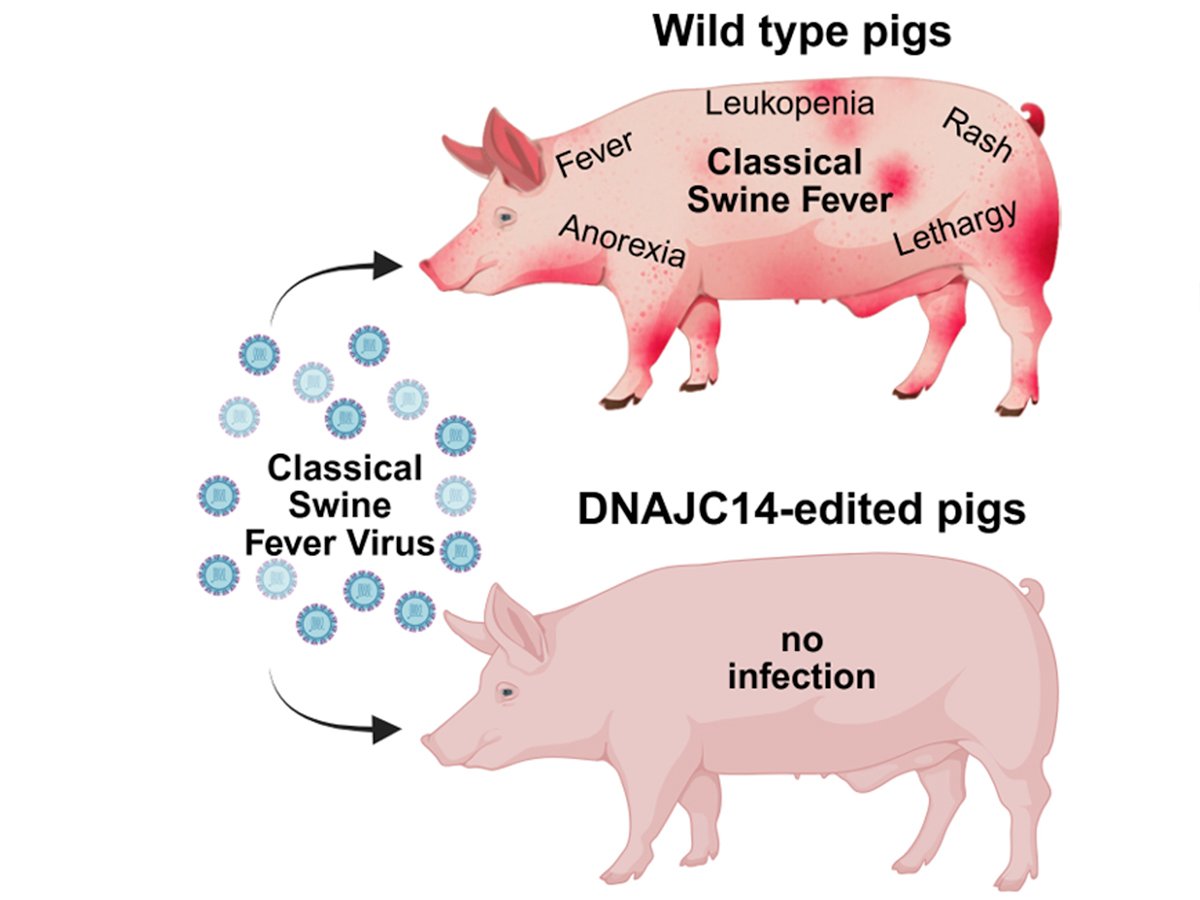

They targeted a protein that plays a large role in pestivirus replication, known as DNAJC14.

The basic idea was to edit the gene that produces the DNAJC14 protein to hopefully prevent the virus from replicating inside the pig.

To test the concept, the scientists edited the target gene in pig embryos and implanted them in sows.

The next step was exposing the pigs (in adulthood) to the classical swine fever virus.

“No signs of infection were detected when young adult pigs with edited DNAJC14 were inoculated with classical swine fever virus, demonstrating gene editing as a viable option for control of these devastating pathogens,” says a paper published in Trends in Biotechnology in October.

Classical swine fever can be a major problem for hog producers in parts of Asia, Africa, Latin America and Europe.

The disease is also known as “hog cholera,” says the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

“The disease ranges from mild to severe and can be fatal, often causing a large number of deaths in affected herds.”

It’s not found in Canada, but a different pestivirus is a problem for Canadian cattle producers — bovine viral diarrhea virus.

BVD is common in western Canadian beef herds and in feedlots, says a University of Calgary factsheet.

It can infect calves in gestation, causing abortions, still births and weak calves. Other BVD symptoms include diarrhea, fever and immune-suppression, increasing the risk for other diseases.

Bovine viral diarrhea is effectively controlled with vaccinations, and recent reports indicate that the majority of Canada’s cattle herd is vaccinated for BVD.

Still, having another tool to control this disease would be helpful and could reduce the need for constant vaccinations.

The University of Edinburgh researchers found that the gene editing prevented the viruses that cause classical swine fever and BVD from replicating inside the embryo.

“If adopted by (livestock) breeders, this discovery could provide a timely addition to the control options available to farming communities around the world,” said the Trends in Biotechnology paper.