Less than 20 percent of Alberta calves may have registered birth dates, which then requires other verification methods

HANNA, Alta. — Age verification is required for all Alberta cattle born since 2009, but few people record their animals’ birth dates.

“It is common to have fewer than 20 percent of Alberta calves age verified,” said Ryan Kasko, vice-president of the Alberta Cattle Feeders Association.

“What the Alberta cattle feeders want is age identified with the tags.”

The animal’s birth date is linked to the Canadian Cattle Identification Agency radio frequency identification ear tag number. These numbers are then linked to a database called the Canadian Livestock Tracking System.

Read Also

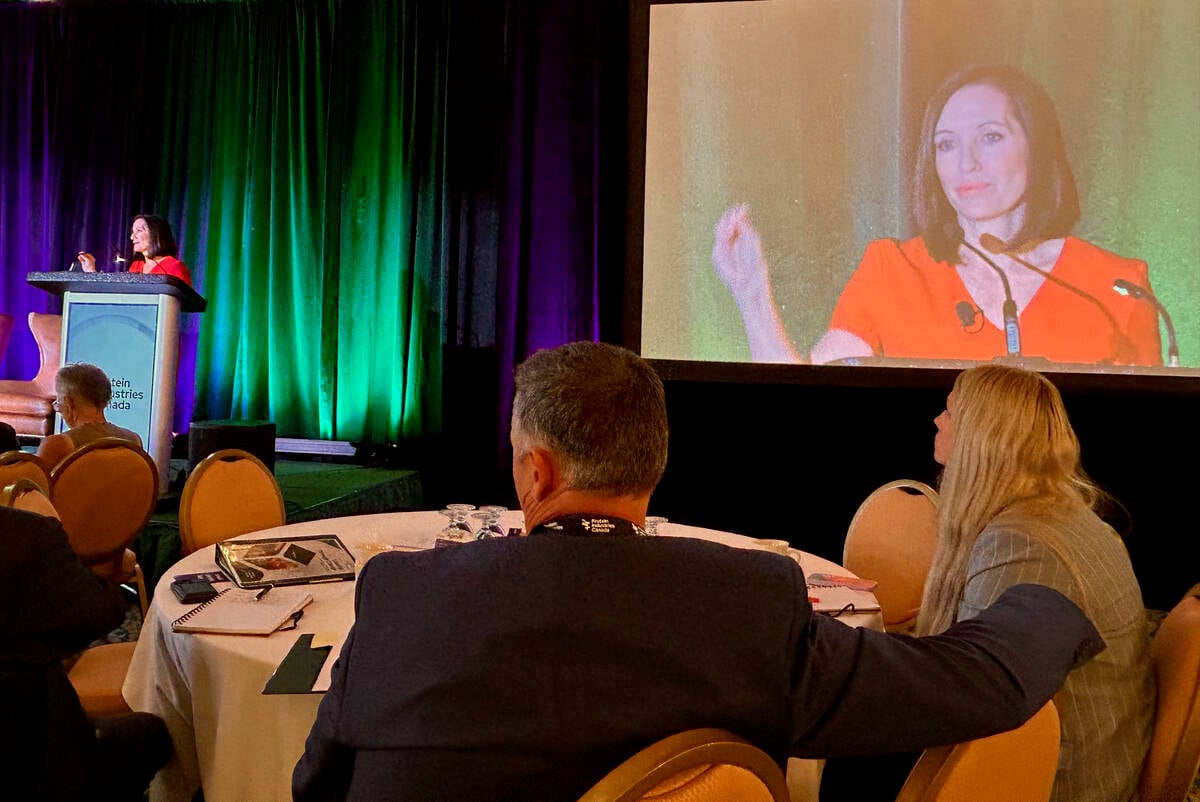

Canada told trade crisis solutions in its hands

Canadians and Canadian exporters need to accept that the old rules of trade are over, and open access to the U.S. market may also be over, says the chief financial correspondent for CTV News.

In addition, Alberta feedlots with 1,000 head or more are required to scan cattle when they enter the property and the numbers are forwarded to the agency. Having a birth date attached is useful for marketing cattle because it eliminates any doubt as to whether the animal is younger than 30 months, said Kasko who is also head of Kasko Cattle Co. at Coaldale.

If there is no birth date, the processor checks to see how many permanent teeth have erupted. This indicates the animal is maturing and is not eligible for export to markets like Japan because it is too old. As well specified risk materials thought to vectors for BSE spread, must be destroyed. The carcass is also discounted and for a company dealing in thousands of animals, that can add up.

Some cattle show up without tags so the feedlot replaces them. Another problem is wrong information attached to the tags.

A batch of tags may have been registered and leftovers are used the following year but the birth dates were not changed.

“When they get to our feedlot it will show that animal was born two years ago and when they go to the packing plant we get discounted,” he said.

If a few are obviously wrong, the feedlot may contact the identification agency to track the animals back to the producer to correct the age.

“We want people to take a little extra time to make sure that if they are putting a tag in the animal’s ear it is the correct birth date,” he said.

With fears over BSE, Japan demanded beef derived from cattle younger than 20 months of age until a few years ago. It now accepts younger than 30 months.

“For the good of the industry we want to have good accurate information so our trading partners can recognize it,” Kasko said.

While age verification is a legal requirement the government is not enforcing it, said Rick Frederickson of Alberta Agriculture at a recent traceability workshop held in Hanna.

“We have not been enforcing it provincially. We have a requirement and regulation but we have chosen to try to communicate the need and the value as opposed to enforcing and ticketing people,” he said.

“The result is we don’t have everybody participating and in some cases there are questions from producers about whether anybody cares,” he said.

Calves are supposed to be age verified either by the actual birth date or according to calving dates before they are 10 months of age or before they leave the farm, whichever comes first.

Some consider it a value attribute but it is also useful when doing disease surveillance. The world animal health organization oversees BSE status and requires testing of a certain number of animals within the older age group. This information can provide the right ones for testing to show the disease is under control.

Producers are also expected to hold on to records for 10 years.

“Our experience with some of the BSE cases that we’ve had makes it difficult to go that far back without records,” Frederickson said.

“Having the on-farm records to support an investigation is critical,” he said.

Alberta offers services to help with tagging or adding information to the identification agency database. Call 877-909-2333 or 310 FARM for information.

barbara.duckworth@producer.com