A former hog farmer says he has a solution to prevent producers from drowning in a manure cesspool.

“In 20 years, I’ve fallen in manure, been sprayed by it and definitely smelled it. I have a pretty darned good idea of manure,” said Don Gregorwich, environmental operations manager for Gem Manufacturing Ltd.’s agriculture division.

“On our farm we had a good system of manure management, but there were times it seemed the manure handled us.”

Last July Gregorwich, who lives near Kelsey, Alta., got out of hogs to sell farmers and livestock managers on the idea of buying a bacteria that breaks down fecal solids and reduces odor components called amines.

Read Also

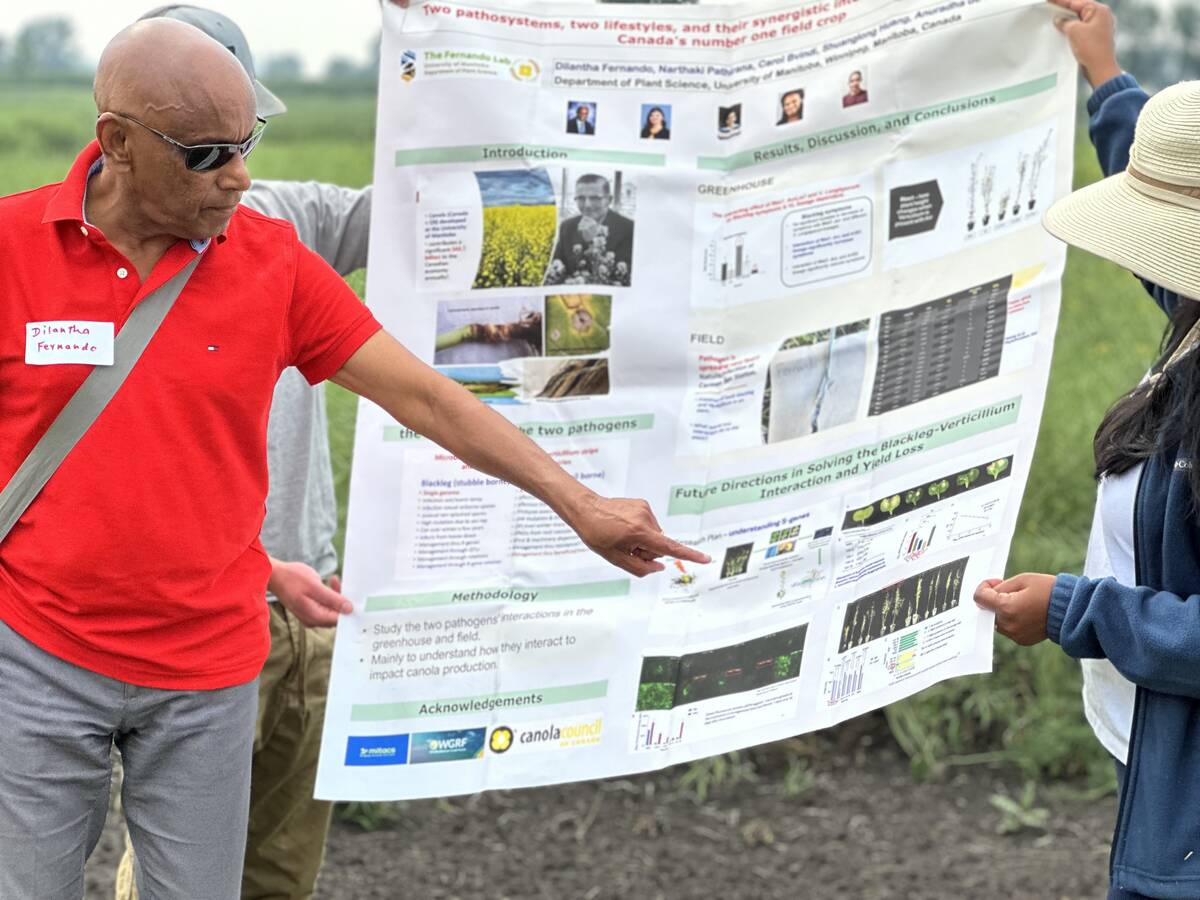

Verticillium may undermine canola blackleg resistance

University of Manitoba research finds verticillium stripe in canola can break down blackleg resistance, creating challenges for disease management and yield protection on the Prairies.

With a sharpened pencil tucked behind his ear, Gregorwich, surrounded by filled jars, bottles and zip-lock bags in his farm office, explained the bacteria works largely like instant coffee.

To activate the manure-eating particles that are dried onto crushed peanut shells, a producer pours them into a pail of lukewarm water. In about half an hour the bacteria are ready to hunt for food and the producer sprays the material on the barn floor or dumps it in a manure pit. As the barn manure is flushed into a lagoon, the bacteria follow.

Gregorwich tells of one case in which a farmer planned to break through cement to open one side of a full 2.5-metre-deep manure-holding tank. Because the mess was mostly solids, the farmer planned to hire a back hoe to haul out the manure.

Instead, he bought about 5.5 kilograms of Gregorwich’s formula. In about 21Ú2 months he had almost one metre of slurry that was easier to take out.

Farmers should add new bacteria, which naturally multiply, into the pit about three times a year, said Gregorwich, adding the following two applications require a smaller dose. The bacteria cost about 40 to 50 cents a year per market hog, said Gregorwich.

The company he works for, based in British Columbia, also sells bacteria to clean oil spills and break down restaurant grease.

The technology has been around for about 20 years, but is new to Canada’s hog industry, said Gregorwich, who tried it on his own barn before selling his hogs.

“It reduces the solids dramatically,” he said.

John Patience of the Prairie Swine Centre in Saskatoon said producers should look for solid scientific information when investigating products like Gregorwich’s.

“There’s literally dozens and dozens of those products,” said Patience, referring to manure additives. “It’s very, very difficult to evaluate at the farm level.”

He’s not familiar with Gregorwich’s product, but the centre is evaluating three similar projects in its barns and those studies should be out in a few months.

Generally, accurate information on pit additives is hard to come by, he said.

There is some skepticism over products like his, admitted Gregorwich, who added detailed information is available through his company.

“North Americans seem to have the preconception that you have to have a complicated system instead of bacteria that you can’t even see working.

“But Mother Nature hasn’t been using trackers and backhoes and heavy equipment to clean up the environment.”