Land rolling is a typically overlooked agricultural practice for most growers.

Farmers roll to flatten dirt and rocks to protect equipment during silage or harvest production, without much thought toward agronomics.

The technology and thought process is a simple one, but how does the timing of land rolling affect the crop’s performance?

Read Also

U.S. bill could keep out Canadian truckers

The Protecting America’s Roads Act, which was tabled in the U.S. House of Representatives at the beginning of October, would “rid the country of illegal immigrant commercial truck drivers and ineligible foreign nationals.”

Carlo Van Herk, field operations lead at the Farming Smarter Association in Lethbridge, supervised research on the best time to roll cereal crops.

“It started with a conversation with an agronomist who said that his clients, or his farmers, were rolling their cereal crops at any point throughout the season,” said Van Herk.

“He was interested in what was the best time to roll because he’s seen some damage sometimes with late rolling or some compaction issues with early rolling.”

With funding from Alberta’s Results Driven Agriculture Research (RDAR), testing sites were set up at Lethbridge, Bow Island, Stirling and Barons. Three sites were set up each year, and trials were conducted from 2022-2024 on barley and soft wheat.

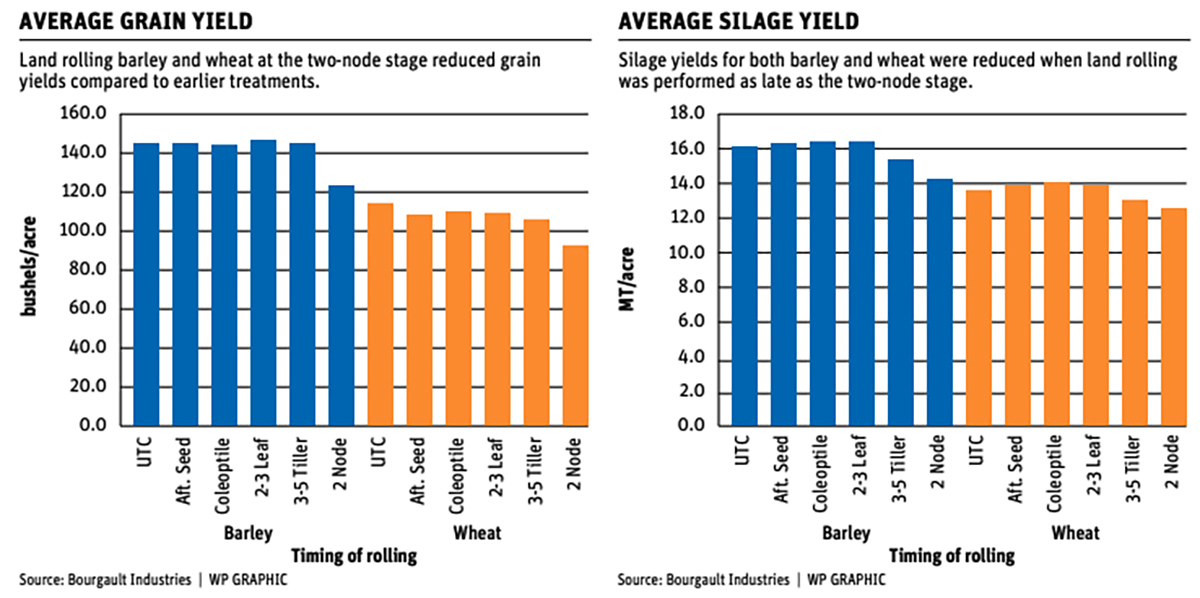

The land rolling was done at different stages of the growth cycle. Plots were rolled directly after seeding until the two-node stage to see which timing produced the highest yields and proficiency.

“As soon as we started entering the late tillering stage of cereal crop, we start to see either decreases in yield or increases in disease presence,” said Van Herk.

Ergot was increasingly prevalent when crops were rolled late, with crimping damage and shorter height also a result. Nearly 20 bushels per acre in grain yield and two tonnes per acre in silage yield are lost when rolling at the two-node stage.

When rolled after seeding until the three-leaf stage, there was nearly no difference in grain or silage yield and no difference in disease pressure, but soil compaction can vary at these stages.

“If you look at compaction, we see slightly more compaction on the early rolled compared to the late rolled (cereals).… It basically boils down to rolling at that three-leaf stage or the early tillering for both maintaining a good yield while getting the full impact or the full advantages of rolling without compacting your soil too much.”

Soil compaction can influence plant height by preventing normal root development, potentially restricting the uptake of nutrients and lowering plant height and yield.

However, timely rain can loosen the soil enough to minimize the potential damage to the crop, so growers may choose to roll directly behind the seeder as long as the dirt is dry. When wet, compaction can become too great.

As for rolling during the three leaf to tillering stage, it may be ideal for yield, disease and soil compaction, but there is the threat of damaging the crop with equipment.

The trials were performed by rolling the plots in a straight line, while farmers turning their tractors and rollers in the field could potentially damage plants that have rooted, compared to seeds that were just planted.

However, rolling in the three-leaf stage can make a difference in cereal crop yields as long as equipment damage can be minimized.