WINNIPEG — If crop insurance payments to Canadian farmers were put on a line graph, from 2018 to 2022 the graph would look like a hockey stick.

Statistics Canada data shows that crop insurance gross payments were $890 million in 2018. By 2021 that figure had climbed to $3.8 billion and then hit $4.897 billion in 2022.

The large payments in 2022 may be crop insurance claims from the 2021 growing season, which were paid in 2022.

Those massive payments are connected to the severe drought of 2021, which crushed crop yields across much of Western Canada. There’s also the factor of higher prices for grains, oilseeds and pulse crops, which exacerbated the size of crop insurance payments.

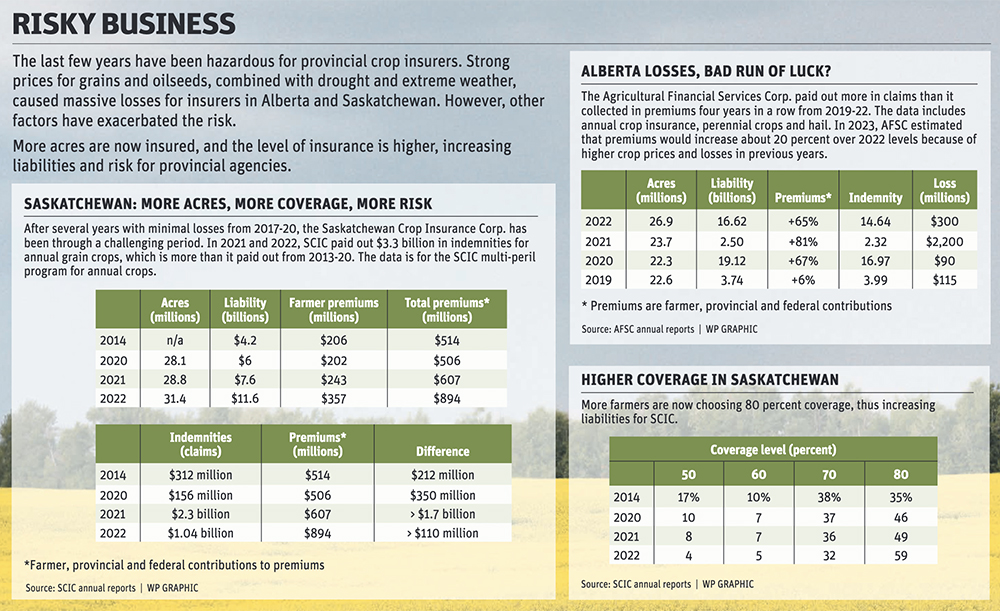

The combination of factors also caused gigantic losses for provincial crop insurers. The Agricultural Financial Services Corp. (AFSC) recorded a net loss (claims minus premiums) of $2.2 billion in 2021. The Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corp. (SCIC) reported a crop insurance loss of $1.7 billion in 2021.

A lot of the blame can be directed at the one-in-100-year drought of 2021. However, crop insurance data shows that the risk assumed by provincial crop insurers has exploded in recent years.

In 2014, SCIC had a crop insurance liability of $4.2 billion. In 2021 that figure reached $7.6 billion and in 2022 it was $11.6 billion.

The risk to SCIC was even greater in 2023 as the average coverage hit a record of $446 per acre. Assuming 31 million acres were insured, that’s a liability of $14.4 billion.

That sort of risk has triggered steep increases in crop insurance premiums for farmers and governments who subsidize crop insurance.

Douglas Hedley, a retired agricultural economist who worked for Agriculture Canada, said the drought and crop prices were obvious causes for the rise in liabilities.

But there’s more to the story.

“The third (factor) is that the West, in particular, as well as Ontario, has been moving to higher value crops,” said Hedley, who helped create the current crop insurance funding model and is a member of the Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame.

“Take a look at what’s happened in canola … and peas, beans (soybeans) and lentils…. You’re getting more dollars per acre. The moment that happens you’re getting higher crop insurance payments, particularly in drought.”

The data supports Hedley’s observation:

- In 2014, SCIC insured 8.6 million acres of canola. By 2022 the insured canola acreage was 10.6 million.

- The amount of total insured acres has also increased, going from 26.3 million in 2014 to 31.4 million across Saskatchewan in 2022.

Another factor is that farmers are choosing higher levels of coverage to protect their investment.

SCIC data indicates that 35 percent of producers selected 80 percent coverage in 2014. In 2022, almost 60 percent of growers picked 80 percent coverage.

Crop insurance payments to Saskatchewan farmers will be significant in 2023 and 2024, thanks to a drought in western Saskatchewan in 2023, the additional acres that are now insured and higher levels of coverage.

“Saskatchewan producers should receive about $2 billion in business risk management support payments this year, the provincial and federal governments said,” The Western Producer reported in November. Most of that $2 billion will be crop insurance payments.

As of November, SCIC had paid out 30 percent of claims. The forecasted payouts from the 2023 growing season could hit $1.85 billion.

Darryl Kay, AFSC chief executive officer, told DePutter Publishing earlier this year that AFSC is trying to manage the cost of crop insurance premiums.

“As many producers are aware, 2021 saw historic claim payments and that had an impact on both the insurance fund balance and individual producer’s experience, which translates into higher premiums…. We’re not trying to recover recent losses in a short period of time; rather, our premium framework takes a longer term, 25-year approach. This longer view means greater premium predictability and stability for our clients.”

Maintaining premium stability, or reducing premiums, could be tricky.

Assuming crop prices remain strong over the mid-term and extreme weather becomes more commonplace, it’s a reasonable bet that crop insurance premiums will remain high.

In Saskatchewan, total premiums at SCIC — for annual crops, forage and other insurance products — hit $1.1 billion in 2022. That’s nearly double the premiums of $576 million in 2019.

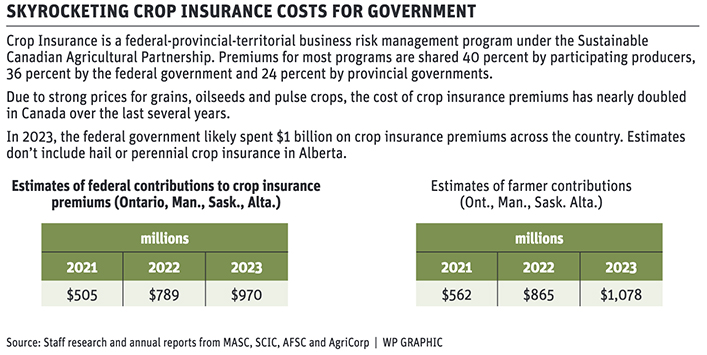

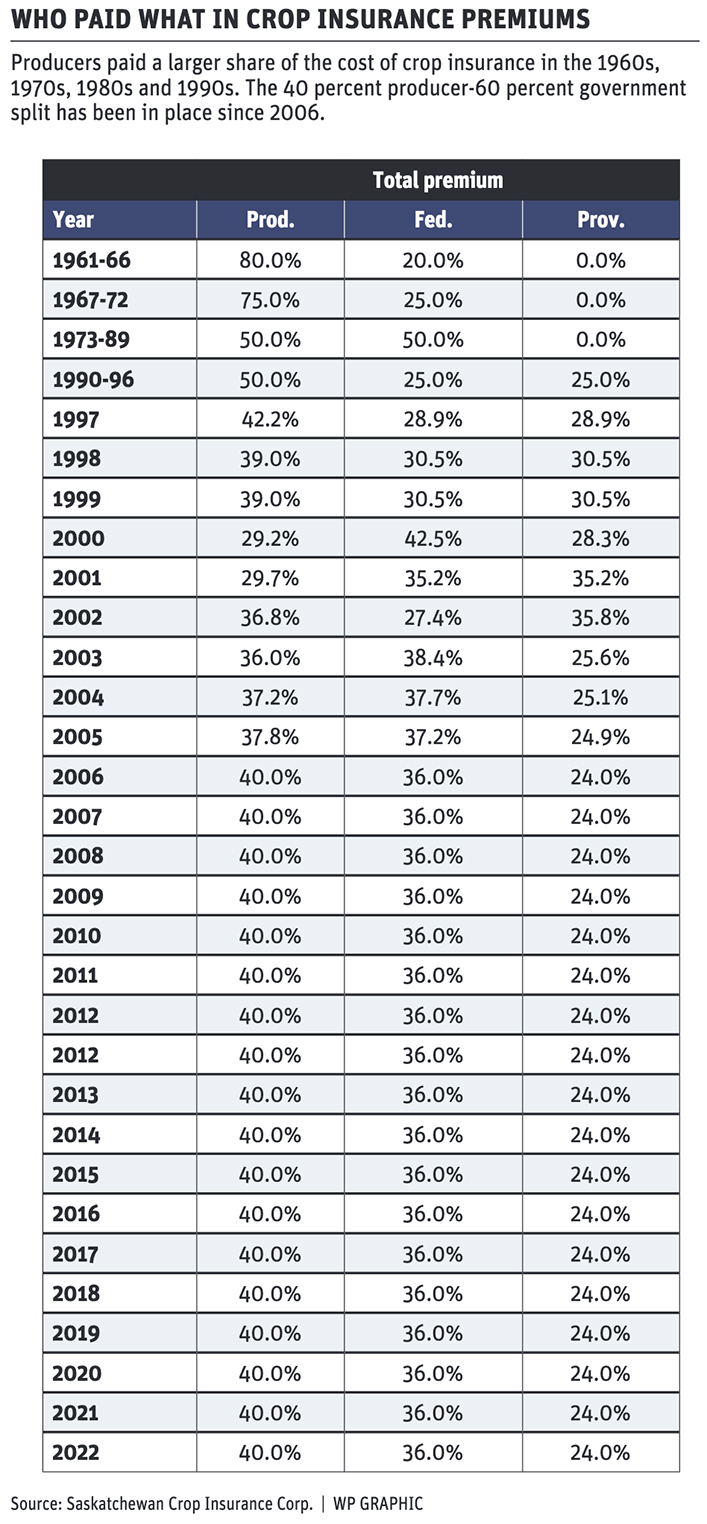

Under the current funding arrangement, farmers cover 40 percent of the cost of premiums, the province 24 percent and the feds 36 percent.

Hedley played a large role in designing this structure when he was with Agriculture Canada.

Representatives of the federal and provincial governments met in the Yukon in 2000 and hammered out the details of what would become the Whitehorse Accord.

That agreement has since evolved into the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a five year funding agreement for agriculture between provinces and the feds.

Governments agreed to the existing cost sharing structure for premiums at the Whitehorse meeting, but it wasn’t always like that.

From 1990-96, farmers covered 50 percent of the cost of premiums and the federal and provincial governments the other 50 percent.

Going back further, the provinces contributed nothing to crop insurance premiums from 1973-89. Farmers and the feds split the cost 50-50.

Farmers may be concerned about the rising cost of crop insurance, but it’s also a challenge for the feds.

It’s difficult to parse out the federal contribution in the annual reports of provincial crop insurers. However, it’s possible that the feds spent $1 billion on premiums in 2023.

Trimming that cost could be challenging, Hedley said.

“It is a beloved program, that’s pretty clear. It has been stable,” he said.

“Change is going to be difficult.”

Nonetheless, Ottawa may want to adjust the funding model, considering agriculture has changed significantly since the early 2000s.

“It’s been many years since we put it together…. That’s 20 years to have a program running,” Hedley said.

“It’s time to have a look at that program. I don’t think there’s a question there.”