INNISFAIL, Alta. – After an upward ride on the red meat sales graph, lamb prices are poised for a slide.

The last year and a half set record prices that went as high as $160 for a market lamb.

In June prices slipped below $1.20 a pound and the latest sales range is $1.09-$1.24, said Doug Laurie, of North Central Sheep and Goat Sales. The organization runs sales out of the Edmonton Stockyards every month.

The decrease is attributed partly to seasonal fluctuations when more lambs come on stream.

Read Also

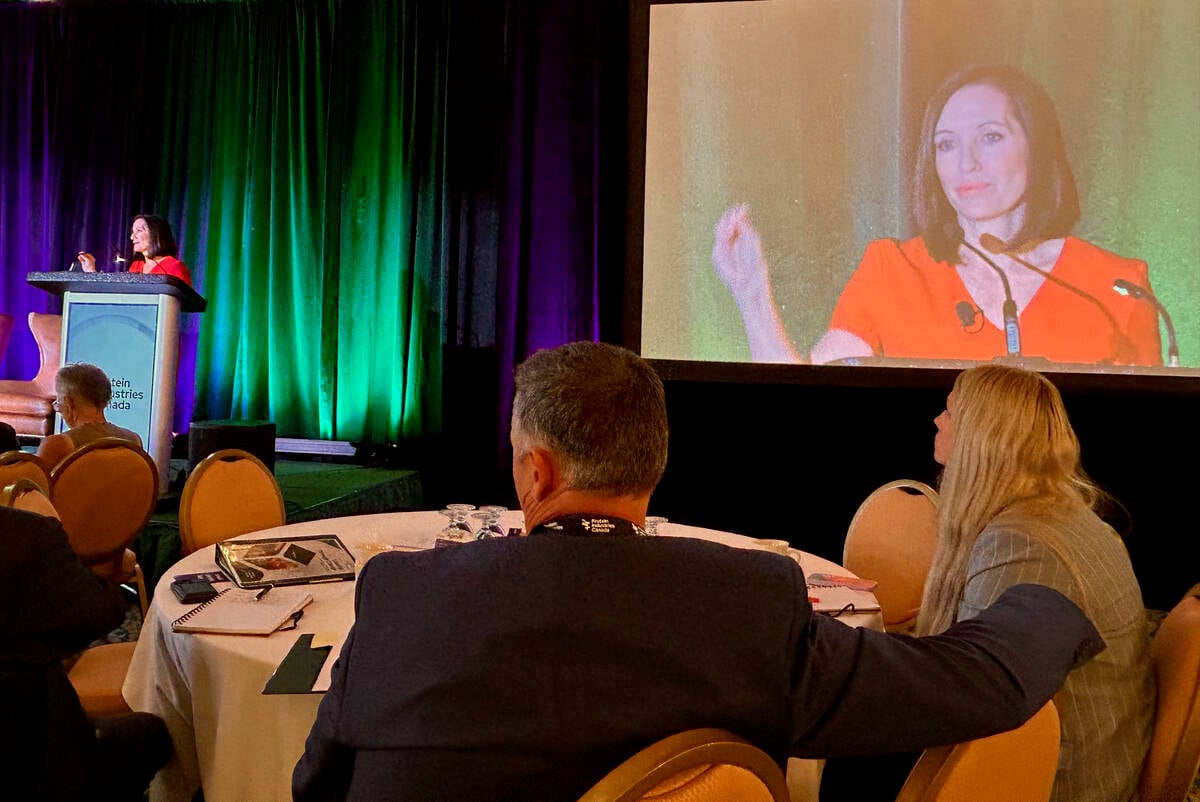

Canada told trade crisis solutions in its hands

Canadians and Canadian exporters need to accept that the old rules of trade are over, and open access to the U.S. market may also be over, says the chief financial correspondent for CTV News.

“It’s normal at this time of year for the prices to slide a little because of volume coming into the marketplace,” said Laurie. “It will pick up again this fall and hold through the winter.”

Prices also fell in the United States when some feedlots overfed lambs up to 180 pounds.

“It resulted in a lot more product on the market and a lot more fat which is very difficult to dispose of in the market. It compounds itself because lamb is such a fragile market,” said Will Verboven, manager of the Alberta Sheep and Wool Commission.

Nevertheless, the commodity organization is urging people to expand their flocks.

After years of prices in the dumps, producers may be reluctant to grow more lamb even when slaughter plants like Canada West Foods in Innisfail need continuous supplies. They have to tell customers that at certain times of the year they have no fresh lamb available, said Gordon Fulton, chair of the Alberta Sheep and Wool Commission.

Verboven said there is a mistaken idea that tight lamb supplies are good for producers.

“There is this rationale by keeping the numbers low, it keeps prices up,” Verboven said.

However, the price of lamb is set by the Americans and they will displace local fresh product if Canadian lamb is in short supply.

“From mid April to all May there are virtually no lambs,” said Roy Genge, manager of the specialty meats trade at Canada West Foods during a producer education day at the plant.

“We need the flock expansion because we need them year round,” he said.

Laurie said the industry could grow by 15 percent in lamb volume but massive expansion could hurt prices. Expansion is slow, however, because people are selling ewe lambs for meat rather than holding them back as breeding stock.

Phil Huber, a Wyoming lamb feeder with 30,000 head capacity, said the market in the U.S. has deteriorated. As head of the American lamb feeders association, he blames greed and failure to calculate expenses.

People should have figured out their cost of gain more closely. Don’t look at break even, look at profits, he said.

“Breaking even is like kissing your sister,” he said. “If 40 percent of the feeders had done this, we wouldn’t be in the disaster we’re in right now in the United States.”

They thought good prices per pound translated into more money if there was more weight.

Some feeders held lambs until they weighed 180 lb. and ended up losing $70 (U.S.) a head.

Lambs went into the feedlot at $1.08 and came out at 180 lb. worth 58 cents a lb., said Huber.

Shoulders were so big, the processors couldn’t package them properly. Some of these oversized carcasses ended up in Mexico for 60 cents per lb.

“That has got to teach us something for another 10 years,” he said.

Besides cost of gain, the sheep producer has to consider good stockmanship where lambs are sorted according to weight and selected for quality.

“A producer has to improve the gainability of the lamb, the conformation of the lamb and they need a healthy lamb,” Huber said.

“As for exotic breeds, let the research stations and colleges fool with them for awhile,” he said.

Producers in Canada and the U.S. need to look more closely at contracting their lambs to guarantee price and supply because the packers and the producers have to make money for both to survive.