OLDS, Alta. – When rancher Paul Froehler decided to try his hand in the beef business instead of finding an off-farm job, he soon learned the pitfalls.

“Value-added is a hard way to make money,” he said.

He operates the Canadian Celtic Cattle Company, in which he and partners raise beef from Highland, Galloway and Welsh Black cattle. Formed in 1997, the company has managed to crack the high-end restaurant trade in Calgary.

It all started when the former Limousin breeder bought a 300 pound Highland heifer at an auction. The resulting calves produced quality meat and he decided he had to find more Scottish type cattle.

Read Also

Pork sector targets sustainability

Manitoba Pork has a new guiding document, entitled Building a Sustainable Future, outlining its sustainability goals for the years to come.

He found a Galloway bull and eventually added Welsh Black to the crossbreeding program at his place near Strome, southeast of Camrose.

Besides good beef, he wanted hardy cattle with good hair coats to help them survive five months of winter. He also wanted smaller-framed cattle than his commercial Limousin cows and found the Scottish cattle crosses gave him a blockier, smaller animal with a docile temperament.

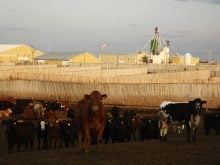

He keeps about 250 commercial cows and 800 backgrounders.

Working mainly with two other producers, Randy Kaiser and Scott Campbell, the cattle are raised hormone free and must go through a preweaning immunization program to avoid using antibiotics later. They receive a diet high in roughage to encourage the production of omega 3 fatty acids in the muscle.

After getting the animals and feed regimes in place, Froehler then has the challenge of trying to sell what he considered a premium product.

“We all know how to grow excellent beef but we have to go beyond that,” he said at a cattle producers’ seminar in Olds.

“I’m done producing for utility eaters. I’m only going to produce food for people who can afford to pay money and cover my costs of production with some profit.”

He teamed with Calgary-based food wholesaler, Wally Foremsky and his company called Community Foods.

With 30 years of experience in the food business, Foremsky knew what he was doing when it came to supplying a premium product to the discerning consumer.

First, Foremsky had to learn to meet demand every week with a consistent product.

Between 10 and 15 head are processed weekly at a provincial plant in Strathmore, Alta., but if they want the business to expand they must find a federally inspected plant.

Rancher’s Beef near Calgary has agreed to work with them but Foremsky must buy enough volume to make it work for the slaughter company.

Getting their meat to market has never been an easy sell.

The National Hockey League strike cut sales back 25 percent because fewer people were going to restaurants carrying their beef. Beef surpluses caused by the BSE trade embargo created other problems.

“We started just before BSE, which was not great timing and we have the same problem every packer in the world has,” said Froemsky.

They can sell the top-end cuts but the rest remains harder to move. The hips, chucks and trim are widely available.

They have developed a hamburger patty market, sold to a seafood restaurant in Calgary. They also opened a meat market called Second to None Meats in downtown Calgary offering natural beef and an array of other naturally raised meat products.

For Foremsky, the Celtic Meats company covers about 10 percent of his sales. He also sells elk, organic chicken and other food products so customers receive a wide selection of products.

“If we were just selling natural beef we would be gone,” he said.

Embarking on this kind of marketing journey calls for tenacity and an understanding of how to give customers a consistent product when they want and on time.

This business offers only one chance to meet commitments and if suppliers do not deliver, they lose the contract. It takes years, not months to develop a business and make an impact in the market.

“It is one person at a time,” Foremsky said.