A member of a First Nations band carries on the three-generation tradition of incorporating reserve land into family farm

About half the land Garan Rewerts farms is on First Nations land, carrying on a tradition passed down from his father and grandfather.

Rewerts doesn’t know exactly when his paternal grandfather started farming land on First Nation reserves near their Cut Knife, Sask., farm, but believes it may have been in the 1980s. His father, Robert, later took over that tradition.

“As I took over the farm, some of the arrangements just kept going, and then we just expanded as land came available. I know the band seemed interested in having me farm it and rent it,” said Rewerts, a band member of the Poundmaker Cree Nation.

Read Also

Producer profits remain under significant pressure

Manitoba farmers are facing down a double hit of high input costs, like fertilizer, and low grain prices as they harvest their next crop.

His mother, Sandra, and maternal grandfather are Poundmaker members.

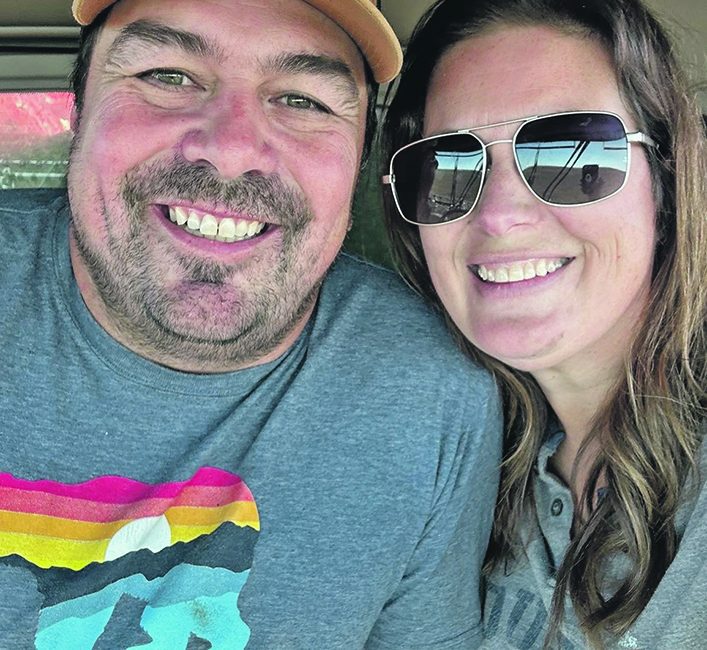

Rewerts and his wife, Aaron, also farm land on Sweetgrass First Nation near Gallivan, Sask., Little Pine First Nation near Cutknife, Sask., and Poundmaker’s Treaty Entitlement Land near Wilkie, Sask. Between First Nations land, their family’s land and other rented land, the farm is scattered across 100 kilometres.

“You have to keep a really close track,” he said.

“I try to simplify it. On one reserve, I’ll seed all the same crop so at least I know what I have on those land locations or in an area. It is a lot easier now with mapping and GPS.”

On his rented land at Poundmaker Reserve, Rewerts seeded just canola. Next year it will likely be all wheat.

Unlike non-reserve land, most First Nation land was not surveyed or divided into one mile sections by the Dominion Land Survey system in the late 1800s. Land can be all one large chunk of land or small 10 to 15 acre sections.

“For crop insurance and hail insurance it is a bit more work. I have lots of land locations with 12 or 15 acres on it, and you really have to keep close track of that,” said Rewerts, who rents land from the band or individual band members, depending on the situation.

Because there is no traditional surveyed land on the reserves, there are no roads bordering the fields and few maintained roads.

“There’s not really any infrastructure. It’s not surveyed, so there’s no roads on the mile like off the reserve. So there are goat trails and some rough land you haul across. Because it’s all rented land, there’s no storage out there so we use temporary storage like grain bags, or haul it off.”

Add in wandering livestock damaging grain bags, and Rewerts prefers to haul all the grain off the reserve.

“There’s lots of animals roaming around: cows and horses sometimes and different trails on the land. You just have to learn to live with it. If you’re going to stress about stuff like that, it’s probably not a good spot for you to farm.”

Despite some of the hassles, Rewerts said the reserve land is some of the most scenic land he farms with fields bordered by trees, coulees, creeks and rivers.

“It is just beautiful out there. The landscape is hilly with lots of valleys and wildlife,” said Rewerts, who grew up on the family farm near Cut Knife but also spent time on the Poundmaker reserve as a child.

Revert’s maternal grandfather, Henry Savel, a band member and chief, farmed at Poundmaker on the band farm. Like most farms at the time, it was mixed grain and livestock. While there are fewer large First Nation farmers, many traditional farming families still live on the reserves.

Just like off the reserve, rental agreements are not permanent and are at risk of being lost, but Rewerts has plans to continue farming the land as long as possible.

His children have shown interest in farming. The oldest son, Nolan, works in nearby Unity and his daughters, Graycen and Addison, both study agriculture at the University of Saskatchewan. The youngest son, Dane, still in high school, helps out on the farm driving machinery.

“I hope they will be involved in the farm somehow.”