Growers forced by disease to eschew peas and lentils have options to stay productive while the threat abates

It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but pulse producers across the Prairies have come to expect it.

If there is aphanomyces root rot in a field where peas, lentils or other susceptible pulses are grown, there is little choice but to rotate crops without those pulses until the disease is gone. That can take six to 10 years, say experts.

“It’s basically just a waiting game for those (aphanomyces) oospores to die off,” said Syama Chatterton, a plant pathologist with the Agriculture Canada research centre in Lethbridge.

The rotation itself doesn’t kill the disease but absence of susceptible crops prevents soil inoculum levels from building, wrote Meagen Reed, agronomy manager with Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, in an email.

There are a few things producers can do to keep soil healthy while nature is doing its work, such as including non-susceptible, nitrogen-fixing pulse crops in rotations.

Planting crops that encourage pea growth once a field is free of disease is another, and faithful record-keeping can prevent the disease in the first place.

It may be cold comfort, but an upside to dry conditions of the past several years is that they’re not conducive to new aphanomyces taking hold.

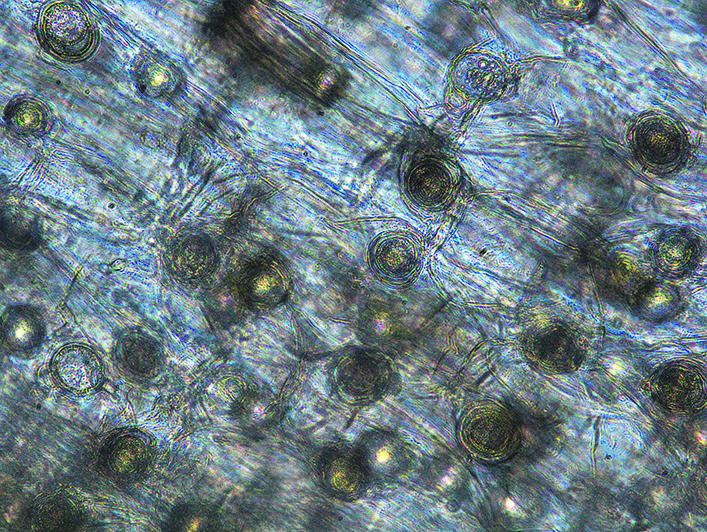

Aphanomyces euteiches is a water mould that germinates in high moisture soils. It produces resting spores called oospores, which have thick cell walls that allow them to survive in soil for a long time.

“It makes them resistant to the environmental degradation that we often see can occur with other microorganisms,” said Chatterton.

The disease’s effects are compounded by its tendency to occur in a complex with pathogens such as fusarium, pythium and rhizoctonia, said Reed.

Chatterton and other researchers have been working to develop tools that can accurately measure oospore levels, but it’s been a battle.

“I’ve been doing that research for the past I think five or six years. But it’s been difficult to get an accurate quantification so it’s difficult to know how long it’s actually taking and when it’s safe to put a pea or lentil back into that field,” Chatterton said.

Some chemical seed treatments suppress the disease but they’re not a great fit, though they do provide early-season suppression.

“The issue is that we often see aphanomyces come in later in the season. It’s not usually at the seedling stage, which is what a seed treatment would protect. Usually it comes in after we get a good rainfall in June.”

The key to fighting the disease is making sure it doesn’t happen in the first place, said Jennifer McCombe-Theroux, a production specialist with Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers.

This comes down to record-keeping and not planting peas, lentils and other susceptible crops in conditions where the disease thrives.

“So it’s just really choosing the right field that doesn’t have much standing water and then just having a minimum of a one in four-year start,” she said.

“And then always evaluating the suitability of the field to pulse crops. Does it have higher clay content, poor drainage, compaction – just some of those things to really think about when you’re planting pulses.”

If a field has aphanomyces, take susceptible pulses out of the rotation and consider what conditions were like when the infected crop was planted, said McCombe-Theroux.

“If it was a wet year with heavier rot pressure, that oospore load would be quite high and a longer rotation break would be needed. If it was a very high degree of disease pressure, it could be 10 years. If the moisture conditions were reasonable and disease pressure was low, a minimum break of six years could also be considered.”

Producers shouldn’t consider their work done once they get to the end of this rotation break, said Reed.

“If a field has confirmed aphanomyces, you can avoid growing peas or lentils there for eight to 10 years, and if in the 10th year moisture conditions are conducive to oospore germination, an aphanomyces infection can still occur.”

Reed has a list of non-susceptible or resistant pulses that can also help prevent an infection, including chickpeas, faba beans, some varieties of dry beans, soybeans and fenugreek.

Chickpeas, faba beans and soybeans can also fix nitrogen in the absence of peas and lentils, although they aren’t as dependable as peas in this role.

“Peas can grow anywhere on the Prairies, whereas faba beans need moisture, chickpeas need drier conditions and soybeans need a longer growing season,” said Chatterton.

She urged cover crop growers to be mindful about legumes in the mix.

“If you’re a producer interested in cover crops, pay attention to some of those other legume hosts because there are things like vetches that can also be a host,” she said.

Chatterton is not aware of any crops that can speed the degradation of oocytes, but some may lay a groundwork once peas can be safely reintroduced.

Some researchers suggest oats as a good rotational crop to reduce oospores faster. Chatterton, Robyne Bowness and the University of Saskatchewan tested the idea with a crop sequence trial.

They were unable to verify that oats can help eliminate oospores, but they did find a preceding oat or faba bean crop seemed to boost pea yields in the following year.

“We planted a pea crop as a way of determining if disease pressure had diminished. There was a yield increase in the pea crops planted after faba bean and oat crops compared to the pea crop planted after a pea or wheat crop at the Lacombe location,” said Chatterton.

“So oats and faba bean can be beneficial crops to include in a rotation to help mitigate aphanomyces in the long term, but a lengthy rotation away from pea will still be needed.”

How long it takes will vary by location, said Chatterton.

“We’re recommending six to eight years but in some fields, we’ve observed that it can be longer than that.”

The reverse can also be true.

“In some fields with the work we’ve been doing in Lacombe, we’ve seen fields recover fairly quickly within six years. But in some of the trial areas that we have close to Lethbridge (they’ve) been upwards of eight years now and we haven’t seen a recovery.”

Lethbridge is in the dark brown soil zone, while Lacombe is in the black soil zone. Soil zone might play a role, but warrants further investigation.

“In the black soil zone, they don’t usually have higher organic matter (but) maybe higher microbial activity, so you may be getting breakdown on those oospores longer,” said Chatterton.

“And maybe down here in Lethbridge where we’ve had a lot more drought and drier soil conditions, the microbes to break down those oospores probably aren’t as active.”