Work will still happen during the COVID-19 crisis, but important nuances may be lost without face-to-face interactions

Relations between farmers and agronomists will likely look different in the coming months if people are told to keep visits at bay.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already got crop specialists thinking about how they plan on advising farmers once the growing season is underway.

Field work can still happen, but it’ll likely look more digital. After specialists scout, conversations about their findings will likely occur via phone, teleconference, text message, email or smartphone app.

“Given the social distancing requirements and challenges, I suspect for the time being that physical face-to-face meetings will be more limited,” said David Lloyd, the CEO and registrar with the Alberta Institute of Agrologists.

Read Also

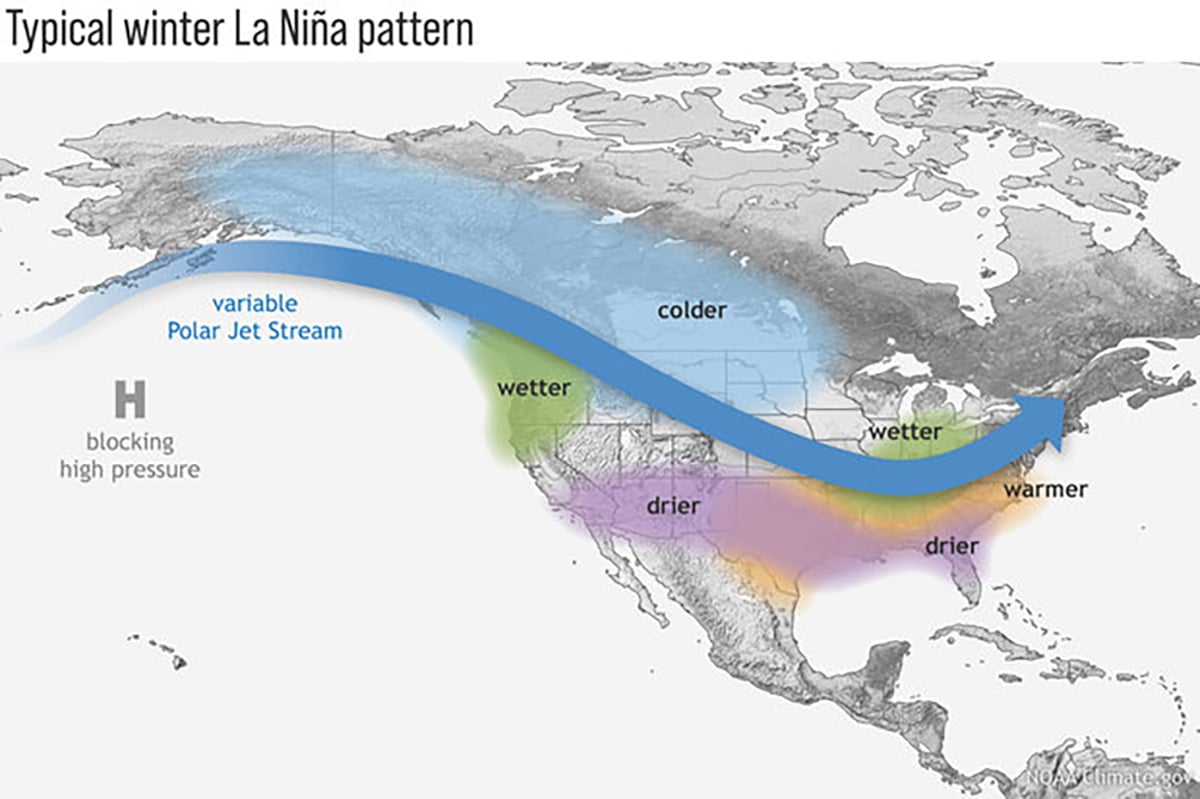

Weather factors to watch this winter

There are currently three main factors that could be a driving force behind the type of weather we may see this winter. The first is La Nina, which is currently in a weak stage.

“Much of the professional support offered by our members will continue, even field activity on the farm,” he said.

Jeremy Boychyn, an agronomy research extension specialist with the Alberta barley and wheat commissions, said relationships between farmers and agronomists will range.

He said those who are used to working online or with smartphone applications might not change much. For those who are used to in-person meetings, they may have to get used to more phone calls, text messages and photo-sharing.

“For those who might have challenges with technology, those discussions are going to need to be had beforehand,” he said. “It’ll help producers and agronomists get an idea of what the expectations are moving forward.”

Boychyn said for him, it’ll be a transition to have fewer face-to-face interactions.

Even though he is tech-savvy, he said he appreciates in-person conversations. They help producers and agronomists talk thoroughly with one another when addressing crop management.

“I do go out when there are crop challenges, and I work with a few producers who call me when they see issues, so I’m really going to have to make sure that, when I transfer information to them, there isn’t a loss of translation,” he said.

Clint Jurke, the agronomy director with the Canola Council of Canada, said agronomists will have to interact differently. What that looks like has yet to be determined, though it’ll be more electronic.

“Farmers still need to be out in the field and agronomists will be walking them, but they will likely not be walking close together at the same time,” he said.

He said without face-to-face meetings, it’s important people learn to be effective when communicating digitally. Crop tours may happen online and webinars may become more common.

However, he said, learning happens when people get up close and personal.

“That physical interaction with the plant at the time of teaching, that’s something we’re going to lose, but I believe we can offer that nuance in a virtual format,” he said. “It’s going to take more work.”

Robert Saik, founder and board chair of AGvisorPRO, an online tool that connects producers and advisors digitally, said it will be helpful when people can’t connect face-to-face. It lets farmers seek advice from other farmers or crop specialists.

He said the organization has long been sensing a need for more digital connection in the agriculture industry between specialists and farmers, but the pandemic has elevated that need.

“This transition to more technology was going to happen anyway,” he said. “It doesn’t make sense to put advisers on airplanes and into rental cars to drive to halls or fields. A lot of this coaching work can be done remotely.”

Still, some things get lost when there aren’t face-to-face interactions.

Boychyn said the nuances come out when in-person conversations happen. Information could get missed if it’s compiled in an email or text message, he said.

“The time made for those discussions is where the relationship building happens, and where the nuances of management are discussed,” he said. “It’s where there might be opportunities for different management decisions to find room to grow from.”

As well, even though farmers have their family, rural places are isolating, he said. An agronomist might be a farmer’s only contact that helps him or her move through the season.

“There is a gap there, as well, that should be considered by agronomists and producers as we move forward in this challenging time,” he said.