Bob Jackson doesn’t worry much about inbreeding within his herd of

bison in southern Iowa because he firmly believes that animals have

good instincts.

“You don’t ever have to worry about inbreeding because it’s exactly

the same as you and I, where the girl always looks more exciting in the

school that is your neighbouring school,” said Jackson.

Allowing bison to live instinctively is a key philosophy on Jackson’s ranch, because he raises the animals in family groups.

Read Also

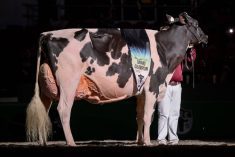

Canadian-bred cow wins World Dairy Expo Holstein show

A cow bred in Saskatchewan, Lovhill Sidekick Kandy Cane, is the Grand Champion Holstein at the 2025 World Dairy Expo.

“They’re in about five different family units,” said Jackson, who

believes he’s the only rancher in the world raising bison in this

fashion.

Jackson and his wife Susan raise 400 bison on 1,000 acres of native

grassland pasture near Promise City, Iowa, about 150 kilometres south

of Des Moines.

At their ranch, known as Tall Grass Bison, the animals are raised

in family groups to enhance animal welfare and improve the quality of

the meat, according to a promotional brochure.

When calves are separated from cows and relatives at an early age,

it can cause chronic stress that affects the quality of the meat,

Jackson explained.

“That means you have stress inherent in every one of those animals

that don’t have the dependency, the support systems, of the extended

family.

“If you have animals that don’t have all that stress… then that meat is a lot more tender and a lot more flavourful.”

In addition, when Jackson slaughters bison, he doesn’t pick out

animals of a certain age group. An entire family group is slaughtered.

“We field slaughtered one large family unit (140 animals) this last spring, “ he noted.

“That means you shoot everything from calves up to 20-25 year old bulls and cows.”

Slaughter essential

All the animals in the family group are slaughtered because

otherwise the remaining family groups on the ranch would ostracize the

animals.

Jackson came up with the idea of raising bison in family groups

while working as a backcountry ranger in Yellowstone National Park back

in the 1970s.

“I was stationed at the furthest point from a road in the lower 48

states. It’s 32 miles off of a road and it was a two-day horse ride to

get in there,” he said, adding that level of remoteness is nothing

compared to the Canadian wilderness.

Jackson, who served as a ranger for 30 years, spent hundreds of

hours observing the park’s bison herd and spent many nights reading

historical accounts of bison hunts.

The experience and knowledge inspired him to start raising bison at his parent’s farm in northern Iowa in the late 1970s.

Later, he expanded his herd at his current ranch, south of Des Moines.

The family groups on the Tall Grass Bison ranch share the same

pasture but they don’t fight for territory if enough resources are

available, Jackson said. In the winter, 1,000 acres cannot sustain all

of the herds, so Jackson feeds grass hay.

“We’ll feed them in the winter at different locations in the pasture so that family can eat together, so to speak.”

Bison herds are similar to the matriarchal herds of elephants, Jackson said, with an extended family and distinct roles.

“You have to have the grandmothers, have to have the mothers, have

to have the protective grandfather, you have to have the breeding

male,” he said.

The maximum number in a family group is 300, Jackson said, because that represents the limit to familial recognition.

A typical family group may have 50 to 70 in the main group, with

several satellite groups that depend upon the primary group for

support.

Asked about the potential of inbreeding within a family, Jackson

repeated his comment that bison instinctively breed with a member of a

different family group.

“Sort of like humans, you try to pick traits that are different than

you. Instinctively the (bison) know that… You get line breeding without

inbreeding.”

Raising bison as bison, rather than raising bison as cattle, is an

idea that’s catching on in the United States, said Fred Provenza, a

professor emeritus in the department of Wildland Re-sources at Utah

State University.

“Let’s try to figure out how we can still get production out of

them, but with them being more like a bison,” said Provenza, who

specializes in animal behaviour and management.

“We’ve all ended up talking about how would bison be behaving under

natural conditions? And (there’s) this idea of they’d very likely be in

extended families.”

Creating a herd with distinct family groups is not done overnight,

said Jackson, who has been developing his herd for more than 30 years.

Building family groups, with grandmothers, grandfathers and other distinct roles, takes 12 to 15 years.

Once established, bison ranchers can tap into the demand for

naturally raised beef, said Jackson, who sells his bison meat online.

Another benefit is that older animals can be sold based on a clean,

fresh taste and the additional nutrients in their meat, Jackson said.