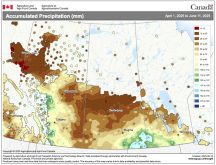

Although it’s too early to tell for sure, trusted sources are suggesting drought conditions on the horizon for 2024.

According to Agriculture Canada’s Canadian Drought Monitor in its December 2023 drought assessment, 100 percent of the prairie region at month-end was classified as abnormally dry or in moderate to exceptional drought. This includes all of the region’s agricultural landscape.

So what does that mean for prairie pulse producers making decisions on what to plant this spring? Three specialists — one each from Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan — weigh in.

Read Also

More work wanted on removing red tape

REGINA — Canadian farmers risk falling further behind competitors if two main federal agencies don’t become more efficient and responsive…

Manitoba

Three of the biggest pulses grown by acreage in Manitoba include field peas, dry beans and soybeans, says Dennis Lange, pulse and soybean specialist with Manitoba Agriculture.

All three can be managed in dry conditions but peas have a bit of an edge. Their frost tolerance sometimes allows them to be planted as early as April, presumably giving them a head start before the heat of summer begins.

Peas can also be planted as deep as three inches, giving them good access to moisture, Lange says.

“If you have to go down a bit deeper to get moisture, those peas will push through that deeper soil as they germinate at a little lower temperature,” he says.

“They do perform well. I’ve seen peas come up from those three inches without too much difficulty just because of the nature of the plant.”

Although field peas can be a good fit, Lange doesn’t think any one pulse is necessarily better than another when it comes to dry year performance. Ultimately, they all need their own individual management and timely rains.

“Having good seed moisture at seeding time will get the crop off to a good start, and then having a little drier (conditions) will help the crops root down, whether they’re peas, beans or soybeans,” he says.

Alberta

Ask Robyne Davidson for the best pulses to plant under dry conditions in Alberta and she’ll tell you field peas and lentils are growers’ best bets. However, they should pay attention to their soil zone suitability, says the pulse specialist with Lakeland College.

Lentils tend to do well in the dark grey soils of the Peace country as well as the brown and lighter brown soils in southern Alberta east to the Saskatchewan border. However, be wary if you’re planting them in the black soils of some of the province’s central areas.

“As soon as you put lentils into central Alberta, where we have the heavier black soils, lentils don’t do well at all,” she says.

“If the area of the province you’re growing your crop in is not suited to lentils in general, don’t take the risk. If we get a significant rainfall the lentils will be severely set back.”

Davidson generally recommends planting red lentils over greens for a number of agronomic and market reasons. Although greens tend to capture a higher price, it’s also a niche market that’s more difficult to sell into, she says.

Fababeans are a crop Davidson strongly discourages Alberta producers from planting when under the threat of drought.

“If we’re anticipating a drought this year across the province, I would say don’t put fababeans in,” she says.

“They’re a fantastic crop. They do wonderful things with available moisture. But in dry conditions they are very poor-yielding.”

Saskatchewan

In Saskatchewan, the brown and dark brown soil zones tend to be the driest of the dry in drought conditions.

Dale Risula, a specialist with Saskatchewan’s agriculture ministry, also champions lentils for their drought suitability. However, growers need to be mindful when choosing a specific lentil to grow.

“It looks to me like there’s a lot of small red lentils that probably do the best in drier areas,” he says.

“So I’m expecting that a lot of growers will probably be growing reds. That’s been the case over the last number of years anyhow.”

Although not quite as adaptable to dry conditions as lentils, chickpeas are another good pulse choice for Saskatchewan if there’s a strong possibility of drought, says Risula.

“They have a taproot that goes down to about a metre or so, so they can take advantage of any moisture that might be deeper in the soil profile,” he says.

If there’s one upside to dry conditions, it’s that many crop diseases don’t get a chance to establish. However, the infamous aphanomyces root rot might be a wild card.

The soil-borne disease is a water mould that infects plants by travelling through free water in the soil. In other words, the less moisture there is in the soil, the less likely it is to spread.

But that doesn’t mean it can’t be a threat in dry years. For one thing, it also travels by wind and soil movement and tends to stay in the soil for years. For another, its travelling companion tends to be fusarium, a fungal disease that is also soil-borne.

“The problem with aphanomyces is that fusarium and aphanomyces travel together,” says Davidson.

“Fusarium is much more generalistic; it attacks everything. Aphanomyces is specific to the pulse crops that it attacks, like lentils and peas.

“Aphanomyces is very soil-borne. It’s kind of like the clubroot of pulses. And there’s potentially really high spore loads in your soils.

“So to say that aphanomyces is not an issue at all in a dry year is not quite accurate because if you’re moving soil around, you’re moving spores around.”

There are few chemical treatments for aphanomyces at this point, but producers can minimize its threat by routinely cleaning equipment and — in the bigger picture — adjusting rotations.

“Choosing fields that you know have been away from peas for a minimum of six years is what we’re recommending right now,” says Davidson.

“Keep an eye on those fields. If you have a pea field that looks really sick and really bad all across the board, stay out of peas for longer than six years.”

Risula agrees that the impact of aphanomyces is felt more in wet years than dry, but he still urges vigilance.

He recommends standard good farming practices to get a jump on the disease. Some of these include seeding into areas with minimal likelihood of being infected, extending rotations and selecting varieties with high germination potential.

“Seed treatments are probably a good idea just to ward off any other organisms that might be impacting your plants as they germinate. Fertilize to the best of plant requirements for pulses; that would be mostly phosphorus.”