Perseverance is a great quality. But farming is now a high-stakes game, and market conditions can change so quickly that sticking to an outdated business plan can be fatal.

So how do you know when it’s time to toss what was working and head in a brand new direction?

The story of Kumaran Thillainadarajah offers a valuable lesson.

Six years ago, the native of Sri Lanka made a breakthrough discovery as a student working for the summer at the University of New Brunswick. His project was making a covering for prosthetics out of carbon nanotubes, one of the strongest materials ever created.

Read Also

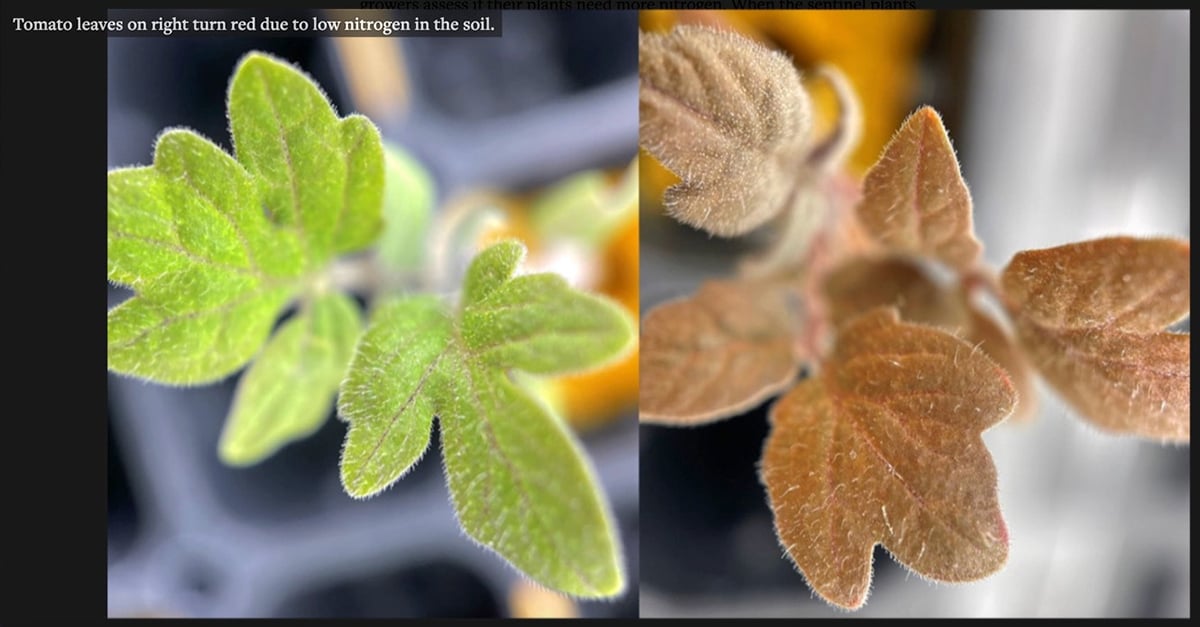

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

“Because my background is in computer engineering, I was much more interested in the electrical properties of this nanomaterial,” says the 28-year-old.

“So what we did was make this skin-like polymer that could also be used as a (pressure) sensor.”

This was a very big deal. Your skin’s ability to sense pressure is what allows you to shake someone’s hand without crushing it, and tell the difference between silk and sandpaper. So Thillainadarajah founded Smart Skin Technologies at www.smartskintech.com.

Fame and fortune seemed just around the corner.

Cut to today. Smart Skin is one of the hottest tech start-ups in Canada, and recently attracted $3.9 million in venture capital funding. But it has not revolutionized the development of artificial limbs. Instead, its technology is being used to reduce breakage on bottling lines.

And that dramatic shift didn’t take place because Thillainadarajah lacked perseverance.

“It was a tough pill to swallow,” he says. “It was really my coaches and mentors saying, ‘this is not a market for a start-up company.’ Part of me really wanted to prove them wrong because I really believe in this technology.”

Nevertheless, he switched gears and found a new use for his wonder material, a touch-sensitive case for smartphones. It was another great idea — you not only could make the back of a phone as touch sensitive as the screen, but allow the device to know how hard you were pressing. This took point-and-click to a whole new level.

“We were talking to Samsung, Nokia, Microsoft, all the big companies,” he says. “We spent a year pursuing this market before we learned what seems like a simple lesson: customers are people who pay for your product, and are not just interested in it, … but no one was willing to put down money.”

Fortunately, an entirely different business sector was. One day Thillainadarajah got a call asking if his product could be adapted for a bottling line in a brewery. Turns out that even though the lines are highly engineered and constantly re-calibrated, about one in 200 bottles breaks as it is being cleaned, filled, capped or packed.

“That may sound like a small number, but it translates into millions of dollars and every bottling plant in the world has this problem.”

So Thillainadarajah and his team created the Quantifeel DRONE. The cylindrical device, which has up to 1,000 pressure sensors and wirelessly transmits data in real time, allows someone overseeing a bottling line to know instantly when and where a problem is occurring.

The device reduces breakage by nearly 90 percent and is now used by virtually all of the world’s major beer-makers.

“When you’re solving a problem, then people will pay for your product,” notes Thillainadarajah.

Prosthetics to smartphones to beer bottles. Quite the change.

But it was driven by business fundamentals. The first was having — and constantly revising — a business plan. As he studies computer engineering and nanotechnology, Thill-ainadarajah also took business courses and learned how to create income projections.

And when he launched his company, he sought out mentors. They kept pointing out the lengthy testing period for medical devices meant years of high expenses and little income, and that phone-makers were offering praise but not contracts.

Launching a start-up is a perilous undertaking, but so is buying farmland, expanding production and investing in the latest farm equipment. What made sense five years, or even five months, ago could be a huge mistake now.

A regularly updated business plan will give you the numbers, and experienced advisors who aren’t afraid to speak plainly can tell you if those numbers are realistic.

It doesn’t matter whether your business is nanotechnology, crops, or livestock — the future belongs to those who plan for it.