Targeted deworming in small ruminants starts with the right animal, accurate dosing and smart timing.

That was the message at a fecal egg count workshop hosted in Ontario by that province’s sheep association in June.

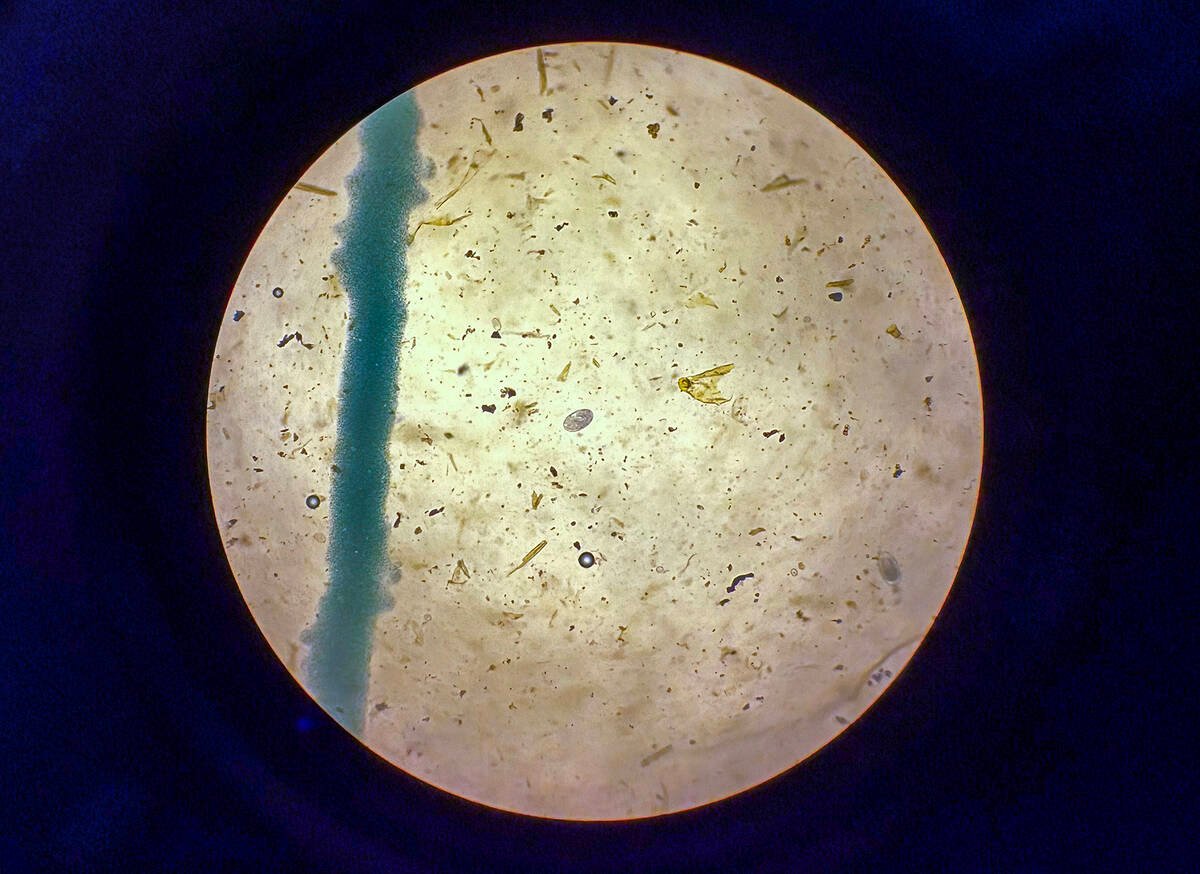

Dr. Brad DeWolf, a veterinarian, and Victoria Allcock, a master’s student at theUniversity of Guelph, are researching parasite control in small ruminants. They led 12 sheep and goat producers through the hands-on workshop, covering Modified McMaster fecal egg count (FEC) training, parasite identification and tools essential for reducing parasite loads.

Read Also

Saskatchewan Cattle Association struggles with lower marketings

This year’s change in the provincial checkoff has allowed the Saskatchewan Cattle Association to breathe a little easier when it comes to finances.

“There’s not going to be a magic bullet,” said DeWolf, adding long-term sustainable parasite management requires a combination of strategies, including FECs to maximize dewormer benefit and slow resistance.

The workshop focused on identifying two major parasite types in sheep and goats:

Gastrointestinal nematodes such as Haemonchus (barber pole worm) and Trichostrongylus, which live in the digestive system and cause disease.

Coccidia, which typically affect lambs and leads to diarrhea and impaired growth performance.

“It’s no surprise parasites are costing every sheep producer money to somedegree,” DeWolf said, whether that’s due to drug costs for deworming or animal deaths.

Canada hasn’t reached the dewormer resistance levels encountered in NewZealand, but DeWolf said some resistance is already present, making selective and targeted treatment critical.

Timing is crucial because worm development and shedding fluctuate with lambing, pasture conditions, farm practices and seasonal reductions in egg production, which can affect FEC accuracy.

Worms have a chance to build resistance with every dewormer application, and under-dosing increases that opportunity, DeWolf said.

“We would much rather err on the side of overdosing slightly than under-dosing,” he said.

“People tend to under-dose slightly, and that’s a way to promote resistance. Making sure you have an accurate idea of what animals are weighing is absolutely essential.”

He said many farms already face low-level resistance, and monitoring FEC of individual animals showing parasite stress, rather than pool testing, helps identify high-burden animals, leading to more effective treatment decisions.

Anita O’Brien, on-farm program lead with Ontario Sheep Farmers, said Taeniaovis, a tapeworm found in farm dogs, guardian dogs or visiting dogs, is not detectable through small ruminant FEC tests. The parasite causes “sheep measles,” which is on the rise and can lead to carcass condemnation.

Dogs contract the parasite by eating raw meat infected with “sheep measles” cysts. They then shed tapeworm eggs onto grass, which sheep ingest while grazing. The parasite moves into the muscle, forming cysts that result in meat being condemned.

“We recommend getting a dog worming program that targets tapeworms,” said O’Brien.

“And any dogs that are coming to the farm, we need to be confident that they are not carrying this tapeworm and leaving it behind.”

The OSF said deadstock must be dealt with promptly to prevent scavenging by dogs or wildlife, which can spread or restart infection cycles.