For years, rural people have lamented that there are not enough opportunities to keep people in the country.

Now, with an anticipated expansion of western Canadian agriculture, the lament from farm managers is that they cannot find enough skilled labor to fill the spots.

A strong back and a weak mind no longer are sufficient qualifications. Modern-day farm workers are expected to have skills to operate sophisticated harvesting equipment, manage precise animal-feeding schedules and understand complex chemical application instructions.

The race is on to train and attract skilled agricultural workers. Some farm managers are doing some soul-searching about wages and conditions they offer.

Read Also

Canadian-bred cow wins World Dairy Expo Holstein show

A cow bred in Saskatchewan, Lovhill Sidekick Kandy Cane, is the Grand Champion Holstein at the 2025 World Dairy Expo.

Others are giving up in despair over what they see as a lack of affordable skilled help.

In this special report, Calgary-based Western Producer correspondent Barbara Duckworth explores the exploding issue of the demand for farm labor.

In W.O. Mitchell’s classic prairie tale Jake and the Kid, the hired man is part of the farm family, sharing meals and his own brand of wisdom about love, life and how to pick rocks without ever lifting a stone himself.

These days, farm employers are not looking for an exceptional hired man like Jake.

They would be content with skilled people to work in the expanding livestock business, horticulture and farm service companies.

It is not easy.

City lights lure young people away every year with promises of better jobs. Agriculture isn’t sexy enough to attract young people.

A generation ago, young people could be relied on to pitch-in during busy times like harvest or calving. But many of today’s youth find off-farm jobs that pay the same or better for less effort.

“My kids won’t go anywhere near a farm. We’re victims of our own affluence in many ways,” laments Steve Torrance of the British Columbia Horticulture Council. “Our young people won’t work on farms for the summertime. We’re having to do more with less and less people.”

It is the same story elsewhere.

In Manitoba’s expanding hog industry, there is great demand for barn staff.

Smaller outfits often hire and train someone, only to have them lured away by a larger corporate farm that can afford

better wages and benefits, said rural development specialist Richard Rounds of Brandon University.

In Alberta, a healthy economy entices young people to construction jobs or the oil patch where the work is hard but the money is good.

“In a rather tight labor market, the farm occupation scene isn’t that competitive with other choices,” said Doug Taylor, who manages the Green Certificate program for Alberta Agriculture. Green Certificate is an apprenticeship-style training program for farm workers.

“The nub of the issue is that a business needs staff and if it can’t compete on the wage market for the people, where does that lead us?”

The labor shortage is felt by corporations as well as farmers.

Agricore employs about 2,000 people across the West.

Lately, the grain company has hired more people with agronomy degrees and the competition for graduates is fierce, said chief executive officer Gord Cummings. “Five or six years ago we didn’t need this type of person.”

Agri-business now needs people to work with new farm chemicals or deal with emerging weed and insect problems.

Farmers expect the company to employ people with the answers, said Cummings.

Like many companies, Agricore has started hiring summer students and offers scholarships to those who promise to

return to the company.

These kinds of incentives are not

uncommon.

The University of Saskatchewan placement service for agriculture students organizes many summer positions every year, ranging from sales to research in the corporate sector.

For many, this is a foot in the door leading to a job after graduation, said placement officer Brent Wellman.

The same scenario happens at Alberta’s Olds College.

The job outlook for graduates in all their industry-driven courses is positive, said career employment adviser Susan Roper. “There are more employers than students.”

Most postings are for sales agronomy jobs. Companies want students who have a broad knowledge of fertilizers, crops, some business acumen and good communications skills with farmers.

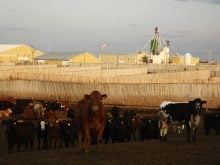

There also is plenty of work for the hands in feedlots, swine, meat processing and horticulture.

Recruiting is busiest in January and February although this past year, some companies came looking in the fall, said Roper.

Private farm employment agencies also are busy.

Patricia Black runs a private employment agency in Lethbridge, Alta. ResumŽs come in every day. “For every good resumŽ I get, I wish I could clone that person.”

ResumŽs flow in from as far away as

Atlantic Canada.

She takes job orders for Alberta and some B.C. employers. They all want experienced people to work as feedlot pen checkers, hog barn workers and farm managers.

The best farm managers retain staff for two to five years. Others see staff come and go through a virtual revolving door.

Some farmers still want hired hands who can turn their efforts to anything. Most want people who can operate high-tech equip-ment and adapt to new ways of working.

“Every farmer wants a 20-year-old guy with 40 years of experience,” said job agency operator Ron Hiebert of Red Deer, Alta.

Few employers provide training for inexperienced people because of the cost involved, said Hiebert.

British Columbian farm work may be different, but the labor supply is just as tight, said Marlene Derkson of the B.C. Agriculture Labor Pool.

“If there’s a good position being offered, I have no trouble getting people,” she said.

Her office has up to 4,500 names in a cross-Canada employee data base. Qualifications range from general laborer to PhDs.

The greatest demand is in the booming horticultural trades, especially in vegetable and flower greenhouses where employers may need 12 to 100 people.

Horticulture has peak planting and harvesting times when seasonal workers are needed. They can be the hardest jobs to fill.

More highly skilled people with degrees or equivalent experience are needed for year-round jobs, which might include pruning, plant propagation or experience in integrated pest management.

B.C. is one of the few provinces with regulations governing farm workers. They get a minimum wage of $7.15 per hour.

Some employers offer better packages, including dental benefits.

B.C. employers also must pay worker’s compensation premiums.