Beneath the daily cacophony of tariffs, politics and extreme weather, cyclic market swings quietly exert more impact on farmers’ bottom lines than any of the media noise.

The big commodity markets of the free world can be likened to a pendulum. They swing far in one direction until natural forces cause them to lose momentum and swing far in the opposite direction.

Commodities swing from expensive to cheap and then back to expensive. When they’re low-priced relative to production costs and cheap for users, less will be produced and more will be used, prompting an upswing. When they become high-priced relative to production costs and expensive for users, production will increase and less will be used, triggering a swing back down.

Read Also

U.S. soy subsidies will cause lasting damage to industry

Nothing illustrates the demise of world trade agreements more than the recent dispute between the United States and China.

It can be profitable to understand where the crop markets are positioned in the context of their big-picture cycles.

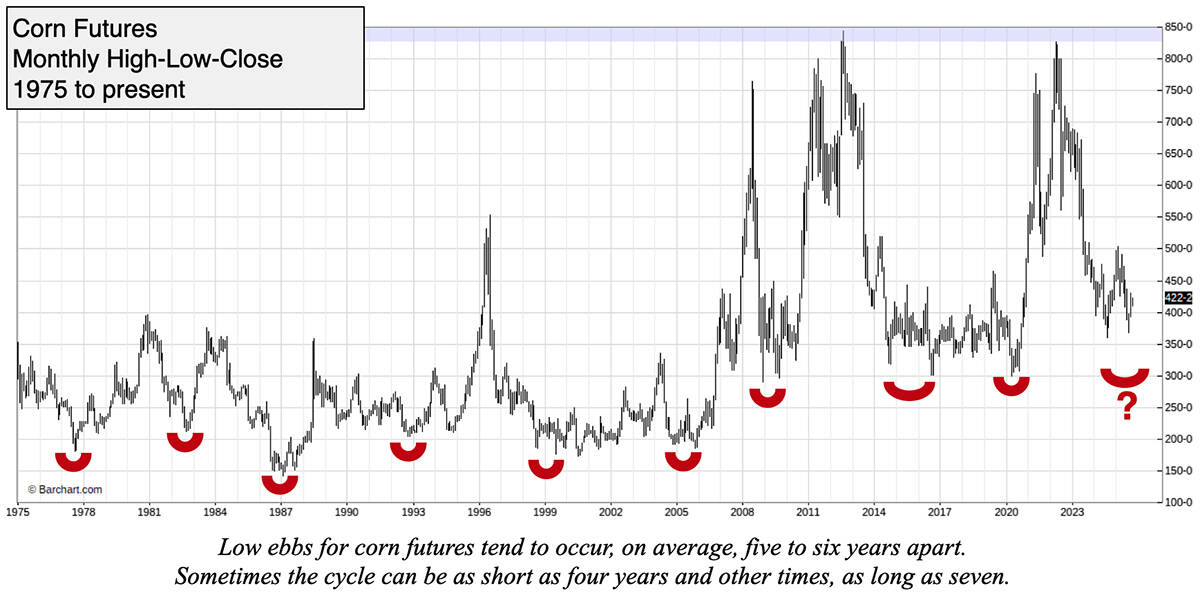

Corn: on the doorstep of a cyclic low

The primary corn market cycle, documented for more than 150 years, has a five to six-year swing from low to low.

At times clear and other times unclear, this pattern has sometimes been compressed into four years and sometimes lengthened to seven. However, it remains a useful analytical tool.

Usually, after forming a major cyclic low, corn futures will rally at least 50 per cent before hitting a cyclic high. More commonly, the price will more than double.

During the bottoming process, the market will sometimes strike an initial low, bounce sharply and then retreat to the vicinity of the earlier low. This can form what chartists call a “double-bottom.”

Let’s check the last four lows for this cycle:

- Double bottom in 2004 and 2005, at slightly under US$2 per bushel

- Late 2008 with a test in 2009, at slightly under $3

- 2016 at approximately $3

- 2020 at approximately $3

Where are we now?

About five years from the last cyclic low, the market has entered a window for another low.

However, before the low can fully form, there is work to be done. A massive surplus must be worked down.

The U.S. supply at harvest — including production plus carry-in from the previous marketing year — will exceed 18.1 billion bu. This eclipses last year’s supply of about 16.7 billion and is far above the total supply at the last three cycle lows. Odds are the market has some more dips ahead of it, as the low is slowly formed.

Markets can be surprising. We might look back to see that the market bottomed in the US$3.50 area. However, a slide toward $3 sometime in the coming year is more likely.

Conclusion: Be prepared to endure more low prices before riding the next profit wave.

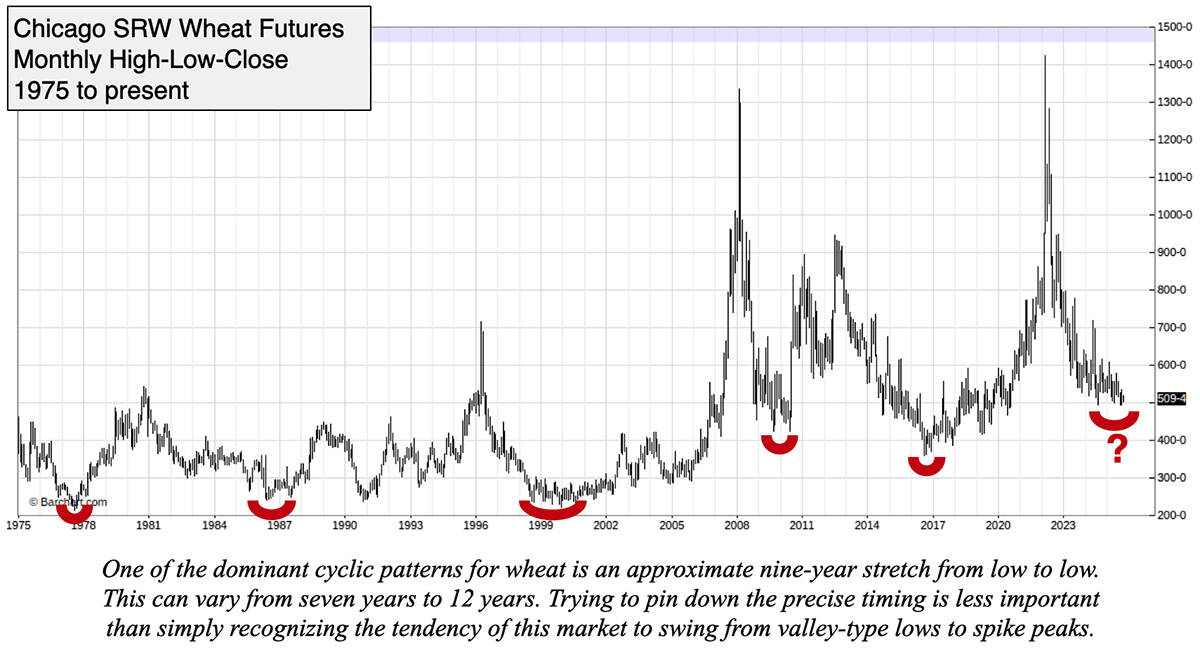

Wheat: trudging through valley floor

For more than 200 years, wheat has exhibited an approximate nine-year cycle from low to low. Sometimes a 4.5-year swing has emerged within this larger cycle. As with corn, the clarity of the nine-year pattern for wheat comes and goes.

It’s common for the prices at the major cyclic highs to be more than double the lows.

Let’s review the recent discernable lows:

- A long, slow bottoming pattern in 1999 and 2000 at under US$2.50 per bushel

- A double bottom in 2009 and 2010, around $4.20

- Major low in 2016, around $3.50

Where are we now?

Nine years after the 2016 low, a major low is due. As of press time on Oct. 8, daily futures contracts were trending down without clear bottoming signals. There were no definitive chart signals indicating the lowest prices were yet in place.

The supply is ample but not burdensome. Unlike with corn, the U.S. supply of wheat from the old-crop carry-in plus production is within the range of the past several years. It’s estimated at around 2.8 billion bu. That’s up from last year, but in line with the levels of the past three cycle lows.

Conclusions: The lowest prices on the monthly chart may occur as soon as this fall and likely by next fall. That said, upside the coming winter and spring will be limited by the heavily supplied corn market, which will be a weight on wheat’s shoulders.

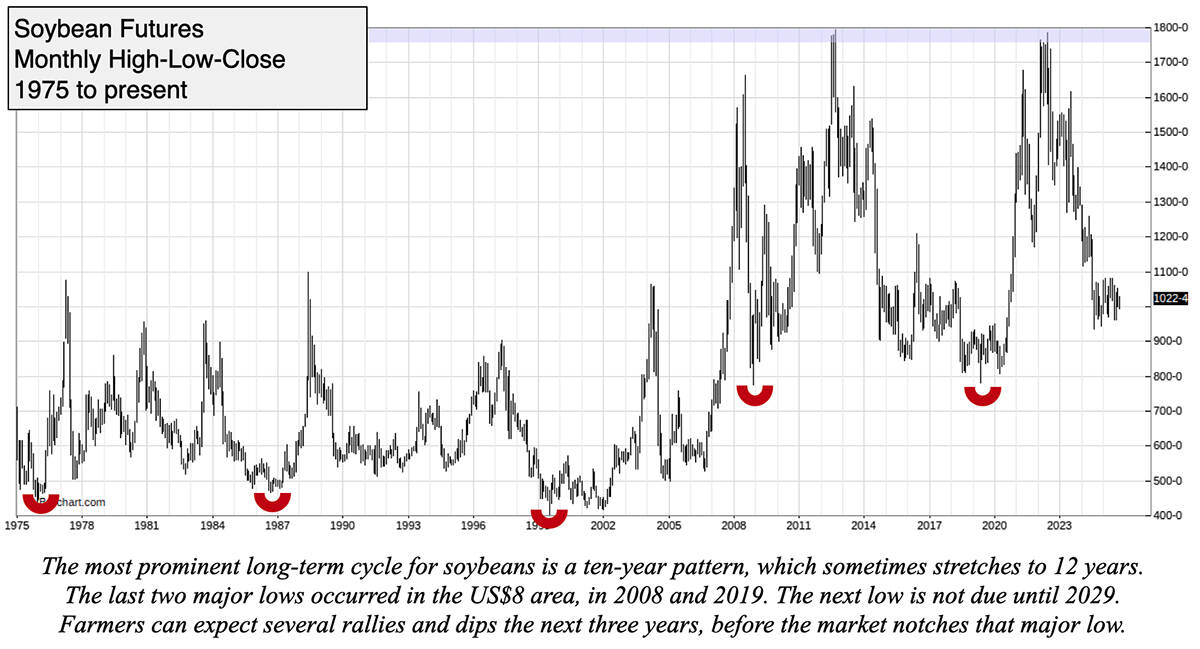

Soybeans: Less downside risk than corn

The predominant cycle for soybeans is about 10 years from low to low.

This pattern can vary from eight years to 12 years. The 10-year pattern has, at times, subdivided into two five-year cycles.

Lows for the 10-year rhythm occurred in:

- 1999, at a little above US$4 per bushel

- 2008, at under $8

- 2019, at under $8

Where are we now?

The window for the next big cycle low should open in 2029.

However, the long-term chart above displays multiple rallies between the 10-year lows. If the current cycle subdivides into its periodic five-year rhythm, then last August’s low of US$9.36 1/4 may turn out to have been the low for that cycle. As such, this market is in a position to experience solid rallies in 2026 and 2027 before retreating toward its 10-year low.

Conclusions: The U.S. soybean supply is not heavy. It is roughly 4.6 billion bu., down from last year’s 4.7 billion. In general, soybean futures will likely perform better than corn futures in the coming year.

Survival tips

Farming is a long-term business. You must survive the down cycles to reap the rewards of the up cycles. Understanding whether a market is grinding through a major bottom or experiencing a peaking phase can empower your marketing and business decisions. Maintaining faith in eventual recovery may prove helpful during these periods of low prices.

John DePutter was a commodity market adviser for over 40 years. He is a GP Principal at Ag Capital Canada and watches the markets from London, Ont.