If Lois Andrew didn’t know better, she would think this was October rather than July.

“We have not had an inch of rain since June. If you look across the prairie, it’s straw,” she said.

She and her husband Tim ranch near Youngstown in southeastern Alberta.

The situation is the same across the southern third and east-central regions of the province. Pastures never greened up and a walk across a hay field produces a crunching sound.

Andrew said this year’s silage crop is only 30 centimetres high and hay fields produced half a bale per acre. The only thing that might save them is forage carryover from last year when rainfall was more plentiful.

Read Also

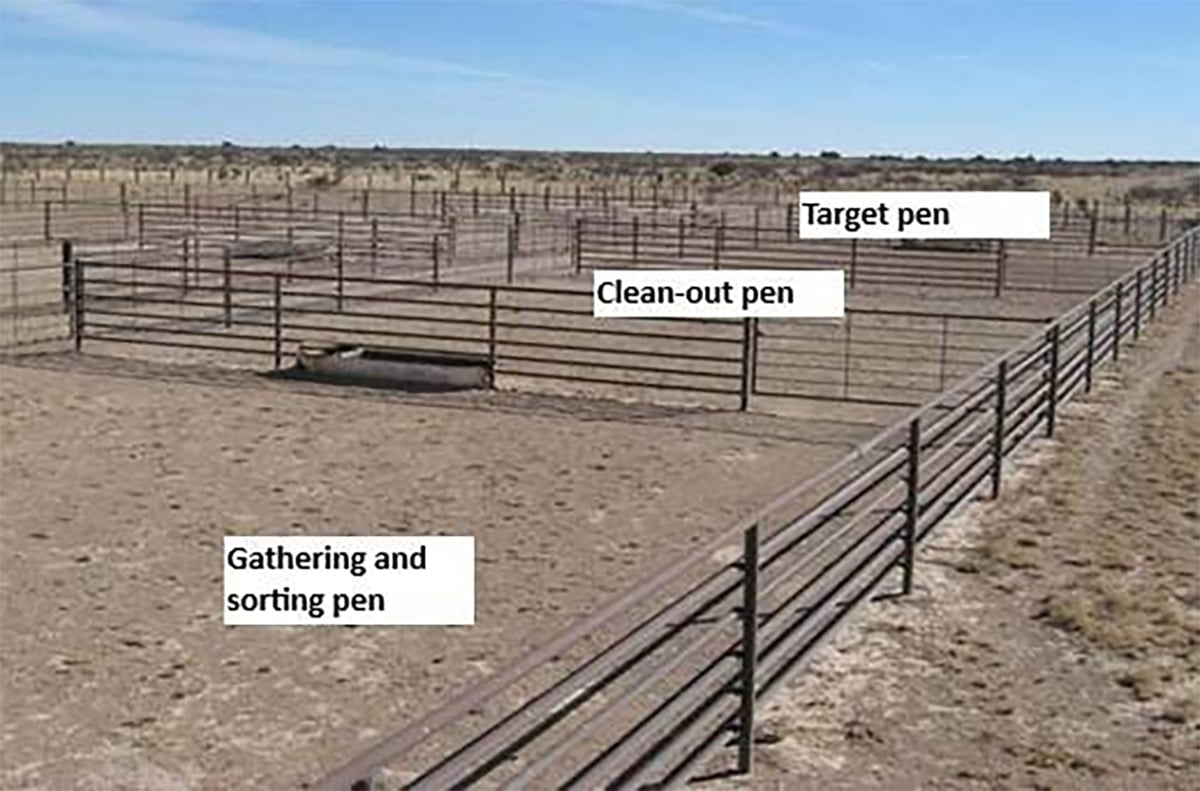

Teamwork and well-designed handling systems part of safely working cattle

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things: the cattle, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

In addition to a short hay crop and burned pastures, the dugouts are running low.

The Andrews set out solar panels to drive pumps and preserve water quality. But the situation looks desperate in terms of quantity.

“We may be trailing the cattle home early,” she said.

The situation is similar for Keith Everts in southwestern Alberta near Pincher Creek.

“Even the gophers are packing a lunch,” he said. “Everything is yellow except for the cereals. I can’t figure out how they are holding on.”

People will likely cut the grains for greenfeed because the kernels are not filling. Everts’ hay yield is about a tenth of a tonne per acre.

“I wonder why I’m bothering but every bale adds up when it’s worth $120 a tonne,” he said. “Everybody will be buying feed this year.”

Northeast at Thorhild, Gene Pedersen is looking for 300 yearlings to custom graze his lush pastures. Ample rainfall this spring has brought the bloom back to an area that suffered severe drought for several years.

“This spring we were desperately dry and then we started to get rain. I’ll never complain again,” he said.

But prolonged drought has dried dugouts and with no runoff this spring, water shortages are looming.

“We need four feet of snow this winter to fill my dugouts,” Pedersen said. Pumping may be an option if he gets permission to draw water from a creek trickling across his land.

In the sales ring, some cattle have started moving early either to feedlots or to greener pastures outside the region.

“We’re not talking great big numbers yet, but it is fairly disastrous down here,” said Brant Hurlburt of Fort Macleod Auction.

He doesn’t expect exorbitant feed prices because it is still early in the season.

While dryland hay is almost non-existent in southern regions, some crops could be baled as greenfeed and that might bring the price of feed down. He also expects feed barley prices to be moderate this fall to control the price of roughage.

That does not diminish the serious position some producers are facing.

“There’s a lot of places where it never grew anything at all since last year. They were feeding cows last winter and they’re still feeding cows.”

Myron Bjorge, provincial forage specialist, said this year’s rainfall for the stricken regions is about 40 percent of average.

“Water becomes as much as a problem as pasture,” he said.

A good rain now would bring back a second cut of alfalfa and revitalize cereals, brome grass and fescue.