Consecutive years of drought and problems brought on by the discovery of BSE are forcing an Alberta ranching couple to retire, bringing an end to 40 years of trying to build a better beef animal.

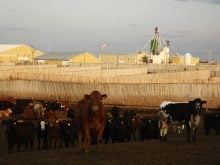

Chuck and Jean Raines named their breed the Mountaineer Breton Spots, creating an animal that is two-thirds Angus with a mix of Shorthorn and Holstein. Meticulous breeding and performance records have been maintained on every animal with the ultimate goal being high quality beef.

But several years of drought, volatile markets due to BSE and Chuck Raines’s poor health have made maintaining the closed herd more than the couple could manage.

Read Also

Pork sector targets sustainability

Manitoba Pork has a new guiding document, entitled Building a Sustainable Future, outlining its sustainability goals for the years to come.

“We would like to see someone take it over,” he said.

Raines estimated he invested $500,000 in research and development of this specialty breed.

And at first, it took time for buyers to accept the multi-coloured steer calves as high performance beef animals.

“At first in the auction market, they put them through as Longhorns,” said Jean.

“It wasn’t until the buyers got to know them as Chuck Raines’s Mountaineer cattle, they did better,” Jean said.

Ranch records show a slightly better than average carcass size with the same level of inputs used on an average performing herd.

“These cattle will out perform the best of Angus and they are consistent at all levels of performance, calving, weaning, yearling and carcass,” Chuck said.

In 2001, each cow turned a profit of $400 but by 2005 the books show a loss of $300 per animal. Farm income has been slashed and eroded the equity built up since the couple started farming south of Airdrie 50 years ago.

“We got $28,000 in government assistance last year and we paid over half of it in tax,” he said.

Raines wants someone to take over the herd and continue developing it into a recognized breed, as well as maintaining the records necessary.

“You’ve got to keep detailed records to know what you’ve done not only if you are right, but in case something goes wrong,” he said.

His records showed him where line breeding was successful or where improvements were needed to develop the kind of cattle that fit his criteria and management philosophy.

“We started with seven basic rules,” he said. Those included insisting all cows wean a calf every year and producing bulls that work on heifers to produce calves around 80 pounds to reduce birthing problems.

“You don’t have to have a high birth weight to get a high gaining, economical steer,” he said.

The Raines immunize calves before weaning to prevent illness in the feedlot, yet there are few monetary rewards for making that extra effort.

He has tested more than 3,000 head over the years looking for consistency and predictability.

Even the unique colour pattern of black or red dappled on a white hide is analyzed.

The cattle produce spotted cattle, straight white with black ears, muzzle and feet or straight black.

The colour pattern became a problem for some cattle producers who preferred more traditional colours. However, some Americans in the pre-BSE days approached them for show steers because the cattle were different and performed well in carcass competitions.

The herd of 100 cows traces back to a single dappled heifer with unknown parentage named Liz. Raines’s father saw the blue-black symmetrical colouration on white and decided the female was likely a Shorthorn-Holstein cross.

When Liz was bred to an Angus bull, the same spotted pattern appeared. The resulting calves exhibited better than average beef qualities and the family decided to pursue this unusual breeding. The cattle are similar in type to Speckle Park, an emerging breed developed in Saskatchewan that has gained a reputation for high carcass quality.