Babying heifers through their first winter may not improve the cattle herd. Instead, a late gain system can optimize heifers for reproductive success and reduce feed costs by 12 percent, according to one Alberta veterinarian.

Dr. Elizabeth Homerosky says the system helps target first-cycle births and avoids overfeeding animals before they hit grass.

There is no need to wait until heifers reach 65 percent of their mature body weight before putting them with a bull, Homerosky said.

Homerosky suggests producers need only develop heifers to 55 per cent of mature body weight before introducing a bull, and that the practice will typically not hurt the female’s health or increase dystocia rates.

Read Also

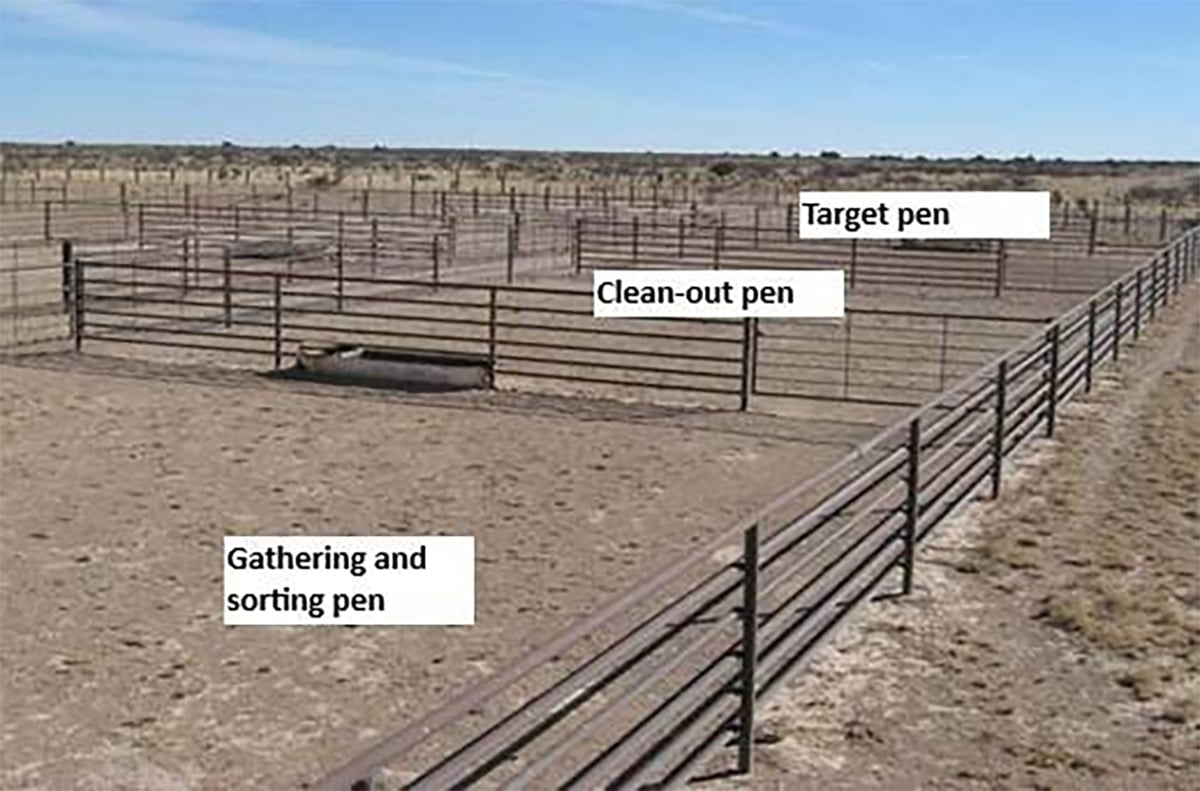

Teamwork and well-designed handling systems part of safely working cattle

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things: the cattle, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

“And it’s very, very economical to do that,” she said.

She compared late gain systems, sometimes referred to as rough-it or extensive systems, to a backgrounding operation “where feed intake is limited until heifers are turned out on grass and you can take advantage of compensatory gain to achieve your desired per cent of mature body weight.”

Low but efficient gains are the target in this system.

“Basically, what we’re doing is we’re treating her more like a cow. And the more you treat her like a cow, the better cow she’s going to be,” said Homerosky.

In one study at the University of Nebraska, researchers compared the reproductive results of heifers managed under two weight-gain systems: even and late gain. Both groups were then exposed to a bull for two cycles over 42 days.

At first, there seemed to be little difference. Conception rates in both groups hovered around 85 percent. The advantage emerged once time of conception was added to the equation.

The late gain group saw 15 percent more pregnancies in the first cycle, resulting in “better momentum” and “a more front-end-loaded calving season,” Homerosky said.

The late gain group also consumed about 12 percent less feed.

“If I could virtually give everyone a coupon tonight for 12 percent off your winter feeding costs, that’s something we would all jump at,” said Homerosky.

First-cycle pregnancies also tend to pay off in the sale ring. Early conception means earlier calving and more time for that calf to grow before weaning.

Homerosky pointed to research from the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center, which tracked 16,000 heifer pregnancies over 21 years and found that first-cycle conceptions came with a noted increase in weaning weight. The study also found that advantage followed into future pregnancies, up to the animal’s sixth calf.

“When you add up the additional weaning weight, it’s almost as if these first-cycle calving heifers give you the equivalent of … another calf,” she said.

For best results, Homerosky recommended limiting the breeding season to two cycles within 30 days (42 maximum). This could be challenging for many farms, but the tight window allows producers to select for the best breeding stock, she said.

“If you’re going through with this, you really need to shorten up your breeding season. If you expose those girls for three cycles, you’re undoing all your hard work because you’re allowing them too many chances.”

Newcomers to the strategy may also want to keep back more heifers.

“When we first tried extensively developing our heifers eight or nine years ago, we discovered that our heifers weren’t as fertile as we thought they were and only achieved 70 percent pregnancy rate following two cycles,” Homerosky said.

“After selecting for improved efficiency, we are now in that 85-plus percent range.”

She also stressed that the system works best with spring calving in April, May and June.

“If you’re trying to calve in January, February or March, you’re probably just not aligned with Mother Nature enough to where you can take advantage of the flushing effect.”

Stephen Hughes, a rancher from Longview, Alta., who uses a similar system, said a 30-day breeding window is a good tool for selecting seed stock, rather than subsidizing heifers that likely won’t make it as breeding animals.

“I’m sorting from the bottom,” said Hughes. “You can’t identify the best cattle by phenotype strictly. You can cut some out for poor phenotype, but (with) that 30 days, you’re cutting out the cattle that can’t cut it in your management … situation.”