Sheep producers say the ban on exports feels like being hit by a train, except they weren’t standing on the track.

A single case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy in an Alberta cow triggered an international export ban on all Canadian ruminants and ruminant products. The ban included sheep and their byproducts.

“There’s not much logical sense in this because sheep don’t get BSE,” said Ian Clark, a Bentley sheep producer and spokesperson for the Alberta Sheep and Wool Commission.

Alberta has Canada’s third largest flock at 140,000 ewes. This latest problem could further reduce breeding numbers and leave many producers in dire financial straits.

Read Also

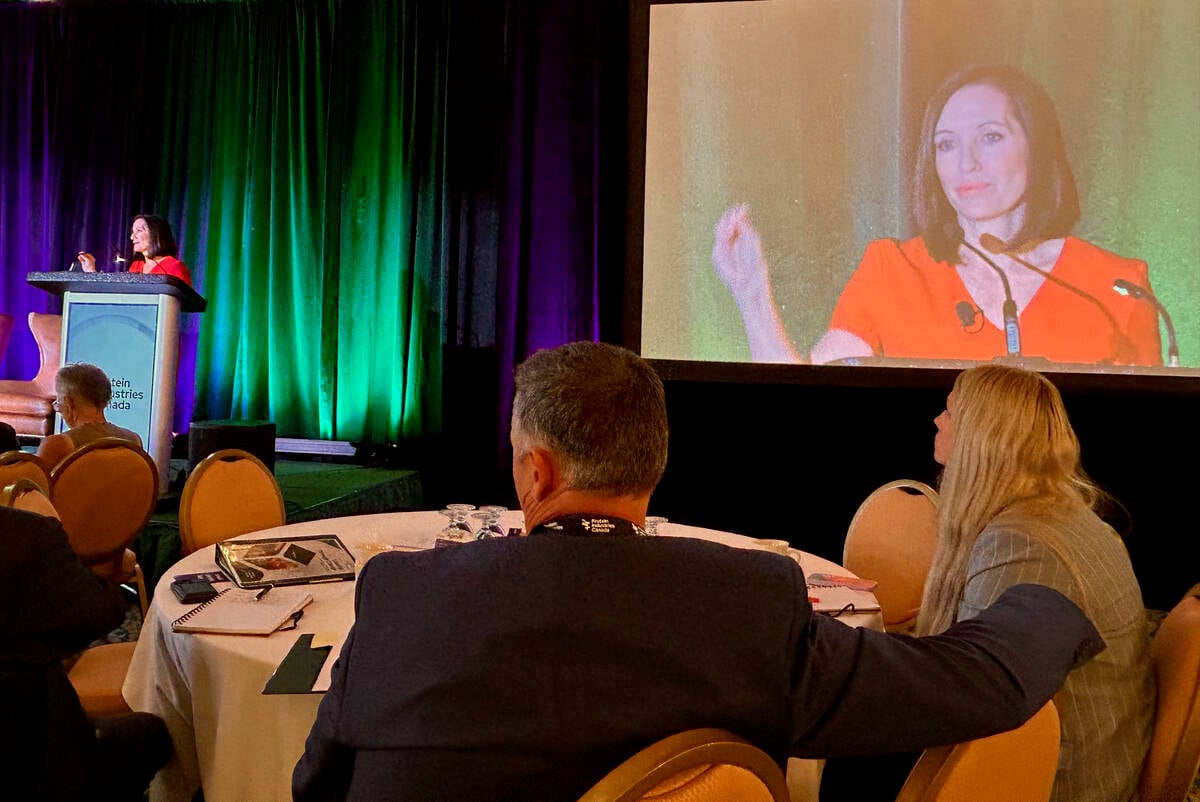

Canada told trade crisis solutions in its hands

Canadians and Canadian exporters need to accept that the old rules of trade are over, and open access to the U.S. market may also be over, says the chief financial correspondent for CTV News.

Last year’s drought forced Alberta to liquidate about 20 percent of its flock. High feed prices have kept many teetering on an economic cliff.

Normal prices for this time of year are around $100-$105 per hundredweight for a market-ready lamb. Since the May 20 BSE announcement, prices have dropped. Central Alberta prices last week were $95 per cwt. and falling.

“If lamb prices had stayed at normal levels, people might have recovered some of their losses,” Clark said.

Most Alberta lamb is marketed between September and December. If sales are restricted to the domestic market this fall, there could be a 25 to 50 percent decline in prices.

The export ban hurts the national market because western born lambs move south and east. Central Canada could be plugged with western and local lamb, which would drive down Atlantic Canada prices that are based primarily on Ontario bids.

“The whole industry is going to have a significant depression in prices,” Clark said.

In addition, feedlots are likely to buy fewer lambs and consequently less grain, spreading the hurt to feed growers. In the last five years Alberta producers embarked on an aggressive export program that saw about half the annual production leave the country.

The losses are personal for Clark.

He raises purebred sheep in central Alberta and has already seen international sales evaporate because of the ban.

About $1 million worth of Alberta sheep genetics were scheduled for sale this year. That could be lost as the border closure continues.

Mexico was the best customer but the United States has prohibited the movement of Canadian stock on its soil.

Overall, Canadian producers export 15 percent of their production worth nearly $20 million annually.

“We have been a healthy industry that allows people to diversify their farm holdings. It’s really a great pity that we can’t continue that kind of positive movement to provide somebody with a way to make some extra dollars on the farm,” said Clark.

Sunterra Meats, a federally inspected lamb processing plant at Innisfail, Alta., fears the worst.

“The longer this goes on, the worse things will get,” said livestock manager Bob Petty.

Meat demand is down and the plant has lost on sales for offal and pelts that were destined for the U.S. and Mexico. Bones, heads and offal must be rendered at an added cost.

A surcharge of $2.50 per lamb and $14.50 per veal calf will be charged at Sunterra to cover rendering costs.

The Canadian Sheep Federation argues sheep should not be included in the ban since they pose no risk to cattle or human health.

The industry has given information to both levels of government to explain the full level of damage so a compensation program can be designed. Funds are available under the BSE compensation package but a payout formula has yet to be calculated.

Confusion over scrapie and BSE is another spectre. During the BSE outbreak in the United Kingdom, it was speculated cattle contracted BSE from feed containing sheep offal infected with scrapie.

Scientific evidence disproved the theory. Feeds contaminated with BSE can pose a risk to sheep, but there is no risk of scrapie being spread to cattle or humans.