RENO, Nev. – Producers who want to capture as much value as possible from their cull cows and bulls shouldn’t wait too long.

That is one of the recommendations from a U.S. cow and bull beef quality audit conducted in 23 packing plants in 11 states. It is the third audit since 1994.

“You have to make culling decisions early,” said Dan Hale, one of the meat scientists from seven U.S. universities involved in the audit.

Timely culling of mature animals before they are too old or thin can provide a better return. Thin cows use muscle tissue to stay alive and consequently the dressing percentage is low. Selling the animals sooner also prevents them from becoming sick and possibly being condemned, he told a seminar at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association annual convention held in Reno last month.

Read Also

Pork sector targets sustainability

Manitoba Pork has a new guiding document, entitled Building a Sustainable Future, outlining its sustainability goals for the years to come.

“As we look at shrinking profits, we need to get every dollar out of everything we sell,” said Ron Gill, an auditor from Texas A & M University.

The two scientists advised producers to condition score these animals three months before calving to help make marketing decisions. If the cows are thin, they can be fed more to make them more salable.

Hale said depending on the region and the breed, an eight-year-old cow is probably reaching the end of its productive life with less milk production and lower fertility. Many do well until they are 12 but keeping a cow one more year is often a bad idea, he added.

“People don’t turn their cows over fast enough.”

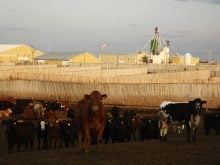

Cow meat is a large part of the beef mix, appearing as ground beef, cheap steaks, filets wrapped in bacon and processed meat. The U.S. national school lunch program, which feeds 30 million children a day, is a major user of cow meat.

“You would be amazed where you find the beef from these cull cows and bulls,” Gill said.

Six million mature animals were processed in the United States last year, a seven percent increase in cow slaughter from 2005.

The main reasons for culling are age, infertility and farm economics. It is estimated 16 percent of farm income is derived from selling cows and bulls each year.

U.S. plants don’t grade cows, but most have their own quality assessment system, and the auditors noted many consistencies.

Canner cows (thin animals) dress out at 40 to 46 percent, which is the percentage of the live animal that ends up as a carcass. A cow in good condition dresses out at 55 to 60 percent.

About 60 percent of the cows in the audit ended up in the mid-range for body condition, 10 percent are very thin and 10 percent are too fat. Average carcass weight was 670 pounds.

This audit found more thin cows than the one in 1999, probably because more producers in drought regions are sending cows to market when they run out of feed.

Visible defects were down.

Cancer eye is not as prevalent as it once was. It is a disease that does not get better so animals should be culled before the carcass is condemned.

In 2004, Congress passed a law prohibiting the sale and movement of downers. Almost none of these showed up in the audit, indicating producers have complied by shipping animals before they are sick and in distress.

Knots from injections were down; 95.5 percent had no visible knots in the neck.

Chute design is part of the problem because it is hard to get at the animal to inject it in the right place. Also, some producers do not know how to do it properly so injection site injuries can still happen.

While neck injuries were down, more beef cows suffered hip injuries. About 15 percent had lesions in the bottom and top rounds in the hip area appearing as a woody callous, open lesion or fibrous scar tissue. These injuries are an even greater problem in dairy cows.

Lameness was noted more often in beef cows than dairy animals.

The audit committee is recommending more training in low stress handling and transportation so animals arrive in good shape with fewer bruises and other injuries. It is also advising producers to consider the distance that culls must travel to slaughter. The average distance is 760 kilometres but many travel more than 1,600 km.

“We need to make sure the people working for us are doing what they are supposed to do. It is a real problem in our industry,” Gill said.

Producers also need to realize that what they think of as normal animal husbandry could be considered abuse to others.

Handlers should not have electrical prods or whips in their hands because if they carry them, they will use them. The audit found one-third of the plants used electrical prods but also found that plant staff used nonaggressive methods to move animals 86 percent of the time.

This audit detected more antibiotic residues, but that may be partly because more sampling is taking place at plants.

Traceability trials showed the auditors were able to trace 71 percent of the cattle back to farm. Some owners could not be found, which was blamed on incorrect records or people removing identification.