There comes a time, usually in middle age, when a person wishes they had paid more attention to their parents’ and grandparents’ stories. It was no different for Pete Standing Alone, who thought the dances, ceremonies and traditions on his southern Alberta Blood Reserve were dull and unimportant.

“I was just a spectator. I thought these things were for the old folks. I didn’t know then how completely my mind would change,” said Standing Alone in the 1982 National Film Board film Standing Alone.

He recognizes that young people on the reserve know very little about the customs and traditions of their ancestors, and it was his desire to pass down those traditions.

Read Also

Fuel rebate rule change will affect taxes and AgriStability

The federal government recently announced updates to the fuel rebates that farmers have been receiving since 2019-20.

Throughout his youth, Standing Alone worked on oil rigs in the United States before coming back to the reserve to raise horses and his family.

“I used to be a wild kid. Drank anything, chased around, took a lot of chances.”

But his parents died in a car crash, friends and family died and Standing Alone knew he needed to come home and teach his children and other members of the community about their history. In a dream, Standing Alone understood he should raise true Indian horses, a fast, fine-boned horse with great endurance, like the horses his great-grandfather rode and raised.

“My father was a cowboy, my great-grandfather a buffalo hunter.”

Back on the reserve, Standing Alone taught himself how to make saddles and carve intricate designs into the leather. In 1977, one of his saddles was gifted, along with a horse, to then Prince Charles on the 100th anniversary of Treaty 7. Standing Alone eventually built a herd of more than 200 horses.

On the north end of the reserve, on land not broken by farming, is a stone circle with four directions marked in stone. Some say the teepee circle is from a chief who died there. When the cairn was partially opened by archeologist’s the arrow and spear points found in the cairn dated back 5,000 years.

“For 5,000 years or more our people lived here with nature. I can not imagine such a span of time.”

Standing Alone was a friend of the filmmaker, Colin Low, and the rest of the Low family. The Low family grew up on the Cochrane Ranch, near Waterton National Park, where Ged, Colin’s father, was ranch manager. The Cochrane Ranch was renamed the Church Ranch and is now the Palmer Ranch.

When Ged Low was ranch manager, each time he drove to town he would pick up anyone walking on the road and befriend them, said Stephen Low, Colin’s son and Ged’s grandson.

“My grandfather was a great socialist. He was friends with everybody. Almost every trip we took to town he would stop to pick up First Nations. He would never fail to stop. If there were five of them on the side of the road or 10, it didn’t matter. They all piled into the truck,” said Low, who became a filmmaker just like his father, Colin.

Stephen Low still has a small piece of land with a house along the nearby Belly River near the original ranch.

Through their time in southern Alberta, the Low family knew all the “great characters” in the area. The cowboy in Colin Low’s 1954 film Corral was one of the ranch hands on the Cochrane Ranch.

“He knew these characters through his upbringing,” Stephen said of his father’s connections.

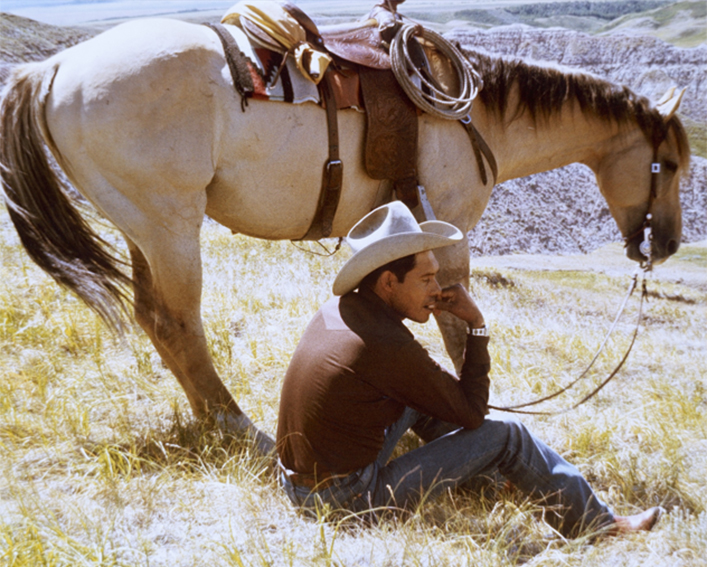

“Pete Standing Alone was a super nice guy, a real gentleman. He was handsome and tall. He was a key character in the film.”

At the time, the National Film Board’s mandate was to celebrate the “unusual, unheard, unstudied cultures of Canada.” Low’s father’s films Corral, The Hutterites, Standing Alone, Circle of the Sun and others were unique insights into often hidden cultures. Colin Low directed more than 50 NFB documentaries from Fogo Island off the coast of Newfoundland to the Prairies.

“These films are unique insights into these cultures. Colin would go into the reserve and see things differently. He could see their own struggles with the young there. The struggles they have to remember the past and yet deal with the reality of the present, which is the most important thing as the world changes,” said Stephen, who lives in Montreal.

Low said his father likely spent a year thinking about the film, scouting locations, developing the script and talking to the community about filming before getting the NFB to finance and approve the project. Because so much time was spent in the community, the Low family developed deep friendships with many of the film’s subjects, including Standing Alone.

“He was a real, real close family friend,” said Stephen.

“When Standing Alone came to Montreal for business or other projects, he would stay with the family.”

Standing Alone went on to be a member of the Blood Band Council for six years, helping to bring economic development projects to the community, including a housing factory and a potato business.

This column is part of a year-long collaboration between The Western Producer and the National Film Board of Canada celebrating the newspaper’s 100th anniversary.