INNISFAIL, Alta. —Rodney Hollman is a journeyman ironworker by day and a journeyman cattle producer by night.

He and his wife, Tanya, have built up Royal Western Gelbvieh at Innisfail from scratch and are making an impact at sales and shows.

They topped the Gelbvieh auction at last year’s Western Canadian Western Agribition in Regina by selling a $30,000 half interest in a bull named RWG Yikes 1512 to Prairie Hills Gelbvieh in North Dakota.

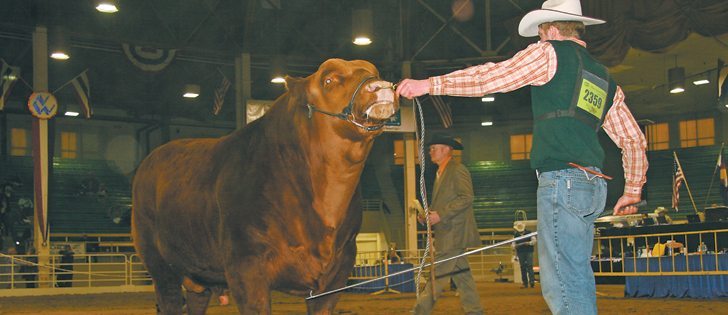

They also had a strong showing at the National Western Stock Show in Denver, making a strong showing with five bulls in the Gelbvieh event held Jan. 14.

Read Also

Quebec pork company calls for transparency around gene-edited pigs

Quebec-based pork company duBreton is calling for transparency around meats from gene-edited pigs on concerns that a lack of mandatory labelling will confuse consumers, and dilute certification claims. The organic sector is also calling for labelling rules.

They won reserve senior champion with a bull named RWG Xtreme Traction 0521 and also entered four bulls in the senior bull calf class, winning first, second, fourth and fifth places.

Agribition was the first time they had entered a consignment sale. All their bulls are normally sold by private treaty to commercial and seed stock producers.

Both work off farm: Rodney is a welder at his family’s business and Tanya is a nurse at the Innisfail hospital. Three children younger than six make trouble-free cattle a must. For the Hollmans, that means Gelbvieh.

Rodney’s father had commercial Gelbvieh-Angus females as recipients for Angus embryos, but he has adopted the breed as a purebred producer.

“A lot of our Gelbvieh cross females were weaning bigger, better calves than a lot of the purebred Angus cattle, so that was a starting point,” he said.

The Gelbvieh breed’s popularity has grown slower than the fast acceptance of Limousin and Simmental since the breeds were imported to Canada 40 years ago. These days, the Hollmans live in a sea of Angus in central Alberta.

“I think we are in the driver’s seat as a breed,” he said. But the big breeds cannot grow forever and market prices will settle, he added.

“I see Charolais and Gelbvieh taking over more market share from those breeds moving forward.

“Gelbvieh as a breed falls very middle of the road as far as commercial acceptance. We do offer a little more lean meat yield and a little more continental flare than an Angus or Hereford bull, but we are not as excessive as a Belgian Blue or a Blond d’ Aquitaine or a really heavy muscled Limousin bull,” he said.

He bought his first purebred female in 1998.

“Back then, it was about winning a few banners and ribbons,” he said.

Hollman decided to become a serious producer in 2004. He and Tanya travelled thousands of kilometres inspecting and selecting from operations across the continent.

“There is no limit to where we will go to find what we are looking for, whether it is North Carolina or Texas or our neighbour. We have herd bulls from a wide variety of places. It is just a matter of finding what you need.”

Some new females are introduced as part of a breeding strategy, but they prefer to retain their own heifers to build their cow families.

“We are willing to sell the bulls almost all the time, but not the females. The genetics our females carry, we use to carry our program forward to the next generation,” he said.

The cows are their factory and selling them is the last resort, even when times get tough.

“Everyone in the world of business builds a factory or a foundation to what makes your livelihood, and you don’t sell it until you are ready to call it quits,” Hollman said.

“That’s what makes my living. I can cash in on her today, but then I give up her next generation of sons and daughters and that is more valuable.”

He originally used artificial insemination, but there wasn’t a wide variety of available Gelbvieh bulls.

“A lot of the better cattle in the North American Gelbvieh herd are not available for sale via an AI tank, so it forces you to go and buy bulls,” he said.

“We got more consistent calf crops.”

Many of their bulls are owned in partnerships.

The Hollman’s calves arrive in June and July while their partners tend to calve earlier, which means the bulls work for a longer season to accommodate everyone’s calving periods.

Bulls work with different sets of females in new environments and the calves can be assessed to see if individual bulls work well in a broader spectrum.

The Hollmans sell their bulls across Canada and the United States.

American interest has increased recently because breeders are looking for diversity. Interest was considerable in breeding an Angus-Gelbvieh hybrid called Balancer, but more producers are looking to return to purebreds, Hollman said.

He said there could be a risk in exporting so many of Canada’s top cattle to the U.S.

“All it would take is two years and at every bull sale the top two young herd sire prospects end up south of the border and you’ve depleted two years worth of breeding seed stock genetics.”

However, Canada still has wide genetic diversity among the 3,000 registered animals. It is not common for one popular bull to be syndicated as often happens in the U.S.

Hollman has worked with Ignenity to use genomic technology to identify carcass profiles and determine whether the cattle are homozygous polled or have a black hide.

It is not the only selection tool the Hollmans use, but it helps determine which are likely to perform poorly and can make sure those bulls do not breed.

Their bull business has turned into a year round enterprise, but they still run the ranch like a commercial outfit.

They stockpile grass for winter grazing that should last until March. This year snow arrived in late October and an ice layer covered it. More snow arrived and young cattle were unable to dig through so the Hollmans were forced to feed them hay.

About 30 bulls are sorted in pens and weighed every month with the expectation they will gain three pounds per day on a pen average.

Feed and grain are tested and Hollman works with two feed representatives for advice.

They did some homework and added barley sprouts from Rahr Malting at Alix, Alta., for the last two years. It is cheaper at $75 a tonne with 24 percent protein. It is a fine granular product dried to three percent moisture. It is then blended to create a balanced ration.

The Hollmans once considered expanding and ranching full time, but they were concerned they would not enjoy the cattle or make strategic breeding plans if the herd was too big. Instead, they decided to model themselves after successful breeders such as Miller Wilson Angus at Bashaw, Alta., where the herd is smaller but the quality control is high with strategic breeding.

“That is a testament that you can accomplish whatever you want to and you don’t need to have 500 or 600 cows,” he said.