Snow that has fallen this winter has alleviated some concerns, but problems remain in west-central Sask. and central Alta.

As of Jan. 15, Brandon had 20 to 40 centimetres of snow on the ground.

The range is large; one Environment Canada weather station reported 19 cm of snow, while another reported 40 cm.

Assuming the actual amount is somewhere in the middle, a 30 cm snowpack should help Manitoba farmers, who suffered through a severe drought in 2021.

Unfortunately, the additional snow will not fix the drought that persists in Manitoba and in other parts of the Prairies.

“We’ve received normal (and) in some regions above normal snow (on the Prairies)… but that’s still not enough to recharge the soil, the water supplies and everything else. We’re still in a situation that we’re very concerned about,” said Trevor Hadwen, an agroclimate specialist with Agriculture Canada in Saskatchewan.

“When you look at the long-term (precipitation) deficits that we’re seeing across the Prairies…. As of today (early January) we’re still looking at almost 200 millimetres of precipitation deficits. In large portions of the region…. (a) normal snowfall amount isn’t going to provide a whole lot of relief to the drought that we’ve had this past summer.”

Hadwen was referring to the amount of snow and rain that fell from Jan. 1, 2021, to Jan. 1, 2022. If the calendar is turned back further, to September of 2020, the moisture deficit is more severe in many regions of Western Canada. The fall of 2020 was exceptionally dry, with only 25 mm of rain from September to November at many locations.

The lack of fall rain was a huge factor in the 2021 growing season. Prairie crops lacked soil moisture reserves in late June and early July, when 35 C temperatures hammered canola, oats, wheat and other crops.

Any snowfall this winter will help with soil moisture and water levels in dugouts, but snow in January is typically fluffy and contains a small amount of moisture.

“If we are receiving that dry, light… snow, it’s usually an eight to one or 10 to one reference, in terms of moisture content and snow accumulation.”

So, 30 cm of light and dry snow in January is more like three cm of moisture.

The good news is that drought conditions have become less severe, at least in the eastern Prairies.

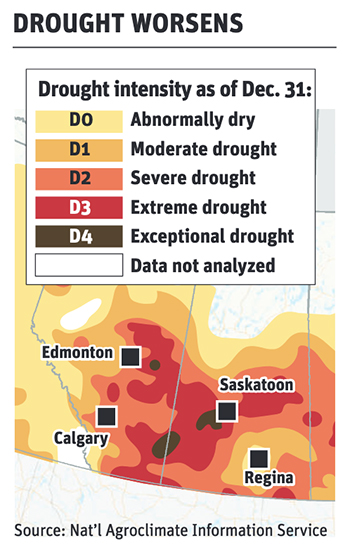

The Agriculture Canada Drought Monitor map, as of Dec. 31, shows that much of Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan is in a severe to moderate drought. That’s an improvement from last summer, when the same region was in an extreme or exceptional drought.

The huge area between Edmonton, Saskatoon and down to Swift Current, remains extremely dry.

“We haven’t seen that improvement through the central region of Alberta and the west-central region of Saskatchewan,” Hadwen said.

The winter, though, is far from over and a 30 cm dump of snow in February or March is still possible.

Ocean temperatures in the tropical parts of the Pacific have been cooler than normal, which means a La Niña is in place this winter.

“Forecasters give the December–February period a 100 percent chance of being in La Niña territory, and 95 percent likelihood for January–March,” the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said Jan. 13.

A La Niña in the Pacific affects Western Canada.

“In the prairie region, La Ninas tend to mean really cold weather and sometimes above normal snowpack,” Hadwen said.

The winter of 2022 could produce more snow than normal, which could help with dry creeks and dry soils. But most of the agricultural land on the Prairies is in a fragile state. It’s a little early to worry about weather in June, but a period of no rain in late June or early July could damage the 2022 crop.

“We don’t have that reserve (in the soil and groundwater) that we would normally have, in case of drought,” Hadwen said. “If we hit a two-week cycle of dry and warmer weather, that’s where we’ll see the vulnerability.”