The western Canadian agricultural industry saw a brutal year in 2021. It was frustrating to have record prices for grain and then have Mother Nature turn on us and not provide the wherewithal to produce crops to take advantage of them.

With many crops yielding much below half of what is considered average in any area, salt was rubbed into farmers’ wounds when they had to buy out contracts they had signed at attractive prices, but were unable to deliver.

I have been asked several times this fall to describe how to accurately predict yields to try and avoid a repeat of last year’s circumstances. Because so much of the factors that go into yield are the result of Mother Nature’s graces — good and bad, predicting yield is next to impossible. However, there are things you can do, using averages, that may enable you to get a better picture of what to expect next year.

When predicting next year’s yields, one thing to avoid is using your best year as a target. Sure, you had a great crop in 2016, but things lined up that year. There was good spring moisture and great subsoil moisture, the temperature was warm but not overly hot, and every time you thought you could use a shot of rain, down it came. So that 60 bushel canola was an exception and not the rule.

Even though your seed representative tells you the hybrid he sold you will outyield the one you grew in 2016, what makes you think you will grow more?

Don’t use what your neighbour tells you he grew in 2016 either.

When trying to predict a yield for the upcoming year, I think back to something a professor said almost 50 years ago when I was sitting in a soil fertility class. We were discussing Liebig’s Law of the Minimum.

“In Western Canada water is our most limiting nutrient.” I wrote a column discussing this law in 2019. Liebig’s law of the minimum, often simply called Liebig’s law or the law of the minimum, is a principle developed in agricultural science by the German scientist Carl Sprengel (1840) and later popularized by Justus von Liebig.

It states that growth and yield are dictated not by total resources available, but by the scarcest resource, often called the limiting factor. Often this principle is used by retailers and marketing persons to indicate that by bringing all your nutrients up to a certain level, you will be able to maximize the genetic potential of your variety or hybrid. In a perfect world this may occur.

However, we saw what happens when there is not enough water. It really doesn’t matter how much N,P,K or S or a full cart of micronutrient groceries you throw at a crop. The yield was determined in 2020 and 2021 in most areas by how much moisture your crop had.

I’m going to compare the process of estimating your yield target to preparing a budget for your lending agency to apply for an operating loan.

So, step one is to estimate how much cash you have in the bank. This can be equated to estimating your yield is to determine how much moisture you have in your soil this fall.

To do this, we have to measure how far the moisture has gone into the soil. By measuring this depth and determining the texture of the soil, we can estimate the amount of water in the soil.

Soil scientists have measured this for us and prepared a table that estimates the amount of water available in 30 centimetres (one foot) of soil.

Step two is like a deposit that is made in the spring. It is to estimate how much moisture you believe you will receive from snow melt.

This can be tricky because all stubble and all snow are not created equal. For example, many experts estimate that there is about a 10:1 ratio when estimating the water content of snow. 30 cm of snow will yield three cm of water. Therefore, if you have a wheat stubble that is 30 cm high and it is full of snow, you have about three cm of water.

Whether this water soaks into the soil will depend on the soil texture, the slope of the topography and if the soil is frozen or not. Taller stubble will hold more snow and shorter will hold less.

Step three is an estimate on how much income you will have during the growing season, or an estimate of how much rain you will get through the key growing months of May, June and July.

If you are growing soybeans and corn, add in August. Here, we can look at 30-year averages provided for a number of locations across Western Canada by Environment Canada.

The use of past averages are more accurate than long-term forecasts. Don’t try to over-think this by researching rainfall in an El Niño year or what the probability of getting above normal rainfall following two years of drought. Use the averages. They are our best-guess of what to expect next year.

There are too many complicating factors that impact these numbers. For example, a study done at Agriculture Canada in Swift Current found that a 2.1 bu. increase in wheat yields resulted from 2.5 cm of rain occurring in May where it only resulted in 1.3 bu. if it fell in June and a whopping 3.1 bu. from July rains. So just use the averages.

Step four is the addition of all the moisture that we expect to occur from freeze up in the fall till the end of July (or August). This equates to tabulating your estimated account balance. Adding the three moisture sources will give you an idea as to how much water you have to grow a crop.

Step 5 will be the calculation of how much crop can be produced for the available moisture. We do this by referring to the Moisture Use Efficiency (MUE) chart that is included. While these numbers are 15 years old, for the most part, they are probably still accurate. However, with the advancements in canola hybrids, this number may be 10 percent conservative.

The final step is to put this information together. Let’s take a couple of examples to explain.

Example 1. You are a farmer in the Hodgeville district in the Palliser Plains of southwest Saskatchewan. Your soil is a fine sandy loam and you have measured 20 cm average of moisture in the soil this fall. From the above table, we can estimate that there are from 2.5 – 3.3 cm of available water going into the fall. This field was in durum in 2021 but the stubble was cut at 7.5 cm high. Due to this fact and because a lot of snowfall and melt events occurred in the area, we are going to add 1.25 to 2.5cm of moisture.

Next, we look at average rainfall for Hodgeville. From an internet search, I see that, on average, Hodgeville receives 51.7 millimetres of rain in May, 44.9 mm in June and 42.4 mm in July.

Now we can total things up. If we are aggressive and add 3.3 + 2.5 + 5.17 + 4.49 + 4.24 we get a total available moisture to grow a crop of 19.7 cm.

Our Hodgeville farmer is planning to seed peas, and from the above chart, we see that we can achieve 3.25 bu. per 2.5 cm of available moisture. A quick calculation tells us that there would be, on average, enough moisture to grow a 25 to 26 bu. pea crop.

Using the same calculations and ignoring the fact that durum was grown last year, assuming averages, there would be enough moisture to grow 31 to 32 bu. of wheat.

Taking this calculation to another area, we have a farmer west of Melfort, Sask., with silty clay loam soil.

He received fall rain and measured 60 cm of moisture this fall.

His silty clay loam soil is expected to be holding nine to 10 cm of available moisture. He was able to cut his crop at about 30 cm this fall. This would probably capture 2.5 cm of moisture.

Finally, on average, 55 mm of rain can be expected in May, 94 mm in June and 102 mm in July.

Adding these numbers together, we calculate that on average, this farm can expect 376 mm of moisture.

If this producer is planting canola, he could expect a 60 bu. crop or if he plants wheat, 67 to 68 bu.

This is not an exact science because we are using averages, but the results of this exercise will allow you to make an educated guess as to what your yield might be.

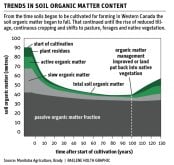

Other factors such as varieties/hybrids grown and tillage and fertilizing practices may impact these numbers. For example, we know using no-till practices improves MUE as does banding rather than broadcasting fertilizer.

Coming up with an accurate yield forecast is a valuable asset to your farm enterprise. It also allows for adjustments to nitrogen inputs based on your target yield and it allows you to make better decisions when forward pricing crops for the 2022 season.

Thom Weir PAg is a certified crop advisor and professional agrologist in the Yorkton, Sask., region. You can reach him at thom.weir@farmersedge.ca.