The Leaf-Evaluated-Nutrient System from Picketa Systems provides immediate analysis for 13 nutrients

Glacier FarmMedia – A nutrient testing system first used in potatoes is now moving into corn.

The Leaf-Evaluated-Nutrient System (LENS) unit from Picketa Systems, based in Fredericton, N.B., is promising growers and crop advisers a new, efficient and cost-effective testing method for nutrients.

The technology has been used in potato crops for the past three growing seasons, and the company expanded its network of testers and added sites in the United Kingdom in 2023.

The company hopes to eventually adapt the technology for other crops commonly grown in Manitoba.

Company literature shares a well-known flaw in nutrient efficiency; roughly 50 per cent of nitrogen-based fertilizer applied to crops is used by the plant and the remainder is lost to the environment.

In the past, over-application of nutrients has been accepted as a necessary cost, given that under-applying leads to poorer yields. Although fertilizer prices have come down in the past two years, land and equipment prices and the cost of the federal government’s price on carbon have prompted many growers to seek tools to ensure the highest nutrient efficiency.

The science behind LENS technology is called chemometrics and uses the reflectance of plant tissue across a wide spectral range as an input to machine-learning algorithms.

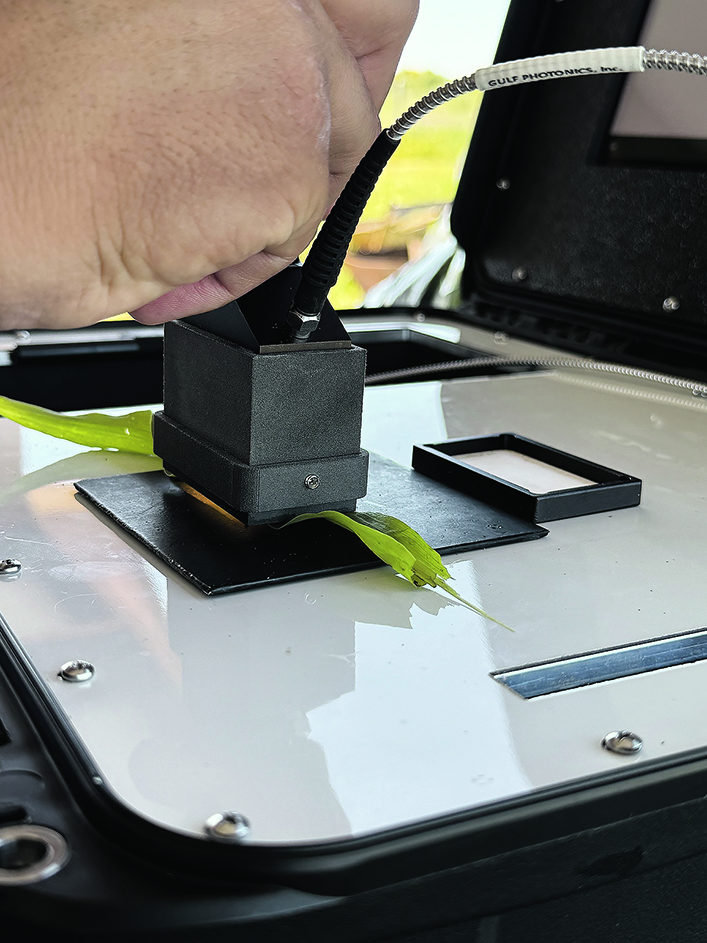

A tester gathers 10 to 15 samples from an area of the field — leaves that are free of visible damage and disease — and scans each leaf with the LENS probe. The click of a button submits the sample. The results are almost instantaneous.

“The whole point was to have a system that could give you agronomic feedback in the field,” says Xavier Hébert-Couturier, co-founder and chief executive officer of Picketa Systems.

“And not just for nitrogen, but for 13 different nutrients, with ratings for nitrogen, nitrate nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus, all the way to micronutrients like calcium, boron, manganese and magnesium. They’re all the ones you’d get from a typical lab test and that’s what we’re trying to offer in a different way.”

Accuracy of the system is encouraging, based on results from the past three years with potatoes, in which the average error was less than two to three per cent for N, P and K compared to laboratory results.

For micronutrients, accuracy was six to eight per cent error on average but Hébert-Couturier said that could be due to contamination from fungicide applications —for magnesium in particular — or differences in calibrations relative to a lab test.

The company has seen good results in tests in corn conducted in New Brunswick during summer 2023. This past winter, a unit was taken to Chile, where the company further calibrated LENS for corn.

For 2024, it expects to work across 10 sites in the U.S. Midwest and in California, where it’s also being used in potatoes. There are plans to move the LENS technology into canola, soybeans, cereals and eventually all crops.

Picketa has tested the LENS unit in different growth stages in corn, at V2 through to tassel. In potatoes, agronomists and crop advisers tested every week or once every two weeks, although that crop is more intensively managed.

“What we’ve heard in talking to farmers is that if you have it, you’re going to use it right before an application, maybe the day of,” says Hébert-Couturier.

“Then you’re waiting five to seven days after to determine the uptake. We’ve seen people being able to take more data points but typically, they’re planning on using it two or three key times during the season.”

Speed of results allows quick decisions on spray applications and with more-than-adequate accuracy. With conventional lab testing, plant samples can begin decomposing before they reach a lab, leading to inaccurate analyses.

Although the LENS unit is simple to operate, most current users are agronomists, researchers and retailers — the people who scout and assess crop health and timing for applications.

In 2023, some of those who used the testing unit took more than 1,500 samples.

“It’s for those businesses that have the dedicated staff and the trucks that are serving 20 or 30 farmers,” says Hébert-Couturier.

“It’s not the farmer who has to go out and learn this new system and takes the samples, it’s for the agronomist who can fit it into their workflow that they’re already used to sending off samples to the lab.”