The 2021 Census of Agriculture from Statistics Canada show the Prairies leading the way in agricultural production and technology.

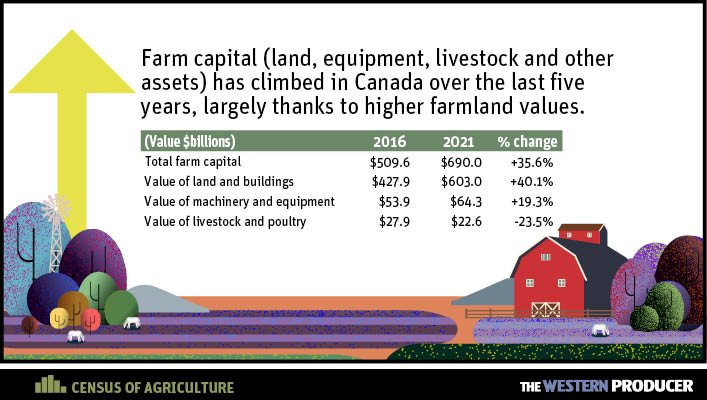

Grain production and technology use continued to rise, while livestock producers are taking a financial hit.

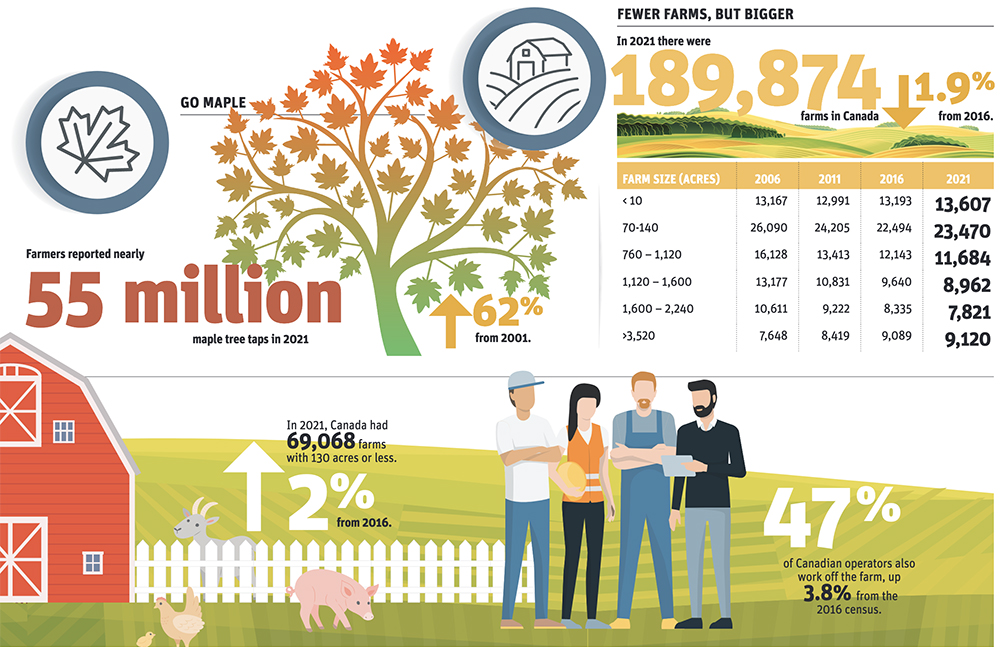

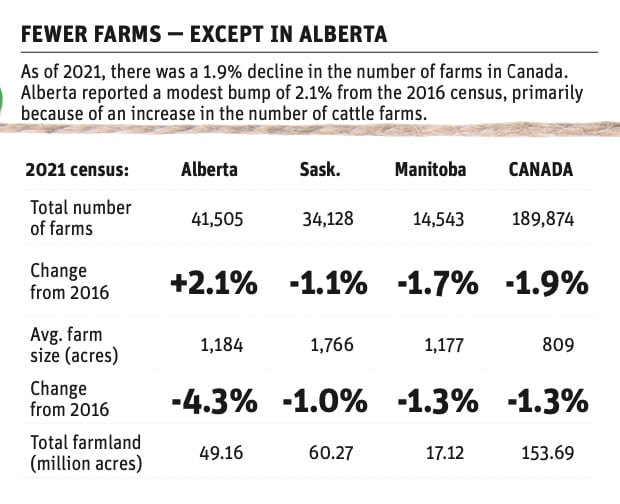

The rate of decline in the number of farms on the Prairies has slowed compared to previous census reports and less than the national average.

Alberta actually increased its number of farms. New cattle farms were the main reason for the increase. Quebec was the only other province to see an increase in farm numbers.

Read Also

Manitoba farmers fight sprouted wheat after rain

Rain in mid-September has led to wheat sprouting problems in some Manitoba farm fields.

“The key talking points are industry consolidation,” said StatsCan official Matthew Schumsky. “You’re seeing some smaller farms merge with larger farms. And that’s not unique to the agriculture sector. You’re seeing this across numerous economic sectors in Canada.”

According to Schumsky, 29.5 percent of farm operators across the Prairies are female, and 9.6 percent are younger than 35 years old. All three prairie provinces saw female operators increase by about three percent.

Alberta’s average farm operator age is 56.5 years, above the national average of 56. Saskatchewan and Manitoba farmers are younger than average, coming in at 55.8 and 54.4 years, respectively.

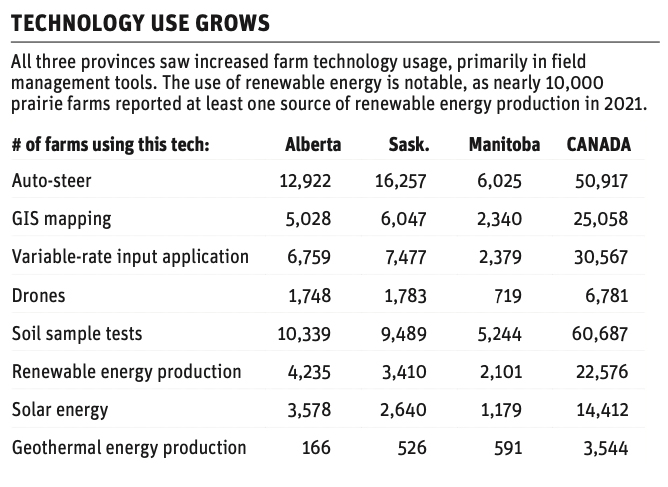

The use of agriculture technology has increased significantly since 2016.

Saskatchewan leads the way in many categories, including auto-steer, geographic information system (GIS) mapping, variable-rate input application and drone use.

“Farms are becoming more efficient, technologically savvy,” said Schumsky. “Increased technology adoption, modernization; just the premise of doing more with less.”

According to Schumsky and StatsCan, Saskatchewan probably leads in these categories because of the large amount of grain and oilseed acres, which are more likely to use the new technologies.

“I think the trends we’re seeing right now is that technology solutions are becoming more and more reliable and becoming clearer for the farmer,” said Sean O’Connor, managing director of Conexus Venture Capital and Emmertech. “They’re helping them solve some of their biggest challenges.”

Another trend was the increased use of renewable energy. Geothermal energy use in Manitoba is above the national average, and farmers across the country have been using it more.

In total, more than 9,500 farms across the Prairies reported using renewable energy sources. Alberta led the way, largely because of residents use of solar energy.

Drone use is also becoming more popular among farmers. Saskatchewan led slightly in that category, ahead of Alberta.

“Farmers are great stewards of their lands and have been for generations here in Canada,” said O’Connor.

“Now they’re being given all these exciting pieces of equipment, of technology, allowing them to increase or maintain their yields while reducing the inputs required, which is going to have a wonderful impact on the environment.”

O’Connor said Emmertech has worked with lots of farmers on technology and solutions that allow farmers to use fewer chemicals, fertilizer and other inputs.

“I think where Canada is really leading the pack and doing a wonderful job is incentivizing the creation of those technologies, so that you’re building technology and products that don’t need to be incentivized to be taken on,” said O’Connor.

“They’re taken on purely because they make business sense for the farmer.”

The future of agricultural technology will look different, according to O’Connor. Autonomous machines are starting to implement the technology on the farm.

“Over 100 years, we’ve been building our innovation in the machinery space to really be focused on, how do we get the most out of the person operating the machine,” said O’Connor. “They’re now saying, ‘how do we optimize, so that if any one singular piece of equipment goes down, the whole farm isn’t stopped?’

“Why not have small swarms of machinery on the farm that can serve various purposes, and if any one of them goes down the farm can still be highly operational while the farmer fixes the solution.”

Farmers across the Prairies continue to be world leaders in crop production.

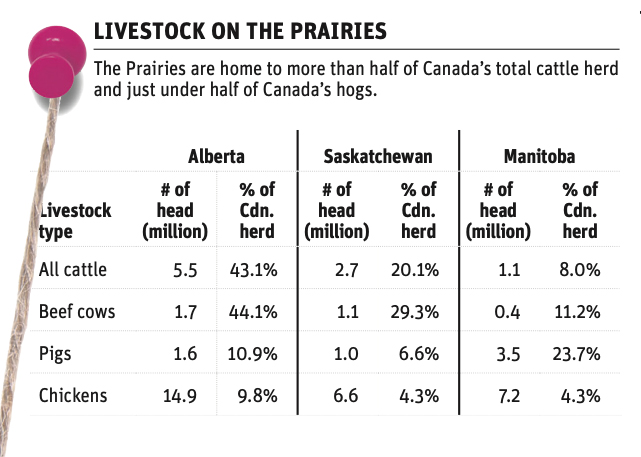

More than four-fifths of farmland in Canada is found within Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. More than 99 percent of all canola acres in Canada are found on the Prairies.

Alberta and Saskatchewan continue to produce large numbers of canola, spring wheat, barley, oats and peas. Saskatchewan accounts for almost all of Canada’s lentil, durum wheat and flaxseed production.

Manitoba also seeds a large share of Canada’s canola and spring wheat acres, and has 90 percent of the nation’s sunflower, dry white bean and soybean acres.

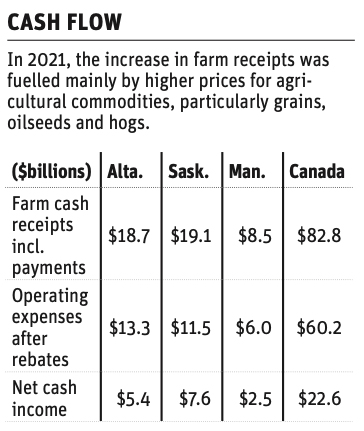

With half of the Prairies in drought and the other half under-water, grain and oilseed total revenues still managed to be the highest for all three provinces, higher than beef farming/feedlot and other agricultural revenue streams.

“I think last year, price increases, even with the impacts of the drought, I think grain producers aren’t in (too bad of shape,)” said Agricultural Producers Association of Saskatchewan president Ian Boxall. “We had a bad year last year on yield, but thank God the prices were where they are.”

As frustrating weather continues for many grain producers this year, Boxall believes crop production trends will continue and programs like crop insurance will make sure farmers stay on their feet.

“We’re here another year and we got the crop in the ground a little late, but it’s in and we’ll get it off,” said Boxall. “I think grain farmers have proper support.”

Manitoba farms manage to generate the highest average revenue per farm, while having the lowest average acres per farm. This is largely because of large pig barns and a large number of farms earning more than $1 million gross revenue each year.

Saskatchewan’s farms have an average of 500 acres more per farm than the other provinces, but generate the least amount of average revenue.

While grain commodity prices have risen substantially the past two years, livestock prices have struggled with inflation hitting new peaks.

According to the 2021 ag census, beef farms and feedlots in all three prairie provinces reported worse expense-to-revenue percentages than grain.

Boxall said livestock producers need more social security for times when the land is mired in drought, feed prices are high and cattle prices are low.

“It’s been one huge issue that is really, truly hurting the livestock sector,” said Boxall. “It’s tough for producers. We have seen the price of livestock down to levels we saw back in (2004-05).

“And yet what consumers are paying today at the grocery store is record high. So, somewhere in between what the producers are getting paid and what the consumers are paying, there is a lot of money being made by somebody other than the producer.”

Rising expenses, the rate of inflation and higher taxes from the federal government, including the carbon tax, are concerning, according to Saskatchewan Cattlemen’s Association chair Arnold Balicki.

“Prices for a cow-calf producer at the farmgate have been stagnant since 2015, and input costs, especially in the last six to 10 months, have escalated beyond anyone’s imagination,” said Balicki.

“And the carbon taxes our feds want to keep putting on us isn’t helping either… as primary porducers we have no one to slide that back down to like everybody else. We’re at the bottom of the barrel, so we absorb every increase in the cost of production.”

According to Statistica.com, one kilogram of ground beef costs an average of $12.06 as of Dec. 2021. According to SelinaWamuchi.com, the average price per kg of live cattle is $1.59.

“We need to ensure we have sustainability in our livestock sector,” said Boxall. “Currently, we don’t have that. You add in these droughts, add in the high costs of feed, the shortage of feed and shortage of water, there’s some huge concerns.”

The 2021 ag census shows concerning numbers regarding livestock acres between Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Since the 2016 census, tame and natural pasture numbers have dwindled. Reported livestock acres for cattle, pigs, chickens and sheep have all significantly fallen.

For John Wilmshurst, native grassland conservation manager for the Canadian Wildlife Federation, this has been a concern for some time.

“It’s pretty clear that grasslands are declining,” said Wilmshurst. “There’s an effort to try to monitor that using a number of techniques and one of them is the census. So, I suspect this is a real phenomenon.”

Natural and tame grasslands are home to a variety of species and organisms and the amount of carbon the grasslands pull from the air is substantial.

“It’s a huge concern,” said Wilmshurst. “The fact that native grasslands are disappearing … Once you break it, it’s broken, and then it’s gone and will take decades for it to recover to a state where you would consider it native again.”

Farmers and ranchers aren’t the only cause for the grasslands disappearing. Encroachment by brushland, natural resource development and urban development are causes.

However, the conversion of native grasslands to row crops is the largest contributor.

“I suspect the pattern that you’re quoting is something that’s been going on for longer than since 2016. I bet if we go back, that decline has been happening for decades,” said Wilmshurst.

He said financial incentives may be necessary for farmers to maintain the grasslands.

As cattle and livestock prices struggle to compete with the rate of inflation, farmers and ranchers have been finding more value converting grasslands to cropland. Pastureland decreased in all three prairie provinces, while cropland increased.

“We’re seeding more acres for silage than we are hay production,” said Balicki.

“The production capacity of four acres is far greater than what you can get from alfalfa-grass mix.”

The financial pressure put on livestock farmers in recent years, coupled with rising grain and oilseed prices, make the decision to convert pasture to cropland an easy one.

“The economics change all the time,” said Wilmshurst. “Right now, if you’ve got land you can turn into crop, it’s likely to make a pretty good return on it given the world economic situation.”

Livestock producers have traditionally worked with the environment to protect grasslands and the species living on them. But with the recent drought slowing grass growth, alternatives have become necessary.

“They’ve finally come to the realization that those cattle producers with their grasslands are doing a lot of good for sequestering carbon and providing habitat for wildlife and species at risk,” said Balicki.

“But just patting us on the back doesn’t put any money in our back pocket.”