WINNIPEG — Georgia is famous for peaches; northern Ontario is not.

That climate reality, however, didn’t stop a determined gardener from trying to grow peaches in Sault. Ste. Marie, Ont.

“There was an old Italian guy (who) grew a peach tree for a few years, and it eventually bore fruit,” said Dan McKenney, a research scientist with the Canadian Forest Service in Sault. Ste. Marie.

Read Also

Saskatchewan project sees intercrop, cover crop benefit

An Indigenous-led Living Lab has been researching regenerative techniques is encouraging producers to consider incorporating intercrops and cover crops with their rotations.

The old guy and his peaches made it into the local newspaper, but eventually, old man winter had the final say in the matter.

There was a hard winter, and that was it for the peach tree, said McKenney, who is part of a federal government team that creates plant hardiness zones for Canada.

The latest update to the zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

The recent information shows that most regions of Canada are warmer when compared to the 1950s and 1960s. Not warm enough for peaches in Sault. Ste. Marie, but definitely warmer.

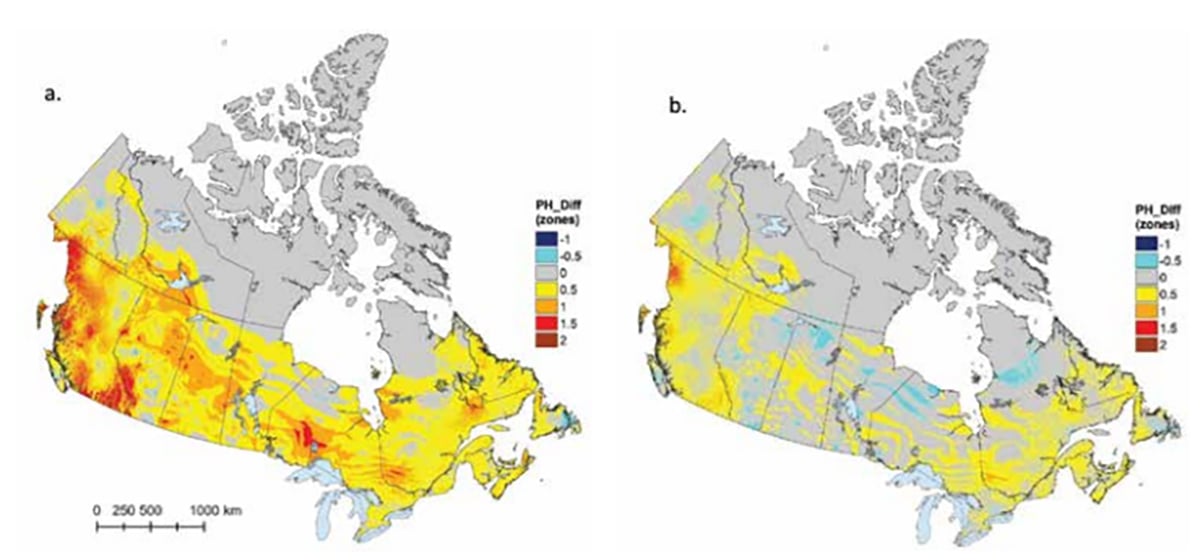

“Canada’s climate has changed significantly over the past century.… Specifically, average temperatures have increased by approximately 1 to 3 C across the country since the middle of last century,” says a report published in Nature Scientific Reports, called Updated Plant Hardiness Zones for Canada.

“These changes have significant implications for plant growth and survival across the country.”

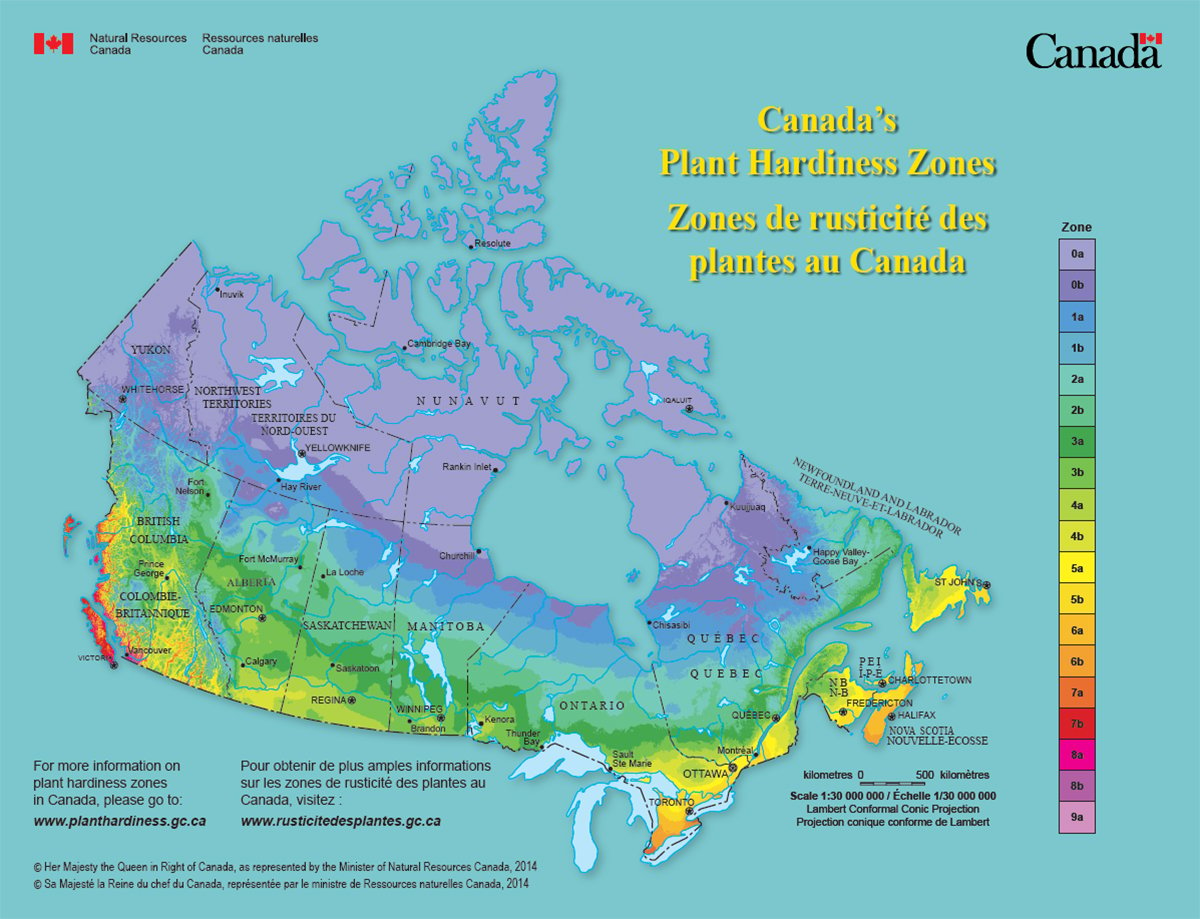

Federal employees who are part of the Canadian Forest Service have also created a website called www.planthardiness.gc.ca.

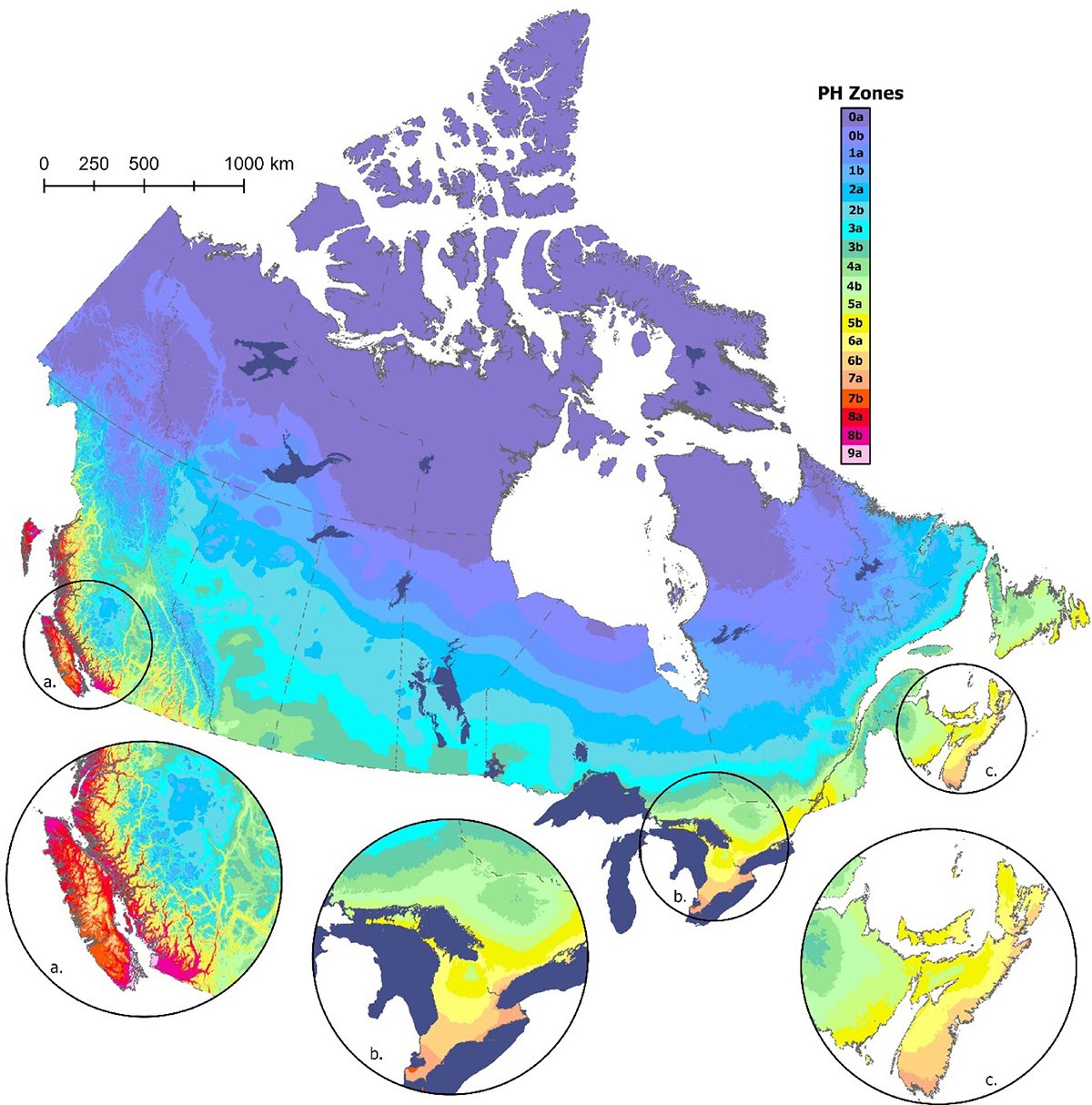

It contains updated maps with new plant hardiness zones for Canada’s different regions.

The latest map, for the period from 1991-2020, shows that growing conditions have changed since the 1960s.

“Relative to the 1961–1990 period, much of southern Canada has experienced an increase in Canadian hardiness zone ratings, with the largest increases (up to two full zones) happening in Western Canada, particularly in southern and northwestern British Columbia,” says the Scientific Reports article.

The changes don’t mean that a gardener in Medicine Hat, Alta. can grow tropical orchids in their backyard, but a plant species that historically hasn’t been grown around Medicine Hat might now work in that city.

“(Gardeners should) check out their new zone at that website, see if their zone has changed,” said John Pedlar of the Canadian Forest Service, part of the team that updated the plant hardiness zones.

“Then, make sure the plant they’re choosing from the store … falls within their zone. Then do some experimentation from there.”

The plant hardiness zone website also has a tool in which a gardener can enter the name of a plant species and determine where it can be grown in Canada.

“It’s best if people know the scientific name (of the species),” McKenney said.

He added that the plant hardiness zones and the related maps were designed for gardeners and not commercial farmers.

“We’re not Ag Canada,” he said.

“People need to look closely at what they use these things for.”

The plant hardiness maps represent a long-term trend, but the weather in a particular year can still diverge from that trend.

As an example of the risk, a farmer in southern Manitoba may want to experiment with a commercial crop of peppers because the local climate has been getting warmer. However, if the spring of 2026 is bitterly cold, that experiment could be a financial disaster.

“Gardeners may be willing to take the risk … they love that stuff. They love to push the envelope,” McKenney said.

“But for people who are in it for their livelihood, you’ve got to be darn careful about the decisions you make.”

That said, there is evidence that warmer temperatures are changing where commercial crops are grown in Canada.

There was a time when vineyards only existed in the Niagara region of southern Ontario. Now, commercial wineries are growing grapes north of Toronto.

“The harvested area of grapes in Ontario has increased by approximately 25 per cent over the 1990-2020 period, with production expanding to the north,” says the Scientific Reports article.

Gardeners across Canada can now experiment with new varieties of flowers and plants, thanks to the warming temperatures. However, they shouldn’t push the envelope too far.

Regina is still a cold place to live, even if its plant hardiness zone has slightly changed.

If avid gardeners really want to grow some exotic plants, they should move to Vancouver Island.

The least common hardiness zone in Canada is 9a, which is found at the southern end of Vancouver Island, around the city of Victoria.