ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia – Even though the World Trade Organization

insists that its recently launched trade negotiation will help

developing countries enjoy the fruits of freer trade, one of the

world’s poorest countries has decided to stay on the outside looking in.

Girma Bekele, general manager of the Ethiopian Grain Trade Enterprise,

said that a country like Ethiopia has little to gain and much to lose

from freer global trade.

Despite the enthusiasm of some WTO members that liberalized trade is

Read Also

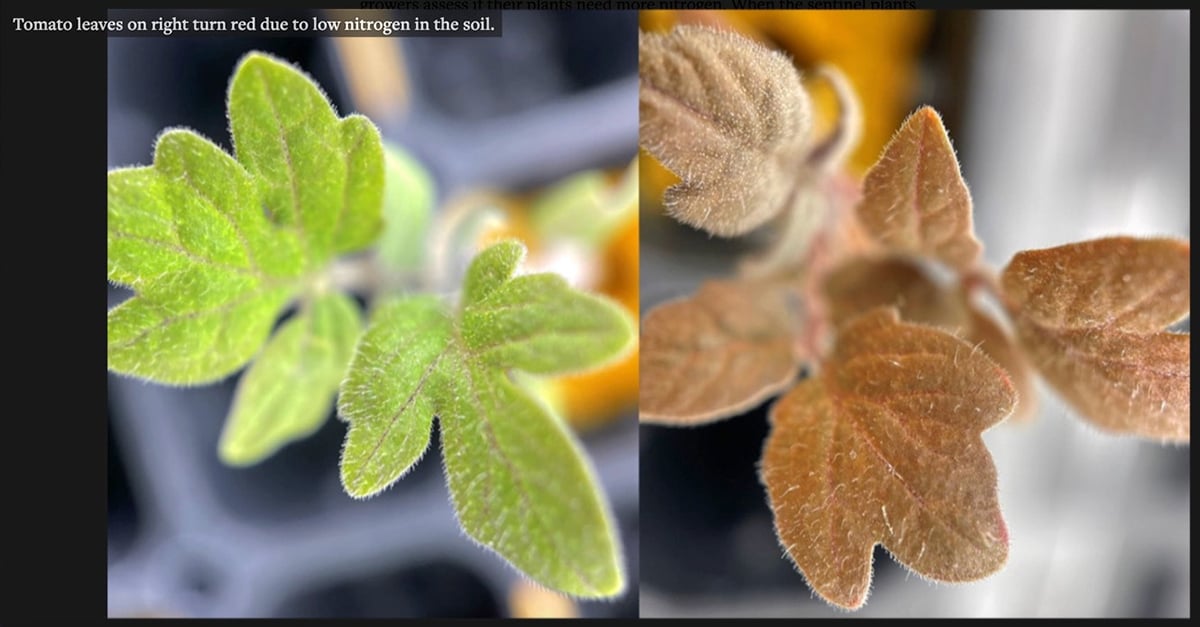

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

the answer to poverty in the developing world, Ethiopia is one country

with doubts.

It doesn’t belong to the WTO.

“The relationship between trade and development is complicated and not

always evident,” Bekele said.

“Even if barriers to trade are lifted, our capacity to compete in

developed country markets or with developed country products is limited

by price, technology and products.”

For example, he said there is a demand in North American markets for

garments, but Ethi-opian standards are unlikely to win favour or be

able to compete.

“What I am saying is that freer trade may help some, but it is a very

difficult solution,” said the head of the government agricultural

marketing agency.

“We are not developed to a level to compete with the competition of

developed countries. A boy cannot compete with a man.”

Weighed against few expected export gains is the spectre of significant

import losses.

“If we allowed zero or low tariffs on maize or wheat, our markets would

be overrun with cheaper products from South Africa or other countries,”

he said.

“Our farmers would be undermined, and maybe destroyed.”

In fact, Ethiopia’s grain farmers are already facing a form of

international competition that undermines their commercial aspirations

– food aid.

It is a criticism that reflects the country’s complicated view of the

tonnes of food aid that flow into Ethiopia every year to feed millions

in the northern highlands where there isn’t enough food.

Increasingly, farmers in other areas of the country say that in years

when the rain comes and they have surplus production, they could meet

more of the internal need, if it wasn’t for the food aid.

Food aid shipments from Canada, the United States and the European

Union sometimes are sold into local markets for cash, depressing

domestic prices and capturing markets that Ethiopian farmers could try

to fill.

Even if it is not sold internally, tens of thousands of tonnes of “free

food” undercut efforts to create domestic markets.

“In years of domestic surplus, imported food aid wheat can take the

place of local domestic produce and that can hurt our farmers,” Bekele

said.

“Of course, in years when the rains don’t come and we don’t have enough

food domestically, we need those food aid imports.”