HARDWOOD LANDS, N.S. – Even on the Prairies with its scant 100 years of agricultural history, the Grants’ dairy farm would seem a recent arrival.

But in a province where fishing villages date to the 1700s and where Victorian gingerbread decoration make Annapolis valley farm homes a photographer’s delight, a farm started in 1959 seems a newborn.

Yet the Grant brothers are building their own history, developing a farm their future grandchildren might someday take over.

It was 38 years ago when Donald Grant, fresh from the Nova Scotia Agriculture College (known as the AC) in nearby Truro, started milking cows in this rolling, forested land settled by dairy farming Dutch immigrants.

Read Also

Farmland advisory committee created in Saskatchewan

The Saskatchewan government has created the Farm Land Ownership Advisory Committee to address farmer concerns and gain feedback about the issues.

The Grant family arrived in Nova Scotia in the 1700s, but farming was not their occupation when Donald was young. They lived in the country, but their father worked in the city.

“Mother came from a farm, though, and she wanted to have a little agriculture around. We got a few cows and one thing led to another and here we are today,” Donald said with characteristic understatement.

He and his brothers Peter, Wilfred and Archie and their families now have a farm that is a model of modern production on 600 acres of owned and leased land.

The decision to undertake the latest and biggest expansion was based on the understanding that the second generation of farming Grants will soon finish school and join the dairy business.

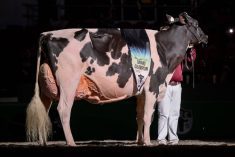

In 1992 the family replaced the milking parlor and in late 1995 started work on a million-dollar, 350-stall barn for the herd of Holsteins.

“We had room for 225 cows in the previous barn we had, but my two sons are here and Wilfred, he has a son who is not here yet but he might, so we had to move into an expanded idea,” Donald said.

“Peter has two girls and they might farm too, you can never tell. The future is on the mind all the time.”

And Karyn, Donald’s wife, joins in with a gentle reminder: “Our daughter, Anne, is going to the AC this year, she’s working on a farm this summer … . It’s right in their blood. All three families were in 4-H. The children really like the rural area.”

Modern technology

The barn is big and bright with free stalls and a slatted floor for easy cleaning. It has a natural ventilation system that automatically monitors the temperature and opens windows when it gets too warm.

It also has a computer operated feeding system that mills and mixes the free choice daily ration. An overhead conveyor belt delivers feed to the stalls.

“We have a lot of cement work and block work and it will have low maintenance and will be easy to keep clean. We want a comfortable place for people to work,” Donald said.

The milking parlor has 32 spaces in a herringbone design. It, too, is computerized. Each cow has an electronic ear tag that identifies it as it walks into the parlor. From a computer panel at each milk station, the two-person milking crew can call up information on the cow such as how long she has been milking and her average daily production.

“It was a growing experience, one step after another, but after a while you get your confidence built up and you become more at ease with large expenditures and budget it out so you are on the cautious side,” he said.

“But when you say a million-dollar barn, how is that cautious? But the time was right.”

The Grants traveled to New York state to get ideas from new dairy operations to see how they will have to be organized when free trade agreements remove the dairy industry’s protections. Although they think they have things in hand for the future, there are other forces at work.

Halifax is about 56 kilometres away, but the airport is closer and bedroom communities and acreages encroach on the farmland.

“I don’t know what really draws them out here, but we seem to be really bombarded by them,” Donald said, adding a developer recently bought 900 acres of land for housing.

Rural versus urban

“They like the country life, but the spread manure doesn’t smell too good. You’re roaring around at five in the morning to make sure the fields get seeded and your working to 10 at night and you become very unpopular.”

And housing drives up the price of land beyond what agriculture will sustain.

The two generations of Grants seem to get along well. Donald handles the finances, Wilfred looks after the cattle, Peter and Archie do the field work. The children, many attending or recent graduates of the AC at Truro, work with their fathers.

The family would like to get milk production up to 10,000 kilograms per cow, from about 7,500 kg now. They have some forested land they’d like to manage better and want to look into growing more of their own feed. On their 600 acres they now grow their own hay and corn for silage. They buy high moisture corn from Maritime sources and some grain from Western Canada and soybeans for protein.

“I guess our goal is always the same: To produce good quality feed and to have a standard of living that is acceptable to everybody,” Donald said.

“I guess we don’t have any magic tricks. It’s just give and take and making it work.”