A unit train loaded with durum arrived in Thunder Bay, Ont. Dec. 12, culminating months of hard work by a group of Saskatchewan farmers determined to save their rail line.

But it took a complaint to the Canadian Transportation Agency before CN Rail agreed to work with the group of farmers who put the shipment together.

The 83 producer cars were loaded and shipped Dec. 8-9 off a line the farmers say is going to be abandoned by CN Rail.

“It was a great success,” said Rob Lobdell, an Eston, Sask. farmer who helped organize the train. “It went smoother than we could possibly have imagined.”

Read Also

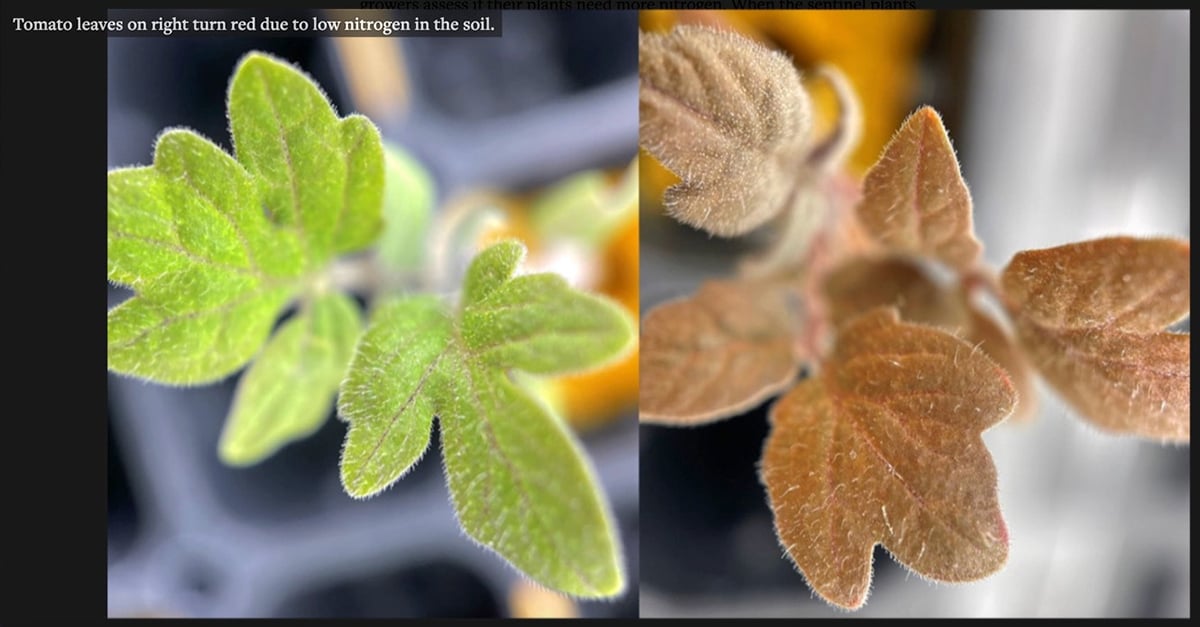

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

However, it didn’t go all that smoothly when the idea was first presented to railway officials.

Three farmers from the West Central Road and Rail Committee were told by CN at a Nov. 12 meeting in Winnipeg that the railway would not co-operate in putting the train together because rail service was no longer being provided on some sections of the line.

“We were told no by CN,” Lobdell said in an interview last week. “We told them we didn’t accept that. They said tough.”

Not prepared to give up, the farmers sent a letter of complaint to the CTA, saying they had the right as shippers to be provided with rail cars.

The CTA asked CN to explain its position and it was only then that the railway decided to sit down with the farmers and negotiate.

Lobdell said the experience shows the importance of maintaining producers’ legal right to load a rail car, which is enshrined in the Canada Grains Act, and the value of having a regulatory body like the CTA.

“It’s time we understand what our rights are,” he said.

“There are certain laws and agencies in place that we have got to take advantage of and if we don’t we will have no control or say at all in five years.”

CN spokesperson Jim Feeny said the railway said no at first because the farmers wanted some cars to be placed on two sections of line where service had been halted in mid-October.

“We didn’t want to do it originally where they wanted the cars,” he said. “That’s where the disagreement was.”

The complaint to the CTA argued that since those sections of line had not been officially abandoned, the railway was obliged to provide service. Rather than fight that issue, the railway negotiated a solution that saw cars spotted on one of the two segments in question.

Bill Woods, another farmer involved in the project, said the experience brings into question statements by big grain handling companies that they can’t get cars delivered to some elevator points on the line.

“If three farmers can get a train after they’ve been denied it, I have trouble accepting that a company with 60 percent market share, that big a customer for the railway, can’t get cars,” he said.