PHOENIX, Ariz. – American cattle producers may have animals spreading bovine viral diarrhea through their herds without realizing it.

Researchers believe seven percent of animals with BVD persistently infected while the rest are suffering acute infection at a cost of $56 million US per year in the United States.

“There is the perception that it is involved in a fair number of wrecks, University of Missouri veterinarian Bob Larsen said Jan. 28 during a BVD discussion at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association convention in Phoenix.

“It is maybe 10-20 percent, which is very significant.”

Read Also

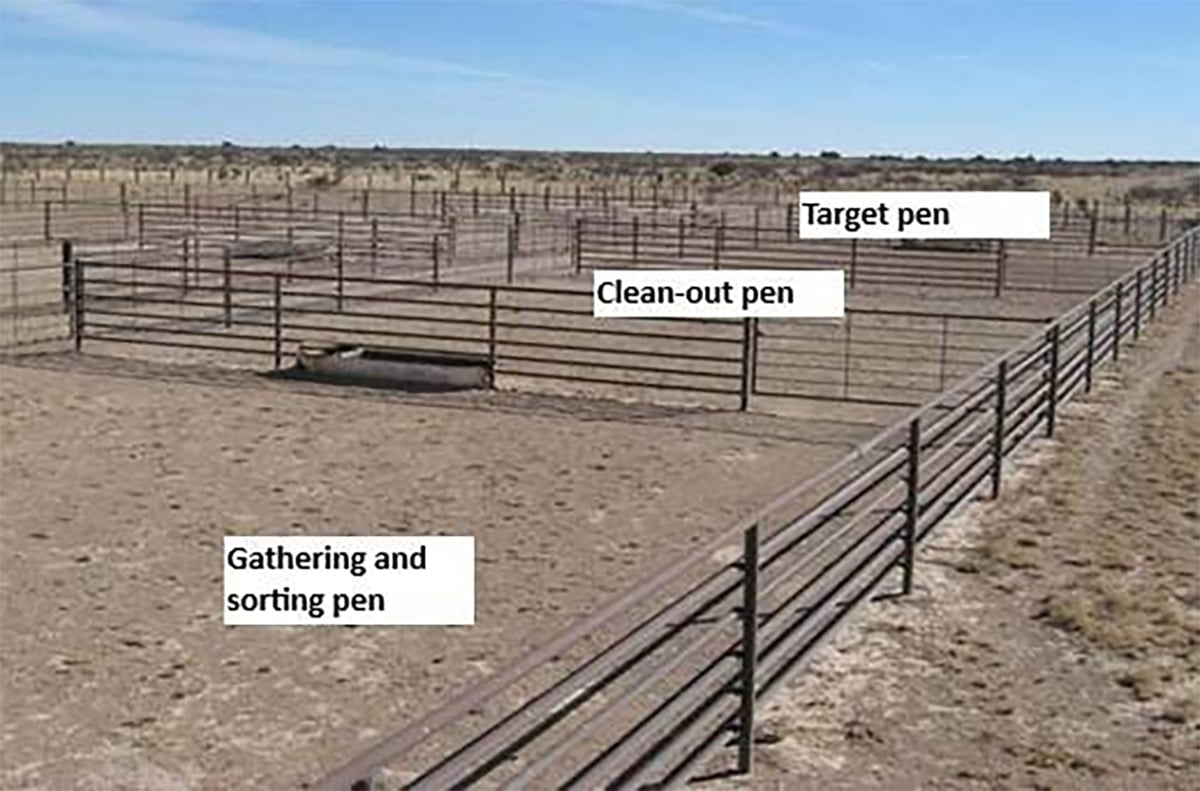

Teamwork and well-designed handling systems part of safely working cattle

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things: the cattle, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

The NCBA has proposed a North American strategy to control and monitor the disease. Researchers say national identification could help track the path of BVD.

It is a frustrating condition because it can resemble other problems such as genetic defects. Infected animals fail to thrive, may develop barrel-shaped bodies and have difficulty developing long bones and muscle.

Congenital defects include sickle hocks, deer face, short stature, easily broken bones, poor coat or stress tendency. If the cerebellum is affected, the animal appears wobbly.

Cows may experience delayed breeding, while fetal infection may lead to abortion, absorption of the fetus or mummification.

BVD could be part of a scours outbreak or an increased number of pinkeye or pneumonia cases among calves.

Julia Ridpath, a researcher with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said BVD makes everything else look worse.

“BVD attacks the immune system. The very defence system the animal is trying to use is the area the virus goes after.”

Types 1 and 2 are the main strains and animals respond differently to each. All types can lead to an array of infections while in other instances, the disease goes undetected. In fact, 42 percent of samples submitted to diagnostic labs were not originally suspected as BVD.

Persistently infected cattle are the primary culprits in spreading the disease, shedding the virus in body secretions throughout their lives. A high percentage die early but some can survive and end up in feedlots, infecting pen mates.

Transmission may be direct contact from animal to animal or by inhaling or ingesting the virus. Air transport is possible over short distances and animals can become infected within an hour.

If a pregnant cow becomes infected, its fetus is likely to be infected as well.

“This is the type of infection that can result in a persistently infected animal. They are little virus factories,” Larson said.

First trimester exposure can result in abortion, fetal absorption or a persistently infected calf that is likely to die early.

The fetus may survive second trimester exposure but it could be born persistently infected or have birth defects.

Third trimester exposure may produce calves that appear normal at birth but develop trouble later.

Ridpath said surveillance takes a number of routes.

Producers should look for patterns where there are unexplained losses in the herd. The disease frequently enters through newly purchased bred heifers carrying infected fetuses.

Control must be thorough and involves tests, vaccine programs and monitoring of overall herd health.

Tests involve taking a small notch of skin from the ear.

The samples are stained and when viewed under the microscope, virus reservoirs that look like brown dots appear. It is important to ask laboratories for tests covering Type 1 and 2 strains.

All cows pregnant at the time of testing must be removed from the breeding herd because they could be carrying a fetus with unknown status. The fetus cannot be tested.

Necropsies should be conducted on dead calves. A typical BVD-infected calf has an ulcerated esophagus and erosions in the mouth.

Researcher Dan Grooms of Michigan State University said numerous vaccines are available.

Killed vaccines are safer because the virus is dead and cannot replicate and pass through the placenta to harm a fetus. They are more stable, but the protection is less effective than modified live vaccines, which provide better and longer protection but don’t guarantee 100 percent immunity.

The immune response is more realistic compared to a killed vaccine, but if handled incorrectly, the vaccine could die. It has a low potential to cause disease.

Grooms said cows should be vaccinated before pregnancy, but acknowledged that can be difficult. Some modified live vaccines are available for pregnant cows but it’s not the best way to go.

“Most of the problems occur early on in gestation so we would like to maximize protection early.”

He also suggested vaccinating feedlot cattle because they could be easily exposed to BVD while travelling to the yard or within pens.

He advised producers to be good consumers and check vaccine labels. Some contain different ingredients and provide different levels of control.

Grooms recommends two doses of Type 1 and 2 vaccines, with a modified live vaccine 30 days before breeding heifers. Cows should receive one dose of either type.

Fed cattle should receive two doses, with at least one being a modified live vaccine.

As well, kill the persistently infected calves and segregate their mothers. The dam does not have to be culled because it is likely immune.

Thin and sick animals should be tested.

New animals entering the herd should be tested as a precaution.

Bulls are not usually infected but should be tested if cows fail to get pregnant. The disease could also pass through semen.

Test open cows, especially if the calf died.

Farms using embryo transfers should ensure the recipients are BVD free. The host cow could infect expensive embryos.

Try and get replacements from certified disease-free herds. A low-risk herd is probably all right, especially if it is a repeat client and management is known.

Watch animal movement. Even a 4-H show calf coming in contact with sick animals from other farms could still infect a closed herd.

Another good control measure is to manage fence lines whenever possible. Avoid putting pregnant cows next to stocker cattle or near a neighbour whose cattle have BVD.