This is the time of year when I prepare to teach the University of Calgary’s second year veterinary students about bone diseases. One could make all sorts of arguments about why bones are important for animal health and are an interesting system to study. But it really boils down to this: as Dr. Andy Allen put it when he was teaching my class this topic, you need to know a disease exists in order to diagnose it.

Although not the most exciting body system to study — who isn’t fascinated by the workings of the heart and how it pumps blood through all tubes to the rest of the body? — bones are the body’s foundation. They provide rigid structure to the body of animals, protecting vital organs such as the brain, heart and lungs. Bones are also the site of muscle and ligament attachment, giving the body the mechanical leverage needed for motion. Minerals such as calcium are stored in bones and can be pulled out of these reservoirs in times of need. Finally, bones are home to marrow, the critical tissue that gives rise to white and red blood cells.

Read Also

Foot-and-mouth disease planning must account for wildlife

Our country’s classification as FMD-free by the World Organization for Animal Health has significant and important implications for accessing foreign markets.

I start the students off with a discussion of broken bones. Fractures arise from high-force trauma to healthy bones but bones can also break when they are fundamentally unhealthy. We call this latter type pathological fractures. For example, infection or a tumour weakens the bone, making it prone to fracture.

From there we move on to bone diseases that arise from abnormal metabolism, including poor nutrition. Starved animals use up fat reservoirs; the last of these to go is bone marrow fat.

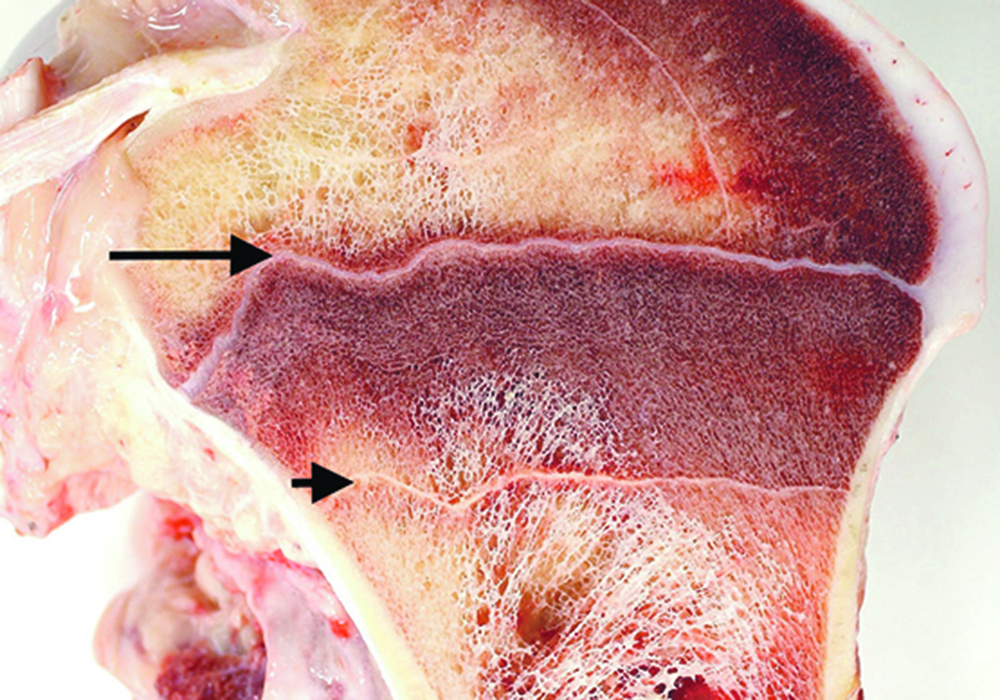

Bone marrow that lacks fat becomes pink and watery in a process called serous atrophy of fat. Imagine the last soup bone you cooked. The fat in that was likely a healthy, off-white, firm fat we expect to see in healthy animals. Animal diets that are poor in calcium and vitamin D and high in phosphorus can create bone abnormalities that are especially evident in growing animals. An example of this is rickets, which leads to severely enlarged growth plates.

We spend time discussing bone infections. Viruses don’t usually directly infect bones. But when they cause disease in growing animals, they leave tell-tail lines near the growth plate. Viruses infect the cells responsible for bone remodelling, which stops while the animal is sick, creating a line. When the bone is cut, these lines are an indication that a virus infection occurred in the weeks to months prior. This is what we see in calves with bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) infection.

Bacteria and fungi can directly infect bones. These germs can be introduced through wounds or travel to bones in the blood. Growth plates of growing animals are a hot spot for bacterial infections.

I wrap up this teaching section by discussing a few rare congenital bone diseases. For example, fatal marble bone disease (osteopetrosis) is a genetic disease that occurs in some Angus cattle. Bones don’t remodel properly during growth. This manifests as short bones that don’t have proper space for bone marrow. Skull bones don’t grow properly either, leading to brain abnormalities and compression of the optic nerves that convey information from the eyes to the brain (and back). These cattle not only look funny, but they are also blind and die shortly after birth. Luckily, the genetic defect is known and can be tested for to eliminate from herds.

These genetic diseases are rare and unlikely to impact the average farm animal, but they give us interesting insight into how bones grow and develop. It is often through disease, when something goes horribly wrong, that we find out the details of what is supposed to happen in health.

Dr. Jamie Rothenburger, DVM, MVetSc,PhD, DACVP, is a veterinarian who practices pathology and is an assistant professor at the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. Twitter: @JRothenburger