Millions of acres of tile drainage in the U.S. Midwest have contributed to a 15,000 sq. kilometre dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, says a U.S. professor.

Mark David, a natural resources professor at the University of Illinois, said tiles are a source of soluble nitrates, which enter the Mississippi River and eventually dump an excessive amount of nutrients into the Gulf of Mexico.

Once in the gulf, the nutrients consume most of the oxygen in the water, leading to a condition called hypoxia that kills aquatic life.

Read Also

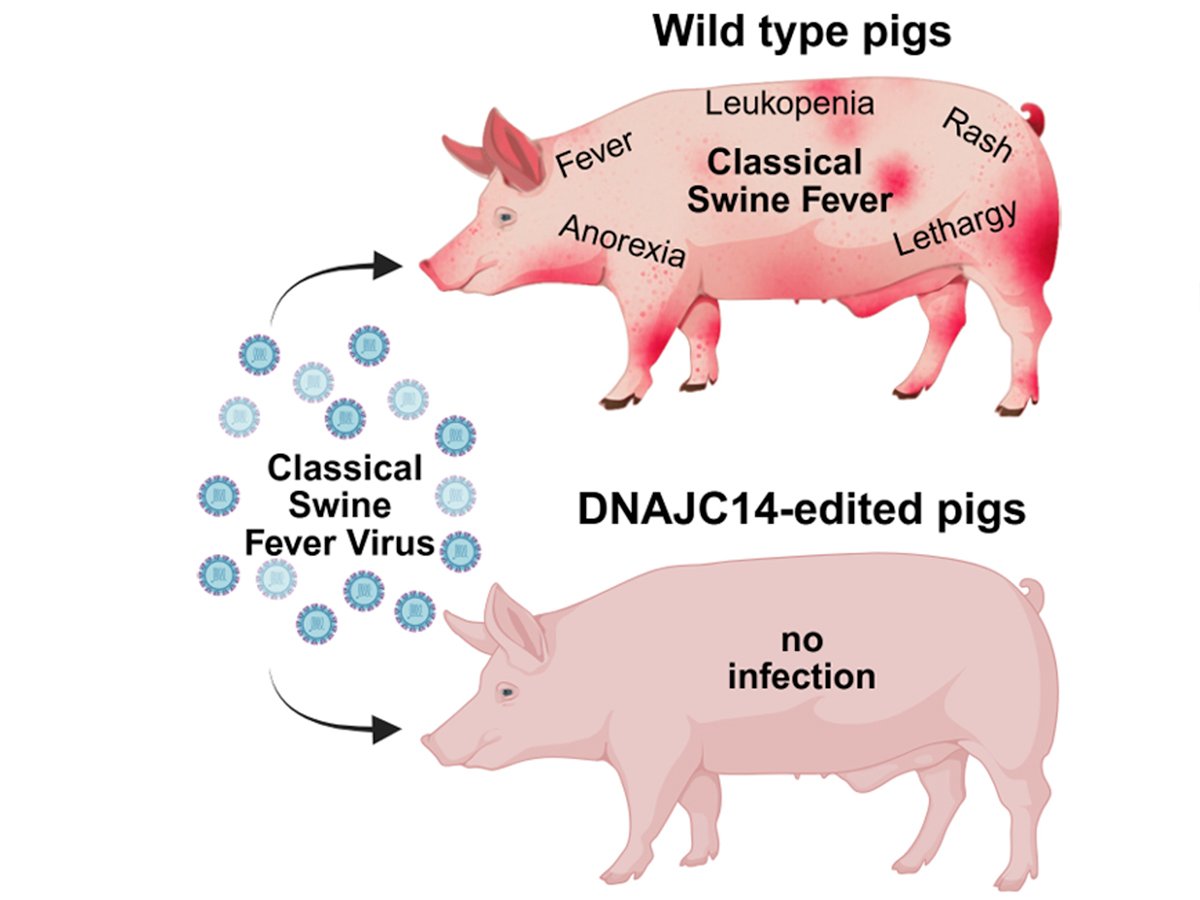

Gene edited pig resistant to classical swine fever

British scientists have discovered a gene edit that could provide resistance to classical swine fever in pigs and Bovine Viral Diarrhea in cattle

David attempted to get a better handle on how nitrogen enters the gulf by calculating all the nitrogen inputs and outputs from each county in the Mississippi River basin from 1997 to 2006.

He concluded that tile drainage isn’t the only environmental villain in this story. Rather, it’s part of a leaky agricultural system in the United States that permits nitrates to flow rapidly into streams, rivers and oceans.

“Tile drains don’t automatically mean that you’re going to lose nitrates,” said David, whose study, Sources of Nitrate Yields in the Mississippi River Basin, was published last fall in theJournal of Environmental Quality.

“But there’s no doubt that tile drainage, because it’s moving the water so well, if you have any nitrate in there, it can move with (the water).”

He said ripping out tile drainage isn’t an option, but producers will need to adopt beneficial management practices to reduce the amount of nitrates coming from tiled fields:

• timing of fertilizer applications;

• applying some fertilizer during spring seeding and side dressing as needed after planting;

• incorporating a cover crop into the rotation;

• constructing a small wetland at the end of the pipe.

However, David said someone will have to pay for those improvements.

“All those things can work but they cost money,” he said.

“If we want to reduce nitrate, we’re going to have to help farmers do it…. So maybe provide some (financial) incentive… to help minimize the nitrate loss.”