Len Hingley, an irrigation specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation, urges irrigators to consider proper rates based on soil media.

“Rate is the amount of water that we apply at or below the infiltration rate of our soils, and it is driven by texture,” he said.

Sand tops the list of soil particle sizes at 0.05 to two millimetres. It’s visible to the eye. In comparison, a particle of clay is less than 0.002 mm.

Read Also

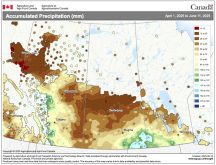

Manitoba Parkland research station grapples with dry year

Drought conditions in northwestern Manitoba have forced researchers at the Parkland Crop Diversification Foundation to terminate some projects and reseed others.

“That cannot be seen with the unaided eye,” Hingley said. “You might need a microscope or something to see clay. Silt, you might be able to see it.”

When it comes to water infiltration of those different soils, “a sandy soil can take in 30 mm an hour or more of water at any one point in time, and clay is only able to take one to five mm per hour,” he said.

Sandy loam typically infiltrates at around 25 mm an hour.

If there’s already enough moisture to fill the soil profile, some will be lost to deep percolation. Water will seep from the rooting zone and into the water table. Deep percolation can occur in all soil types.

Soil with higher clay content has more risk of loss above the soil surface. Clay loam tends toward ponding and runoff if application rates miss the mark. In those cases, there’s risk of creating a hypoxic soil condition, wherein soil is so full of water that there’s no room for air.

Translated to management decisions, producers may want to speed the pivot over low spots in fields to avoid overly wet areas where water accumulates.

Irrigation volume calculations should focus on the soil’s carrying capacity, said Hingley.

Clay soils have more tightly packed plates, limiting infiltration, but the structure of clay soils also creates more pore space.

“As a result of the structure that we currently have, we’re able to hold more water within that soil profile, as opposed to the sandy soil which allows the water to flow through.”

Loam sand holds an estimated 112 mm within a one-metre profile, while clay holds 192 mm per metre. Silty clay loam holds 220 mm, the highest amount of any soil type.

Clay is also reluctant to release water, Hingley said.

“That available water holding capacity is the difference between field capacity and permanent wilting point.”

Field capacity is when water is applied, or there is a rainfall event of two to three inches, which starts to fill the soil profile.

“Permanent wilting point is the point at which our plants can no longer extract water from that profile,” he said. “The difference between the two is our available crop water. That available crop water is what we’re looking for.

“We want to make sure we target that. We want to make sure we don’t dip into our permanent wilting point.”

Producers should also be familiar with how much water plants use so they can optimize amount and generate the best yields. This can be done by monitoring evapotranspiration, which measures both evaporation and transpiration.

“Evaporation is the water released from soil and plant surfaces as well as open water,” said Hingley. “Transpiration is the amount of water that comes out of your plant leaves and out through the stomata under the leaf.”

Evapotranspiration can be accelerated by high temperatures, increased sunlight and stronger winds. Higher humidity decreases evapotranspiration.