A recent study out of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine investigated the presence of a rare parasite in elk, deer and moose from Saskatchewan.

The research, which was published in the Canadian Veterinary Journal, focused on Babesia odocoilei.

This is a microscopic parasite that most commonly infects the blood of white-tailed deer, but can also sometimes occur in other cervids such as mule deer, elk and moose. Infection has also been identified in several other wildlife species including reindeer, bighorn sheep and muskoxen.

Read Also

Beef cattle more prone to trace mineral deficiencies

The trace mineral status of our cows and calves is a significant challenge for western Canadian producers and veterinarians.

It was thought to be typically found in warmer, southern locations of the United States where ticks are common; there were no known cases in Canada before 2012.

In that year, a farmed elk near Prince Albert, Sask., was affected by the disease babesiosis, which was caused by infection with this parasite. More recently, there have been cases in elk and reindeer from Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec.

The impetus for the recent study was a case of the disease in Saskatchewan.

A female farmed elk was euthanized for severe weight loss. A veterinarian conducted an autopsy, confirming the animal had no fat stores.

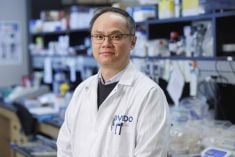

He sent samples to the Prairie Diagnostic Services laboratory in Saskatoon, where they underwent various tests.

Routine blood counts revealed that the elk was severely anemic, meaning it had very low numbers of oxygen-carrying red blood cells. This was accompanied by evidence that blood cells were rupturing, and the body was working hard to replace them.

The pathologists who examined the blood under a microscope also identified the presence of blood parasites that looked like Babesia. Molecular tests confirmed it was Babesia odocoilei.

The researchers of the recent study wanted to know if wild and farmed animals had been infected before the first known case in the province.

Using the available archives, they tested 197 samples dating between 2000 and 2014 for evidence of infection. White-tailed deer, mule deer, elk and moose were included in the study.

The results show that the infection was rare, but present in several species.

One wild white-tailed deer and one wild moose were infected. The positive moose sample was collected in 2008, representing the earliest known infection of this parasite in the province and the first documented infection in a moose.

There was also one farmed elk that tested positive for the parasite in the study. The cases were found near Humboldt, Sask.

It isn’t clear how these animals are getting infected. The main tick thought to spread the micro-organism south of the border isn’t established on the Prairies. When a tick of this species is recovered, it is assumed it came on a migratory bird from the south, since they can’t reproduce here given our long, harsh winters. It is possible one of the clandestine ticks brought the parasite with it. Another possibility is that ticks found more commonly in Saskatchewan, such as the winter tick, were spreading the disease.

While we aren’t sure how it is spread here, we do know that severe disease related to infection is likely to be rare. Most infected animals have no clinical signs associated with infection. Only rarely do individuals develop the anemia and emaciation that can lead to death or euthanasia. Severe disease seems to occur following severe stress or in animals that have never been exposed to the parasite before.

Unlike chronic wasting disease, which is having an impact on the health and population levels of deer and other cervids in the province, it is unlikely that babesiosis will have the same effects.