Human and pet dog cases of a deadly parasitic disease have recently increased in Western Canada.

In Alberta, the parasite Echinococcus multilocularis has been diagnosed in 17 people between 2013 and 2020. In pet dogs, there were 27 cases in Western Canada between 2009 and 2021 with 18 of those occurring in Alberta. This is likely just the tip of the iceberg of the true number of infections out there.

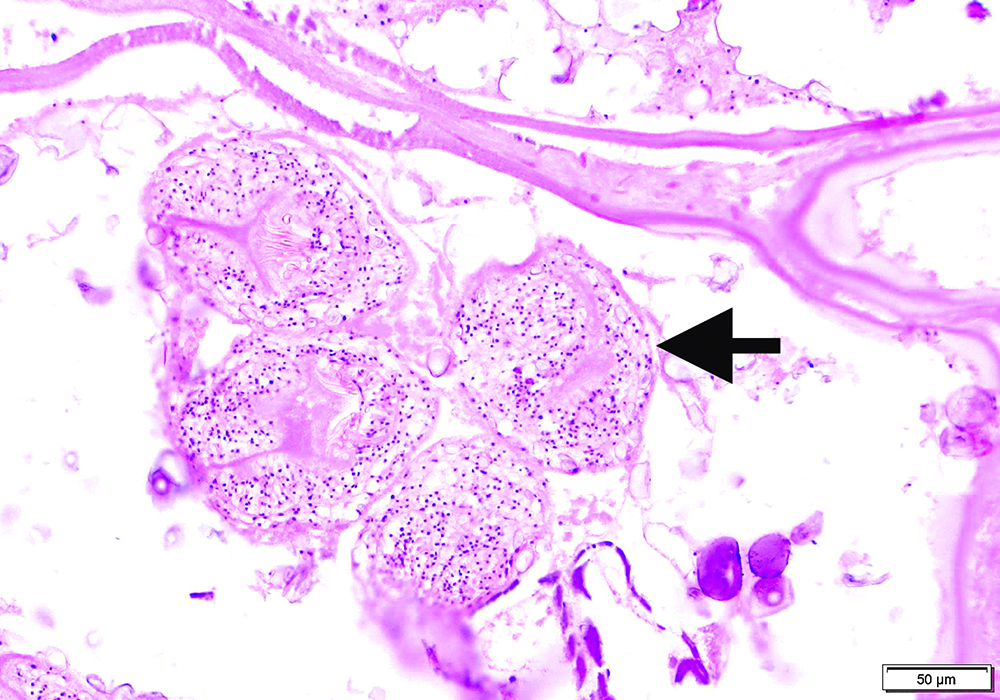

Previous studies have identified coyotes as the major local carrier of this tapeworm and are capable of spreading infective eggs. In natural systems, small rodents consume the eggs and develop the intermediate stage known as alveolar echinococcosis, or AE.

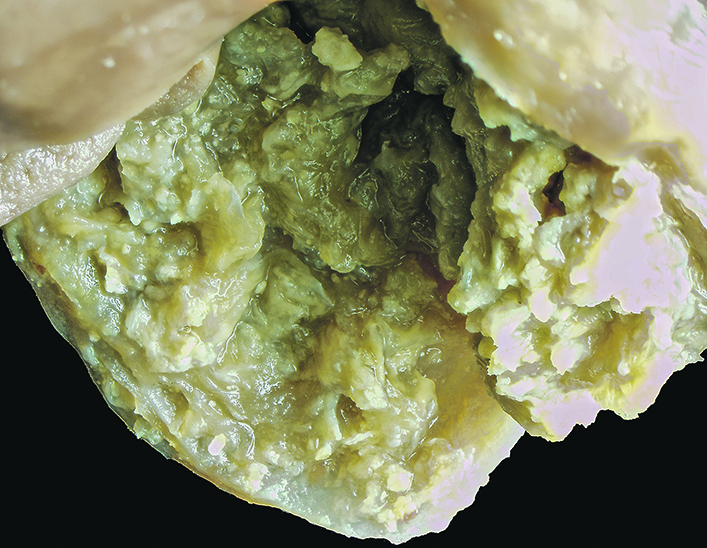

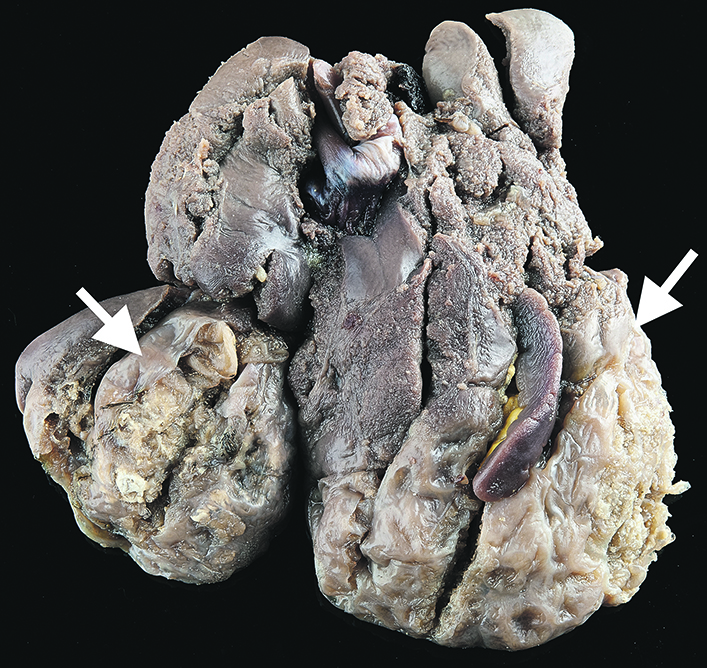

When eaten by hosts like coyotes, the tapeworm develops to its adult form and can produce eggs, thus completing the lifecycle. If people, dogs, or a range of other mammals inadvertently consume the eggs, they can develop the AE form of the disease. It is serious because the parasite develops large liver cysts that can spread internally and eventually kill their host.

Together with my colleagues at the University of Calgary, I have identified that muskrats may be an important but previously overlooked host for this deadly parasite.

In our study, which was recently published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases, we discovered that roughly a quarter of the 93 muskrats we examined were infected with the parasite.

These animals originated from an urban pond system in the City of Calgary. We also identified that nearly 80 percent of these infections were fertile, meaning that if a coyote or other host were to eat the muskrat, they would have a good chance of becoming infected. Previous studies in this area identified voles and mice as parasite hosts, but at a much lower percentage of infection compared to our study.

Our study fills in an important piece of the puzzle about why this parasite is suddenly causing a problem in Western Canada. Muskrats can live in diverse habitats that include ponds, streams and dugouts in rural areas and also within cities.

Our study shows muskrats are very good at hosting this parasite. They may be the key species that perpetuates the parasite lifecycle in cities like Calgary and Edmonton where muskrats and coyotes thrive. With more people and their pet dogs in Western Canada contracting this infection, it is useful to better understand how it is maintained and spread among hosts to reduce the risk of exposure.

Although this study wasn’t about dogs specifically, it is worth discussing how infections in dogs can manifest. Dogs can carry the adult tapeworm in their intestines and spread eggs, which are dangerous to people.

They get this form of the parasite from eating an infected rodent, such as a mouse or muskrat. However, they can also have the intermediate stage that comes from consuming eggs, which would be present in dog or coyote feces. They tend to become quite sick and many dogs with this infection develop large, fluid-filled abdomens. The parasite attacks the liver, creating large, fluid-fill parasite cysts that can spread internally.

Dog owners should take the time to discuss parasite treatment with a veterinarian. There are specific medications to target tapeworm parasites that may not be present in all types of dewormers. I know dogs will be dogs, but as much as possible, it is a good idea to prevent them from consuming animal feces and hunting rodents.

I have several new research directions to follow now that we’ve made this discovery. I’m partnering with other Alberta scientists to examine the muskrat parasite’s DNA. We will compare it to human, dog and coyote cases found in Alberta to see if it is the same strain.

This is important because the current theory for why the parasite is suddenly causing illness is that the European strain was recently introduced. Our future work will determine if the muskrats are indeed carrying the European strain. We also want to know how widespread muskrat infections are across the Prairies.